Today in Central Asian history: the Mongols take Samarkand (1220)

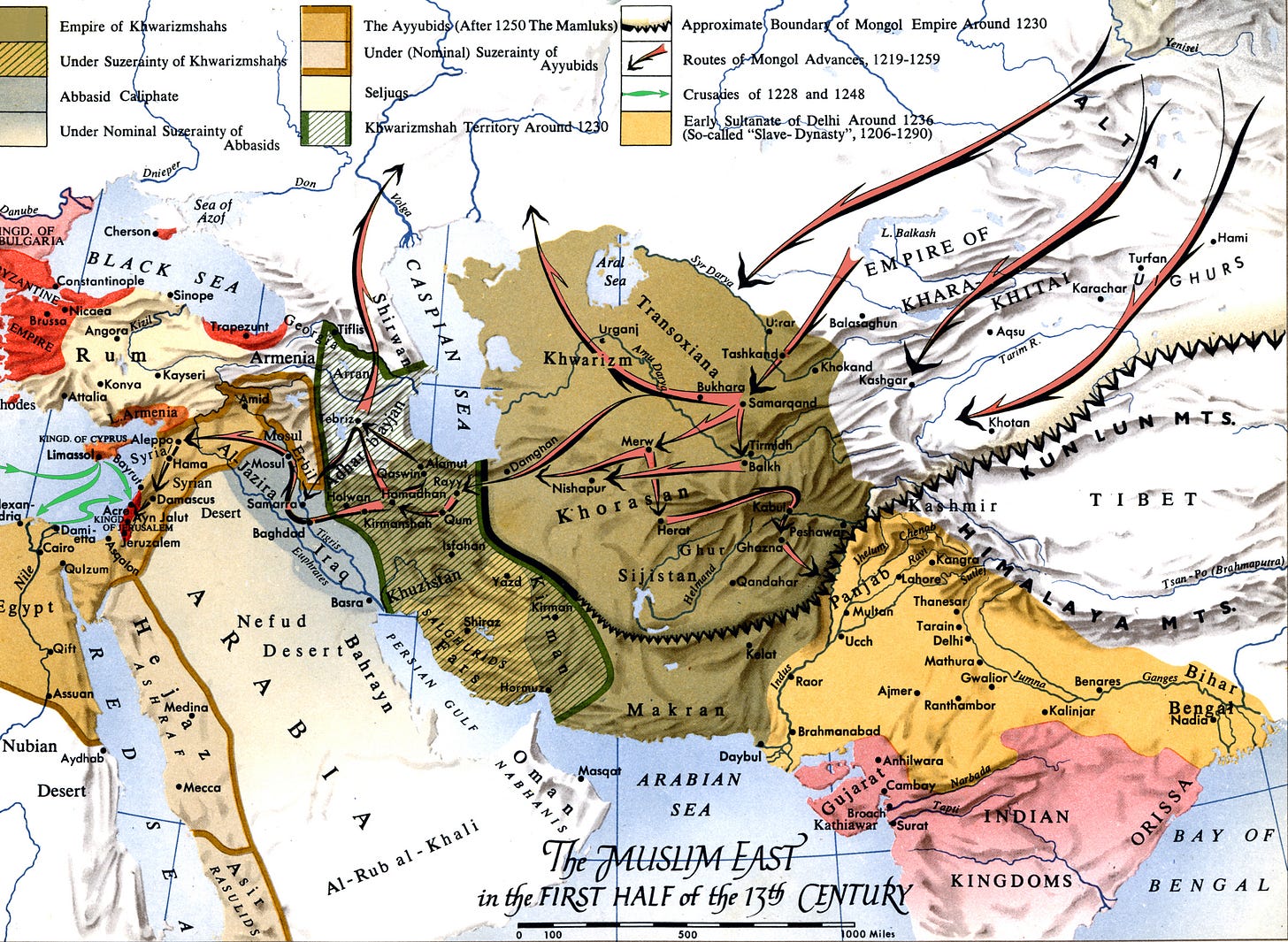

Genghis Khan's invasion of Central Asia results in his conquest of the Khwarazmian Empire.

