Today in South Asian history: the First Battle of Panipat (1526)

Babur conquers northern India and establishes the Mughal Empire.

If you’re interested in history and foreign affairs, Foreign Exchanges is the newsletter for you! Sign up for free today for regular updates on international news and US foreign policy, delivered straight to your email inbox, or subscribe and unlock the full FX experience:

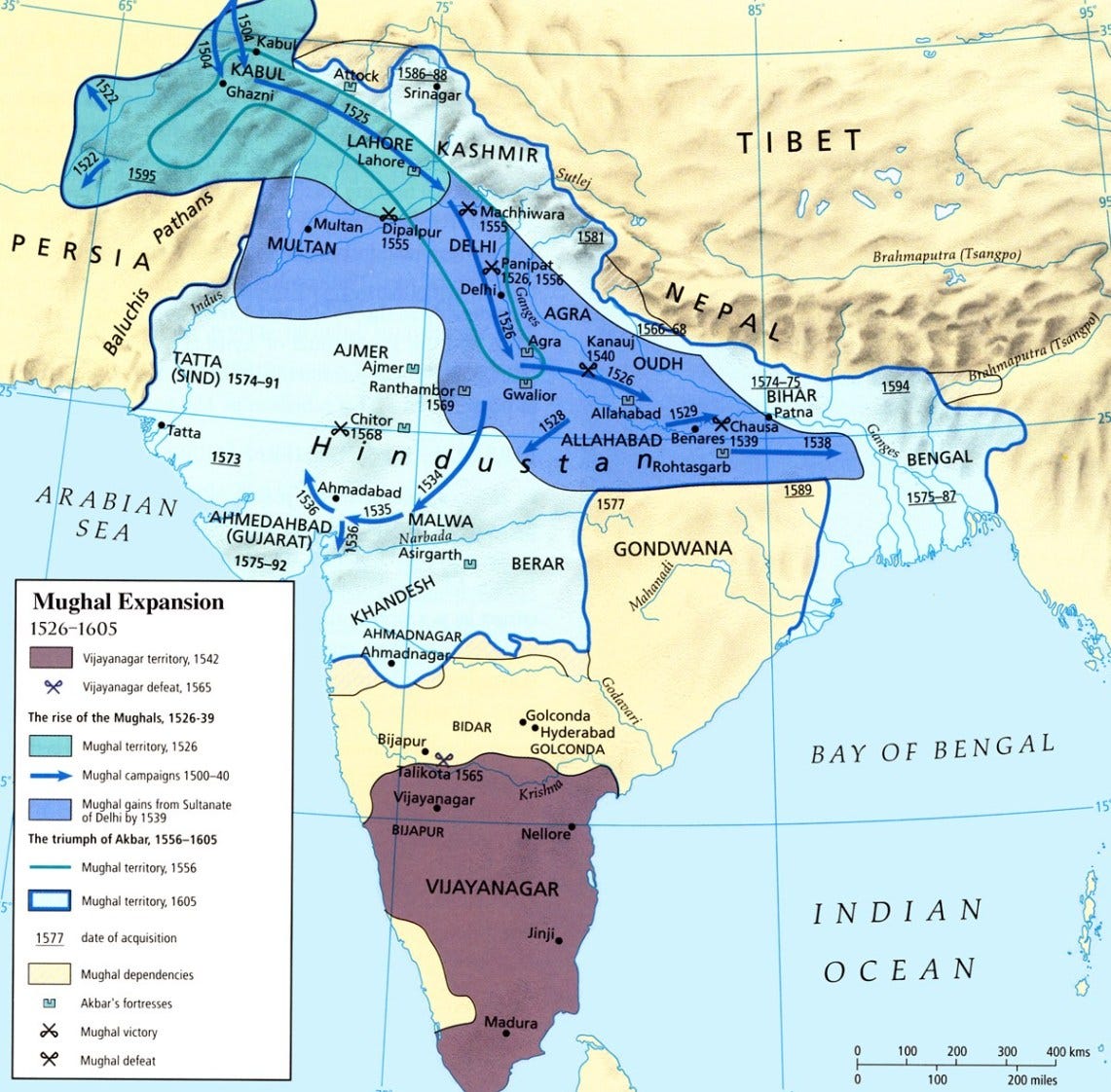

As the title indicates, and as regular readers will already know, today’s anniversary isn’t the only major battle that Panipat has seen over the past few centuries. I don’t think I’m doing the other two battles a disservice if I say that this first one was the most significant of the three, because it led to the establishment of the Mughal Empire. With the exception of a brief interlude from 1540 to 1555, it would remain a fixture in northern India, in one form or another, until the 19th century. While no empire is born overnight, it is to Panipat in 1526 when most historians date the beginnings of this empire, one of the most important in Islamic history and South Asian history. The battle also happens to be a pretty stark example of the potency of 16th century gunpowder weapons, which allowed a heavily outnumbered Mughal army (estimated around 12,000 men) to pretty easily defeat the army of the Delhi Sultanate (which various estimates put somewhere between 50,000 and 100,000 strong).

The Mughals were commanded by their founder, Babur (d. 1530), who was heir to a very illustrious tradition of Central Asian conquerors but, ironically, had decided to march over the Hindu Kush into India in part because he was tired of getting his ass kicked regularly in Central Asia.

