Today in Middle Eastern history: Saladin takes Jerusalem (1187)

The great triumph of the First Crusade is reversed as Jerusalem returns to Muslim control.

If you’re interested in history and foreign affairs, Foreign Exchanges is the newsletter for you! Sign up for free today for regular updates on international news and US foreign policy, delivered straight to your email inbox, or subscribe and unlock the full FX experience:

There are plenty of things wrong with Ridley Scott’s 2005 Crusades epic Kingdom of Heaven. It completely rewrites the history of the court at Jerusalem, for one thing. In Scott’s story, Princess (later queen) Sybilla (d. 1190) is trapped in an unhappy marriage to malicious idiot (and later king) Guy of Lusignon (d. 1194), leading her to have a fling with a young, righteous, but agnostic court outsider, Balian of Ibelin (d. 1193). In reality, Sybilla seems to have been at least content with her marriage, and it’s not clear that Guy was any more malicious than your average 12th century ambitious noble, though the idiot part seems about right. Scott’s hero, Balian, really was the hero of the siege of Jerusalem from the Christian side, but he was decidedly middle aged, wasn’t agnostic, definitely wasn’t an outsider, and didn’t have a fling with Sybilla. Unless you see the director’s cut, the young and very ill-fated King Baldwin V never appears in the film at all, which is historically inaccurate and makes some of the characters’ choices seem inexplicable.

I could go on, but I’m not a movie critic.

There is one scene towards the end of the film that I do like. After Saladin’s (d. 1193) army has battered Jerusalem for a few days—even knocking down one of its walls—but hasn’t been able to take the city, Balian rides out to parley with him. Balian warns that if Saladin refuses to allow every Christian inside the city safe passage out of Muslim territory, he will order the city’s defenders to destroy Jerusalem itself before they make a final stand, which he promises will “break” Saladin’s army. Part of the reason I like this scene is because it is actually pretty close to how we’re told the real conversation between Balian and Saladin actually played out. The very well-renowned Arab historian Ibn al-Athir (d. 1233), who was actually in Saladin’s retinue and witnessed the siege firsthand, wrote that Balian told Saladin1:

O sultan, be aware that this city holds a mass of people so great that God alone knows their number. They now hesitate to continue the fight, because they hope that you will spare their lives as you have spared so many others, because they love life and hate death. But if we see that death is inevitable, then, by God, we will kill our own women and children and burn all that we possess. We will not leave you a single dinar of booty, not a single dirham, not a single man or woman to lead into captivity. Then we shall destroy the sacred rock, Al-Aqsa mosque, and many other sites; we will kill the five thousand Muslim prisoners we now hold, and we will exterminate the mounts and all the beasts. In the end, we will come outside the city, and we will fight against you as one fights for one’s life. Not one of us will die without having killed several of you!

OK, so this is a little different from the film, where Balian never says anything about killing women and children and says that he and his knights will destroy all the holy places in the city, not just the Muslim holy places. Regardless, this threat was enough to get Saladin to agree to stop fighting and, with one important condition, to give the people in Jerusalem safe passage. He agreed partly because this was a threat the Christians could probably have carried out and partly because safe passage in exchange for surrendering the city was the deal Saladin had offered the defenders before the siege began. At that point, the Crusaders rejected his offer, so then he swore to take the city by force. But Balian was able to talk him back down basically to his original offer. One thing the movie doesn’t mention is that Saladin’s offer of safe passage was contingent upon the payment of ransom, and those who couldn’t pay, well, they didn’t get to leave.

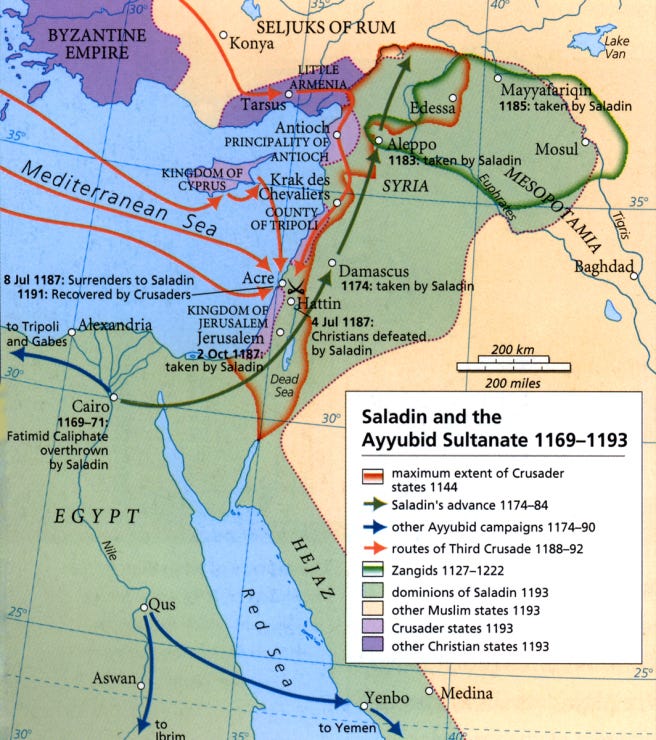

There’s not a whole lot to say about the Siege of Jerusalem itself. The city’s fate was sealed months earlier at the Battle of Hattin, when its army was virtually wiped out in the single most devastating defeat the Crusaders ever suffered. After Hattin, Saladin’s army scooped up Acre and then Ascalon before setting its sights on the main prize, Jerusalem, which it besieged on September 20.