If you’re interested in history and foreign affairs, Foreign Exchanges is the newsletter for you! Sign up for free today for regular updates on international news and US foreign policy, delivered straight to your email inbox, or subscribe and unlock the full FX experience:

The Mongol conquest of the city of Samarkand is, like many of Genghis Khan’s western conquests, kind of anticlimactic. For a number of reasons that we’ll get into shortly, the polity that ruled most of Central Asia at this time, the Khwarazmian Empire, was unprepared and poorly led which made it fairly easy pickings for the Mongols. The former is somewhat understandable—nobody outside of the eastern steppes and northern China was really prepared for the Mongols in 1220 because in many ways they were unprecedented—but the latter made for some pretty inexplicable decisions that hastened the empire’s collapse. But even though this siege isn’t terribly dramatic, it does give us a chance to talk about the Mongols in their salad days so let’s give it a go.

There were a few events that I could have chosen on which to hang a discussion of Genghis Khan’s Central Asian campaign. We could, for example, have talked about the siege and sacking of Otrar, which was the Mongol’s first target because its governor had executed their envoys (we’ll get to that), or Genghis Khan’s lightning annihilation of Bukhara, which immediately preceded his move against Samarkand. I’ve picked this siege because Samarkand was at the time the capital of the Khwarazmian Empire and its loss sent the empire’s ruler, Shah Muhammad II, into a panicked flight whence he would never return. Also, unlike those other two candidates we actually have a date for the fall of Samarkand: March 19, courtesy of Persian/Indian historian Minhaj-i Siraj Juzjani (d. after 1266). It might not be the right date—other sources offer alternatives. But those other options make less sense in the overall context of the Mongolian campaign than March 19, and anyway this is my newsletter so I get to decide.

When the Mongolian warlord Temüjin became became the acknowledged ruler of the eastern steppe peoples under the regal title “Genghis Khan” in 1206, he turned his attention first to the Xi Xia kingdom of northwestern China and then to the Jin kingdom in northern China. By 1215 his army had captured the Jin capital of Zhongdu, forcing the dynasty to shift its court to the city of Kaifeng in the lower Yellow River valley. Not long after, Genghis Khan dispatched a relatively small force (two tumans, or around 20,000 men) west under one of his senior generals, Jebe, to wipe out the Qara Khitai (or “Western Liao” if you prefer) kingdom which was centered around modern-day Kyrgyzstan. The Qara Khitai rulers had seen their throne usurped by a man named Kuchlug, who was a member of the Naiman people of the eastern steppe. He’d escaped the Mongol conquest of the Naiman back in 1204, escaped them again in 1208, and the Mongols seem to have worried that he might come back looking for vengeance. So they struck first, with Jebe’s army chasing Kuchlug to the city of Kashgar (in the modern Xinjiang region of China) and killing him in 1218.

This campaign against the Qara Khitai must have brought the Mongols to Shah Muhammad II’s attention. The Khwarazmian Empire had formerly been a vassal of the Qara Khitai before emerging as an independent entity in the late 12th century, and there are indications that the shah had his own designs on conquering the remnants of the Qara Khitai and maybe even continuing on into China. He likely viewed the Mongols as both a threat to his kingdom as it was and as an obstacle standing in the way of growing his kingdom into what he’d have liked it to be. So it’s very possible that he was itching for a fight.

On the Mongol side, however, we really have no indication that there was any intent to advance beyond the Qara Khitai region—at least not in the short-term. And that makes sense, because presumably the first item on Genghis Khan’s agenda would have been completing his conquest of the Jin. In the meantime, like all nomadic peoples the Mongols were almost as interested in doing business as they were in making war, so they assembled what appears to have been a pretty substantial commercial caravan and sent it west to the Khwarazmian city of Otrar, an important caravan city in what is today Kazakhstan (Otrar itself no longer exists). The governor of Otrar, a man named Inalchuq, received the caravan, seized the goods, and had the merchants executed as spies. As far as I know there is no extant evidence that they were spies, though in 13th century Eurasia the lines between “spy,” “merchant,” and “envoy” were probably pretty blurry. I’m sure had the merchants survived and returned home they would have been questioned about what they saw, for example. Still, the intention behind the caravan seems to have been commerce first and foremost, not espionage.

We don’t know whether Inalchuq executed those merchants on Muhammad II’s orders. What we do know is that when Genghis Khan responded by sending three envoys to Samarkand, demanding that Inalchuq be punished and stressing that the Mongols were no threat to Khwarazm, the shah had one of those envoys executed and sent his body back with the other two. This was the first of Muhammad’s bad decisions and probably the most consequential, though there would be more to come. In fairness, as I said above there’s reason to believe he wanted to pick a fight with the Mongols and he really couldn’t have known what kind of biblical-scale retribution he was inviting upon his kingdom.

