The Decline and Fall of Area Studies

Federal funding cuts and attacks on academic freedom are imperiling area studies programs. It’s important to understand what they are, and aren’t—and what will be lost if they disappear.

This column is free to everyone. To receive more in depth analysis of US foreign policy and international affairs, sign up for Foreign Exchanges’ email list today! And please consider subscribing to support the newsletter and help it continue to grow:

Amid the cuts imposed by the Trump administration and the “Department of Government Efficiency” (“DOGE”), it has been strange and sad to see the destruction of many programs and institutions that funded my research and made my career possible, along with the careers of countless mentors and colleagues. I think of myself partly as an area studies researcher—that is, someone interested in studying places for their own sake rather than as “cases” that help inform supposedly universal “theories.” Under Trump, the infrastructures that support much area studies research in the United States have been badly damaged. Most worryingly from the perspective of academic freedom, many area studies programs and departments have attracted negative attention from both Washington and their own university administrations—especially Columbia’s Department of Middle Eastern, South Asian, and African Studies.

The destruction has made me think about the ambiguity of area studies as an enterprise. On the one hand, the field took its present form amid and because of the Cold War, with the federal government delivering much of the funding and setting many of the priorities. Area studies also received a late boost from the War on Terror, reinforcing its dependence on federal funding structures and its attachment to “national security.” On the other hand, area studies scholars have often been at the forefront of questioning US foreign policy. Had the decision-makers listened, many mistakes and tragedies might have been avoided, including the Iraq War.

The US, a deeply parochial empire, does not ultimately need regional experts to advance imperial projects. Imperial power is largely exercised from the White House, the Eisenhower Executive Office Building, and the Pentagon—and from fortress embassies on the outskirts of foreign capitals. If the United States is going to bomb Yemen no matter what, across five presidential administrations and counting, then the White House does not need people who have lived in Sanaa or Aden, who speak Arabic, or who understand the significance of 1962 or 1990. In a way, the defunding of area studies institutions represents not just the recklessness of Donald Trump and Elon Musk but also an acknowledgment of the crude reality that the US government can project power without regional specialists. The real loss, then, is not to “national security” but to the depth of connection that American society itself has with the rest of the world.

An Autobiography in Funding

My own experience—that of a provincial intellectual who has nevertheless had significant contact with the state—can offer a small case study of the last gasp of a certain area studies model in the US.

In 2005, I finished my undergraduate studies in Religion and cast about for something to do next. I had written my senior thesis under the supervision of the great Senegalese philosopher Souleymane Bachir Diagne, now at Columbia, and I wanted to move from studying classical Islamic thought to studying living Muslim societies. With Prof. Diagne’s gracious support, I applied to the Fulbright Scholarship and received it, spending nine months in Senegal from 2006 to 2007.