Babur, whose real name was Zahir al-Din Muhammad, was a descendant of both Timur, on his father’s side, and Genghis Khan, on his mother’s side, so he had the bloodlines of a conqueror for sure. Timur’s empire had shattered in the decades since his death in 1405, so when Babur became the ruler of the city of Ferghana (in modern Uzbekistan) in 1495 (at the age of 11) he was only one of many Timurid princes controlling a small piece of what had once been a pretty vast empire. But as Timur had dreamed of restoring the empire of Genghis Khan, so Babur had designs on rebuilding his ancestor’s empire, and he set his sights on conquering Timur’s old capital, Samarkand. He captured it in 1497…then promptly lost Ferghana to a rebellion and immediately lost Samarkand when he left to try to put down the rebellion in Ferghana. He tried again to take Samarkand in 1501, but was defeated by the new power in Central Asia, the Uzbeks under Muhammad Shaybani (d. 1510). Not a terribly auspicious start to a would-be career of conquest.

Now without a home base, Babur and his army spent some time as guests of one of his uncles in Tashkent before, in 1504, crossing over the Hindu Kush and capturing Kabul. He was still bound and determined to conquer Central Asia, and viewed India, to his south, as merely a convenient place to do a little raiding when he needed resources. And when the Uzbeks conquered Herat in 1507, Babur was probably the last Timurid prince left standing, so if anybody was going to put the family business back together it would have to be him.

Eventually Babur cut a deal with the Safavids in Iran, under which he accepted Safavid suzerainty in return for their help defeating the Uzbeks and installing him in Samarkand. This seemed like a pretty decent plan. The Safavids had crushed the Uzbeks at Merv in 1510 and killed their ruler, Muhammad Shaybani (Safavid Shah Ismail I famously had his skull turned into a fancy goblet, which must have been a real conversation starter). But in 1512 at the Battle of Ghijduwan, with Babur and his followers fighting alongside them, the internal tensions that would plague the Safavids over the next couple of centuries came to the surface and the Uzbeks won a surprising victory. Finally Babur had to face the facts: his plans for Central Asia were bust. If he was going to be a great conqueror, his conquests would have to come elsewhere. Specifically, in India.

Northern India had been ruled since the early 13th century by a series of dynasties that get lumped together by historians as the “Delhi Sultanate.” This is misleading, since it implies more continuity than was actually the case. It’s even more misleading when you learn that Delhi wasn’t always the capital of the sultanate—in 1526, for example, the capital was Agra. The sultanate at this point was ruled by the Lodi dynasty, a Pashtun family that had taken over the kingdom in 1451. They were ruled by Ibrahim Lodi (d. 1526, and yes that’s a spoiler). Ibrahim doesn’t seem to have been much of a ruler, and Babur was actually invited to invade Lodi territory around 1524 by other members of the Lodi clan who were afraid that the sultanate was about to break apart.

Panipat has been a popular location for major set-piece battles over the centuries, because it’s well-positioned on the main road south from the Hindu Kush into India proper. It was here where Ibrahim attempted to snuff out Babur’s much smaller army through sheer numbers. Unfortunately for him, Babur evidently had enough advance warning of the Lodi army’s advance on Panipat that he was able to prepare by roping carts together to form a battlefield fortification that his gunners, firing both field artillery and matchlocks, could use for cover. This “wagon fort” was a tactic the Ottomans used to great effect, one they’d adopted from Europeans in the 15th century. Alongside the wagon fort, Babur dug trenches to protect his flanks.

Babur also chose an area where Ibrahim would have to narrow his line in order to advance, which left the Lodi army vulnerable to attack on both of its flanks. It doesn’t seem like there was very much to the battle–basically, Babur had guns and Ibrahim didn’t, and that combined with a well-timed flanking movement was more than enough to overcome the Lodis’ manpower advantage. Ibrahim did have war elephants, which had always been pretty devastating in battle, but not only were they rendered ineffective by Babur’s preparations, but it seems they were startled by the gunfire into trampling their own men. Ibrahim died along with roughly 15000 of his men, and the Lodi Dynasty was no more.

One of the great things about Babur is that he’s the rare pre-modern historical figure who actually wrote an authentic autobiography (as opposed to having a phony autobiography attributed to him later on, a disturbingly common recurrence), which we call the Baburnama (“the book of Babur”). It is not only a very useful source (bearing in mind that the author is a little biased) but is also remarkably plain-spoken and readable for something written in the 1500s (it was translated into English by Wheeler Thackston if you’re interested in picking up a copy). So for most of the major events of his life, and several minor ones, we can actually read Babur’s own description. Here’s part of what he writes about the Battle of Panipat:

The sun was one lance high when battle was enjoined. The fighting continued until midday. At noon the enemy was overcome and vanquished to the delight of our friends. By God’s grace and generosity such a difficult action was made easy for us, and such a numerous army was ground into the dust in half a day. Five or six thousand men were killed in one place near Ibrahim. All told, the dead of this battle were estimated at between fifteen and sixteen thousand. Later, when we came to Agra, we learned from reports [DWD NOTE: these were likely exaggerated] that forty to fifty thousand men had died in the battle. With the enemy defeated and felled, we proceeded.

After the battle the Mughals occupied first Delhi and then Agra, which became Babur’s new capital. The next year, Babur defeated another much larger force, this time belonging to the Hindu Rajput Confederation, at Khanwa, which showed that the new Mughal Empire was clearly not going anywhere. And it didn’t…until Babur’s son, Humayun, lost the whole empire in 1540, that is. But Humayun got it back (with Safavid help) in 1555, his son Akbar won the Second Battle of Panipat in 1556, and the Mughal hold over northern India was pretty stable for the next couple of centuries.