Violating the sanctity of envoys is kind of a recurring pattern in Mongolian history and there’s some reason to believe the Mongols themselves welcomed this sort of thing because they felt it gave them the justification to go to war. Going to war without justification could upset Tengri, the traditional Mongolian sky god, or any of the other deities the religiously flexible Mongols picked up along the way. So it could be argued that Genghis sent that embassy in order to bait Muhammad into doing something untoward. But in this case I have my doubts, because again it seems like it would have made more sense for the Mongols to finish off the Jin than to start an entirely new campaign. Moreover, to my knowledge there’s nothing to indicate that Genghis Khan was already making preparations to invade Khwarazm when he sent the envoys, which you’d think he would have been doing if the embassy had been a deliberate ruse to provoke a war. He had to leave a small force behind to keep an eye on things in northern China and, as it happened, those things got worse for the Mongols while he was off invading Central Asia. More on that below. The upshot is that this invasion seems like it was hastily thrown together in response to an unexpected stimulus, though of course we can’t know that for sure.

Mongolian sources tell us that Genghis Khan, irritated by the execution of those merchants at Otrar, viewed the execution of his envoy as an affront of the highest order. He was so offended that he shifted gears mid-war, leaving a small force in northern China to prevent a Jin resurgence and taking the vast majority of his army west to deal with the Khwarazmians. We don’t know how many men Genghis Khan had at his command when he marched west. There are a number of Islamic sources, some friendly to the Mongols and some not so friendly, who have them going west with 400,000-600,000 men or more, which is absurd and should be read as “a lot.” Given the supply requirements of the mostly cavalry Mongol army, whose fighters brought multiple mounts with them on campaign, modern historians tend to think maybe 100,000-120,000 is a rough upper limit to how large the force could have been.

We also don’t know how many men the Khwarazmians had and that’s largely because of Muhammad’s next questionable decision. Rather than assembling his forces to meet the Mongols in a big battle in the open field (probably a bad idea) or massing them in one or two major cities to try to withstand a Mongol siege (maybe not such a bad idea), Muhammad dispersed them into relatively small garrisons in cities throughout the empire. It seems he didn’t entirely trust many of his senior generals, a number of whom had been working for other kingdoms (the Kara-Khanids, the Qara Khitai) not that long ago, so he was unwilling to leave himself vulnerable to them by assembling them all in one place. He also assumed that the Mongols, like other steppe invaders before them, would raid the countryside and carry off what they could but would be incapable of besieging cities. You know what they say about assuming. In this case, in addition to making an ass of you and me Muhammad’s decision may have helped get lots of people killed.

What Muhammad apparently didn’t know is that the Mongols had years earlier figured out how to besiege fortified cities—they had to, if they were going to defeat the Jin. Mostly this involved forcing Chinese engineers and other specialists to join the Mongol army and make siege engines, but the morality of their tactics aside the point is that by the time they moved against Otrar the Mongols were more than capable of taking cities. Muhammad’s dispersal of troops around the empire seems mostly to have ensured that a) there wouldn’t be enough forces in any one city to resist the Mongols, and b) there would be just enough forces in many of the cities to hold out and annoy the Mongols, which guaranteed those cities a violent reckoning.