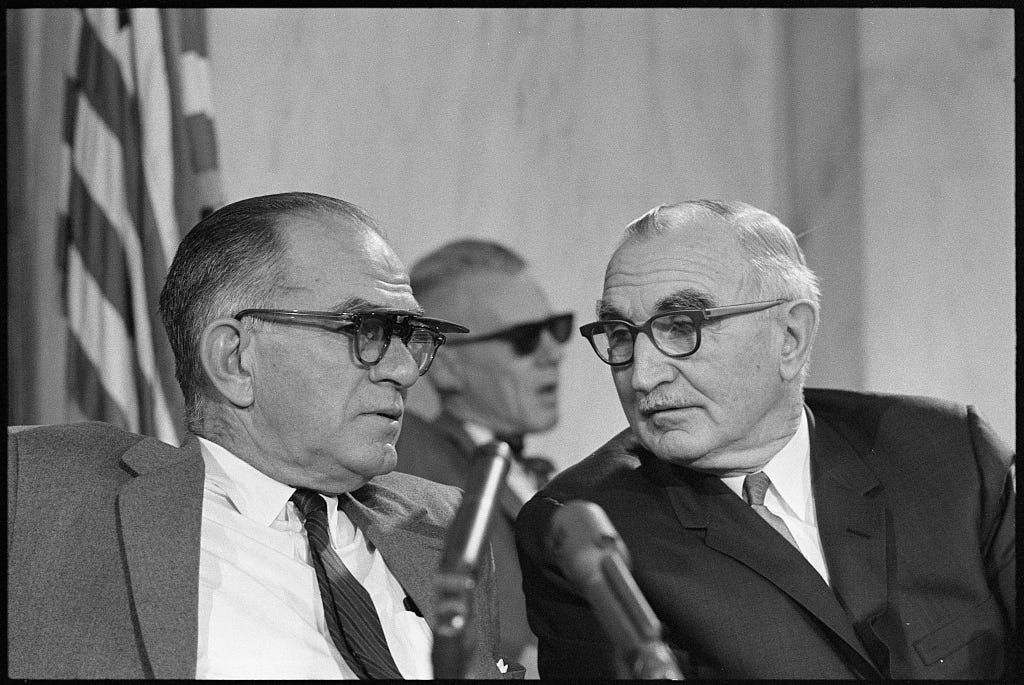

The Fulbright Scholarship is named for Senator J. William Fulbright (1905-1995). Fulbright had been a Rhodes Scholar—which was itself a scholarship that emerged out of Britain’s empire, having been created by British colonialist and mogul Cecil Rhodes (1853-1902), the founder of “Rhodesia.” The Rhodes Scholarship brings rising elites from Britain’s former colonies to study at Oxford. Fulbright envisioned his own scholarship, established through an act of Congress in 1946, as a cultural exchange program that would promote peace in the aftermath of World War II. The emerging Cold War context was also crucial, however. Fulbright himself charted a complex relationship with the Cold War, emerging in the 1960s as a formidable critic of the Vietnam War. The Fulbright program, meanwhile, became a key feeder mechanism for not just academia but also the State Department and the US government more broadly.

After my Fulbright year, I went to Georgetown from 2007 to 2009 for an M.A. in Arab Studies. I had gotten serious about learning the Arabic language and I was also interested in studying religious and political interconnections between West Africa and the Middle East. At Georgetown, my second year was funded through the Foreign Language and Area Studies (FLAS) program, which is (was?) a Department of Education program. FLAS scholarships were created through the 1958 National Defense Education Act (NDEA), itself a response to the Soviet Union’s launch of the Sputnik satellite the previous year. The NDEA funded “hard sciences” as well as social sciences and area studies; one component was what are called Title VI centers, meaning academic units specializing in particular regions of the world.

As I was wrapping up at Georgetown, I received another scholarship, from the Center for Arabic Study Abroad (CASA) based at the University of Arizona. The CASA program was created in 1967 with NDEA funding. I didn’t ultimately accept the CASA scholarship (though I should have!) and instead headed to Northwestern for a Ph.D. in Religious Studies. The history of Arabic instruction in the US is yet another case study of the centrality of government funding and priorities, as well as the intertwined nature of government and universities.

At Northwestern, where my research focused on Islam in northern Nigeria, the funding for my fieldwork in 2011-2012 came from private foundations—namely, the Social Science Research Council (SSRC) and the Wenner-Gren Foundation. But it could have easily come from the US government again. I was rejected for a Fulbright-Hays Doctoral Dissertation Fellowship, which has funded many of my colleagues’ work over the years. One should note too that foundations such as SSRC, Mellon, and particularly Ford, along with the National Science Foundation, are part of the same Cold War milieu that produced the Fulbright and those NDEA-funded programs.

There were also various federal awards that I either didn’t apply for or didn’t end up accepting, such as the Boren Fellowship (created through the Boren National Security Act of 1991, named after Democratic Congressman David Boren, who died this February). Long story short, to receive advanced language and area studies training in this country and to conduct overseas fieldwork, the best-funded and most prestigious pathways ran through the federal government or adjacent institutions.

For graduate students interested in advanced language study and overseas fieldwork now, pathways have considerably narrowed. The SSRC has—wrongly in my view—almost completely abandoned area studies in favor of focusing on technocratic, liberal domestic policy initiatives. Federal funding was getting tighter even before Trump returned to power. The collapse of funding structures for fieldwork also reinforces inequalities between universities. Federal funding and foundation funding was never a total equalizer, given that students at elite universities often have multiple advantages when applying for those programs, but now even more than before students at top schools can rely on internal funding resources that students at other schools typically don’t have.

Since finishing my Ph.D., my work has been supported at several moments by federal funding, for example when I spent an academic year at the Wilson Center in Washington. Created by an act of Congress in 1968, the Wilson Center became a key destination for area studies scholars. One of the Center’s most prominent units is the Kennan Institute, created by the famous diplomat George Kennan (1904-2005) in 1974. Kennan was one of the early intellectual architects of the Cold War, including through his famous “long telegram” of 1946. Many of these institutions, then, have a Cold War pedigree and/or echoes back to the period immediately after WWI and the drive to shape the postwar order. The SSRC and the Council on Foreign Relations, the latter of which funded a year-long fellowship I spent at the State Department working on Nigeria, were both founded in the early 1920s.

Many of these opportunities have now been slashed. The Wilson Center, for example, has been reduced to a shell under Trump. I cannot imagine all of the cascading effects for individual scholars—lives rerouted, work disrupted, etc. There will also be systemic effects in terms of greatly curtailing the horizons for writing and research; many books will go unwritten in the coming years due to these disruptions. Some of the funding will eventually be restored, I imagine, but the incentive structures and risk assessments may seriously change in the intervening years. Academia was already a fraught career path, and an area studies focus even more so. I wouldn’t advise anyone to pursue an area studies career now.

What Is Area Studies For?