While regular readers will know that I don’t generally have very nice things to say about the Crusaders, there is a certain something about the defense of Jerusalem, carried out mostly by common citizens and squires—some of whom were knighted by Balian out of a desperate need for manpower—that I think you have to respect. These weren’t the putzes who rode out to their destruction at Hattin, they were people who had been abandoned by those putzes. The fact that they managed to hold out for even 12 days against Saladin’s much larger (20,000 men against maybe 5,000 defenders), much better equipped, much better trained army is a testament first to the challenges of medieval siege warfare (Jerusalem, with its strong walls and effective control over its own water supply, was a tough target for any besieging army), but also to the will and determination of its defenders. Yes, we could say that they made a mistake not jumping on Saladin’s original offer of a peaceful surrender, but let’s not discount the fact that a) they may not have trusted Saladin to keep his word and b) these were genuinely religious people who may have had difficulty abandoning “Christ’s city” to the Muslims without at least putting up a fight.

Contrary to the film, Balian and Saladin actually knew each other before they met outside the walls of Jerusalem. After Hattin, Balian fled to Tyre, and while he was there he asked Saladin for permission to retrieve his wife—Maria Comnena, the widow of former King Amalric I (d. 1174)—from Jerusalem. Saladin agreed in return for Balian’s promise not to raise arms against him. But when Balian got to the city, the leaderless inhabitants begged him to stay and organize the defense, so Balian went to Saladin again and asked to be released from his promise. Balian must have asked nicely, because not only did Saladin agree, but he had Balian’s wife, their children, and their household servants all safely taken out of Jerusalem and delivered to Tripoli.

Saladin’s army bashed itself against the walls for almost 10 days but was unable to get past them, despite having brought massive siege machinery with it. In the meantime, it suffered considerably higher casualties than the defenders. On September 29, Saladin had part of the wall mined and then sent his army into the breach, but the opposing sides fought to a stalemate. However, by this point the Crusader numbers were dwindling and there was no hope of reinforcement. When Balian rode out for his parley with Saladin, with clergy and women engaged in communal prayer throughout Jerusalem, he was simply out of men to defend the city. I don’t want to say that Balian was bluffing Saladin, because even the diminished Christian garrison could have trashed the city and the Islamic holy sites while Saladin watched helplessly from afar, but if the Muslims had managed to collapse another section of the wall it seems doubtful that Balian and his men could have fought them off again.

As I said above, the Hollywood ending that the defeated Christians were all given “safe passage” out of Muslim lands belies the reality that they had to pay for that safe passage, at the price of 10 dinars a piece. This was a sum that many simply couldn’t meet, and as many as 15,000 inhabitants of the city were sold into slavery. But many of the siege’s wealthier participants made some efforts to free those who couldn’t afford their own ransom. Balian was able to arrange a 30,000 dinar ransom for about 7000 of them, for example (I guess he got a bulk discount). Saladin’s brother, al-Adil, asked for and was gifted 1000 Christian slaves whom he immediately liberated. The Latin Patriarch of Jerusalem, Heraclius (d. ~1191) then requested a group of slaves to liberate and was given 700, while Balian was given 500 for the same purpose. Saladin released the aged, along with another 1000 Christians who were supposedly from the city of Edessa (modern Urfa), the birthplace of one of Saladin’s men.

The Grand Masters of the Hospitaller and Templar orders were forced by public outrage to donate some funds to ransom additional captives. Still, we’re told that Heraclius and the two Grand Masters left the city carrying enough loot that they could have probably ransomed the remaining Christian captives as well. Christians who were already native to Jerusalem (mostly Orthodox and Syrian Christians) were allowed to stay and were left untouched, and Christian pilgrims were allowed to freely enter the city. In Europe, plans for another Crusade had already gotten underway after word of Hattin reached Rome, but the loss of Jerusalem sped things up, and by 1189 a new group of Crusaders was forming to try to take Jerusalem back from Saladin. They failed, but not for lack of trying.

Amin Maalouf, The Crusades Through Arab Eyes (Schocken: 1989), p. 198

Just watched Kingdom of Heaven the director's cut the other night. I much prefer the real story, thanks for posting