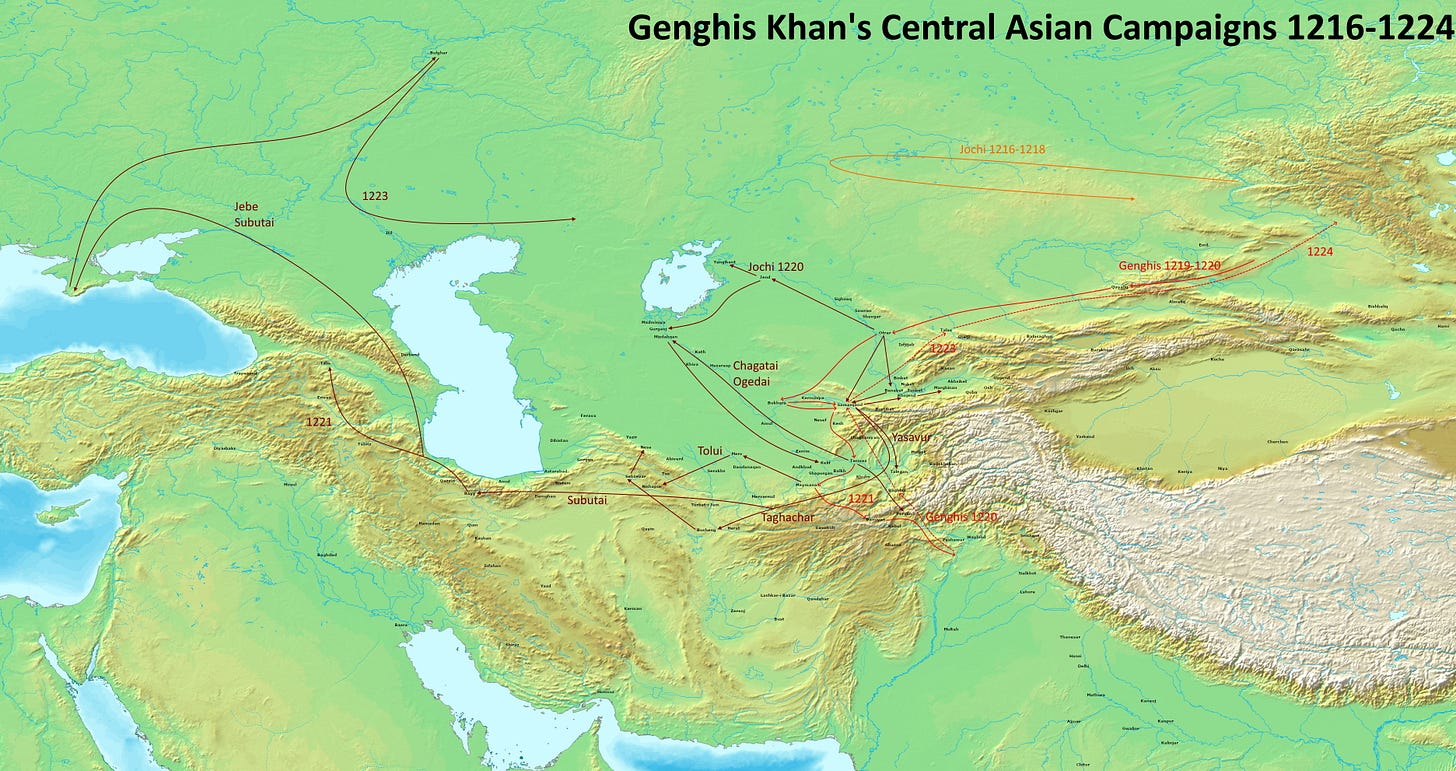

While the Mongol army was still assembling for the big move west, Genghis Khan sent an advance force commanded by his second1 son Chagatai and third son (and future heir) Ögedei to lay siege to Otrar in late 1219. The rest of the army followed but Otrar’s garrison put up a stubborn resistance despite the odds being decidedly stacked against them. Presumably noting that Muhammad had conceded the countryside to the Mongol army, Genghis Khan decided to divide his forces. He sent one part under his eldest son Jochi to the west and a bit north along the Syr Darya (Jaxartes) River and another part south under two senior generals, Jebe and Subutai. He took the remainder, along with his youngest son Tolui, and moved west and a bit south to besiege Bukhara. Chagatai and Ögedei were left to complete the conquest of Otrar.

The decision to move on Bukhara first rather than Samarkand appears to have crossed Muhammad II up a bit but from a strategic standpoint it was very smart. Had Genghis Khan moved against Samarkand first the Khwarazmians could have sent relief forces from Bukhara to try to catch the Mongols from the rear. By contrast, they were not going to send a relief army from Samarkand to try to rescue a less important city like Bukhara and risk leaving their capital undefended. Bukhara fell quickly—most of the forces stationed there marched out of the city, intending either to give battle in the open field or make a break for it. Whatever the rationale, they were annihilated by the Mongols and the rest of Bukhara’s garrison surrendered a couple of days later, on or about February 10. In the first of several atrocities to come the Mongols slaughtered the garrison and enslaved pretty much everybody else. They sent the women and any men with useful skills back east, and took the rest of the population to serve as either forced labor (if they were lucky) or human shields (if they weren’t) on the Mongols’ next operation, the siege of Samarkand.

Genghis Khan and Tolui advanced on Samarkand, stopping only to squash a few towns along the way to deepen the city’s isolation. Sometime after beginning their siege they were joined by the Mongol force that had finally completed the sack of Otrar. I haven’t seen a reliable estimate of the number of people who died either defending Otrar or in the aftermath of that siege but it may have been substantial given that the city’s garrison had held out and made itself a nuisance, and that Otrar had been the site of the Khwarazmians’ first insult to the Mongols. One person who definitely did not survive was Inalchuq, the author of that insult. Mongol legend has it that the Mongols poured molten silver into his eyes and mouth. This seems unlikely, as the Mongols generally didn’t go in for dramatic executions of this sort and they presumably wouldn’t have wanted to waste the silver. That said, if anybody was going to get an elaborate, especially painful execution at Mongol hands it was going to be Inalchuq. So who knows?

Samarkand was better defended than Bukhara but it wasn’t able to withstand a siege, especially without support from Bukhara and the surrounding towns. Shah Muhammad appears to have attempted a defense, but when he was unsuccessful he hightailed it to safety in relatively short order. He was apparently not the sort of captain who would go down with the ship, as it were. Despite his departure, or perhaps because of it, Samarkand’s garrison is said to have held out for around a month, and while that time frame doesn’t necessarily align well with Juzjani’s March 19 date for the fall of the city let’s just go with it anyway. As with Bukhara the Mongols killed the garrison but were relatively lenient with the civilian population in that they merely enslaved it. Samarkand as a city struggled to recover, but the rise of the Turco-Mongolian warlord Tamerlane in the 1370s saw it become the capital of a new steppe empire and its fortunes improved substantially.

The Mongols moved on conquer the rest of the Khwarazmian Empire city by city, committing some of the most notorious massacres in history along the way. They destroyed the cities of Gurganj (modern Konye-Urgench in Turkmenistan), Merv (near modern Mary in Turkmenistan), and Nishapur (in modern Iran) and put most of their civilians to the sword, killing probably hundreds of thousands of people in each case. All three cities had resisted Mongol conquest and the massacres were apparently the price for that resistance—by contrast the city of Herat (in modern Afghanistan) surrendered peacefully and its people were largely spared.

While this was happening Shah Muhammad fled west, chased by Jebe and Subutai, until he eventually died of illness while hiding out on an island in the Caspian Sea. His son, Jalal al-Din, fled south and tried to marshal whatever forces he could assemble. Almost miraculously, he apparently put together a pretty substantial army and was actually able to defeat a Mongol force at the Battle of Parwan (in modern Afghanistan) in September 1221. Genghis Khan then decided to chase down Jalal al-Din himself and broke his army in a battle on the Indus River (in modern Pakistan) in November. Jalal al-Din survived and remained an irritant to the Mongols for the next several years, finally dying in 1231 while on the run in a region that’s now part of Turkey. The Khwarazmian army that was following him at his death took on the quality of a mercenary band before they were finally crushed by the Ayyubid dynasty of Egypt and Syria, and its Turkic slave soldiers—the future Mamluks.

After the battle on the Indus Genghis Khan seems to have decided it was time to return his attention toward China, particularly once he’d experienced the Indian climate and decided that it was not to his liking. The previously subjugated Xi Xia were making trouble for the commander he’d left in charge back east and he resolved to put an end to it. He spent the next several years slowly working his way back to Mongolia, reaching it in 1225, then spent much of 1226 and 1227 crushing the Xi Xia so thoroughly that historian John Man has said that “there is a case to be made that this was the first ever recorded example of attempted genocide.”2 He was planning to resume his campaign against the Jin when he died in 1227.

Real Mongol heads will know that Genghis Khan’s acknowledged eldest son, Jochi, was born a conspicuously short time after the Mongol ruler (who was still just plain old Temüjin at the time) rescued his wife, Börte, from her abduction by a group of Merkits sometime around the year 1178. I don’t want to say that Jochi was definitely the product of rape while Börte was held captive, but that was thought to be a real possibility at the time and historians haven’t refuted it. So in a strictly biological sense Chagatai may have been Genghis Khan’s eldest son and Ögedei his second son. But Genghis Khan accepted Jochi as his eldest son regardless of the parentage question and that’s how we’ll treat him here.

Man, John, Genghis Khan: Life, Death, and Resurrection (Thomas Dunne Books, New York: 2004), 117.