During the Cold War, as the government funded area studies, the resulting expertise was always first and foremost valued for what it might contribute to geopolitical dominance. When specialists advanced arguments that were at odds with perceived American national interests, those specialists and their arguments were sidelined—or worse. Both within the government and outside it, regional experts could fall on the wrong side of shifting policy winds. David Halberstam, in his famous book The Best and the Brightest, writes that in the State Department, “All of the China hands…had their careers destroyed with the fall of China [in 1949]. The men who gave advice on China were either Europeanists or men transferred from the Pentagon.”1 In academia, the most infamous champions of the Cold War were political scientists such as Henry Kissinger and Samuel Huntington, who were generalists rather than regional specialists.

My own limited experience in interacting with policymakers suggests that area studies has little impact on policies and decisions. During the Obama administration in particular, I was invited fairly frequently to conferences and briefings. At the time, my theory of change (which now seems so quaint and dubious to me) was that I could introduce some “nuance” into policy discussions and in this way contribute to reducing militarism and Islamophobia—but how exactly that “nuance” was supposed to move from the low-level bureaucrats and analysts at these events (assuming they even cared what I had to say) to senior-level decision-makers was a question I could not have answered. In 2013-2014, an International Affairs Fellowship from the Council on Foreign Relations allowed me to serve in government, as a Desk Officer for Nigeria in the State Department’s Bureau of African Affairs, but even in the meeting rooms of Foggy Bottom, I had effectively no influence. Fresh off of my doctoral fieldwork in Nigeria, I was sure that policymakers would be eager to hear my views. But no senior official displayed even the slightest interest in listening to me during twelve months in government. Inside the State Department, hierarchy was all. So of what good were all these investments in area studies scholars?

Ultimately, there is a tension between the world-remaking aspirations of imperial policymakers and the nuances, cautions, and subtleties that deep area studies concentrations generate—especially in an era of rapid communications and mass-casualty weapons. Whereas earlier empires required local administrators with considerable knowledge of their surroundings, the American empire has primarily featured generalists in Washington attempting to impose projects on the periphery; it is an empire of Donald Rumsfelds, Jake Sullivans, and Jared Kushners, and less an empire of Lawrences or Lugards.

Britain and other colonial powers committed horrendous atrocities and saw the world through a fundamentally distorted and racist lens, but their exercise of power was different from the American version. Throughout much of their empire the British had to rely on the “man on the spot,” who had to have some linguistic, cultural, and political proficiency. The American empire, less about the direct administration of territory than the projection of power, requires neither local competency nor even policy success. Backed by a ridiculously favorable geographic position and tremendous natural and accumulated wealth, US ventures can fail in the peripheries again and again without imposing fundamental costs on the core. The Trump administration’s cuts to federal funding for area studies will be devastating to academia, but ultimately won’t derail the exercise of imperial power. If the colonial model involved weaponized knowledge, the American empire coasts on weaponized ignorance.

The cost of cuts to area studies, I think, is twofold. First, the US will become an even more parochial society. The vast funding opportunities the US government provided may not have resulted in policymakers listening to critics, but those funding structures did produce a deep bench of people who can speak with serious knowledge about different parts of the world, enriching the undergraduate classroom, providing interlocutors for journalists, and yielding many fantastic books. When people ask me for reading lists on West Africa, for example, many of the books I mention are the outgrowth of Fulbright-Hays years, Wilson Center Fellowships, etc.

Now, however, academia is unlikely to pick up the slack as far as area studies funding is concerned. In political science, for example, the prestige topics have to do mostly with “theory” rather than with the generation of empirical knowledge about specific parts of the world. As Michael Desch and others have written, the search for supposedly greater methodological rigor drove political science away from area studies and towards heavily quantitative approaches based on models and abstract theories. That process, unfolding over decades, has marginalized area studies within the top journals and within political science departments.There are still highly active area studies associations—the Middle East Studies Association and the African Studies Association, among others—but their capacity to fund research is a tiny fraction of that of the federal government. Combine the decline of area studies within academia with the cuts to many major newspapers’ staff of foreign correspondents, and you have a society that certainly has more access than ever before to news and perspectives from overseas, but fewer people with the deep training to interpret what events overseas mean. That’s a loss that will be felt well beyond the Trump years.

Second, critically-minded area studies scholars constitute the reserve brainpower of an alternative foreign policy, should that alternative ever get the chance to express itself. “Left Foreign Policy” has often been conceived of as an alternative grand strategy, such as restraint, but that approach mirrors the abstraction of existing grand strategies—which are never consistently applied. By contrast, a patchwork, region-by-region foreign policy, drawing on detailed knowledge of local conditions, can at least help anticipate the unintended consequences that have attended so many US foreign policy choices. The 2015 Iran Deal, in which area experts such as Rob Malley and Ali Vaez played key roles inside and outside government, is just a glimmer of the type of openings that might be possible if the US embraces some sensitivity to the other country’s perspective. (The importance of those experts’ role also helps to explain the high degree of scrutiny they have faced.) Not all area studies scholars are critics, of course, nor are they always effective when brought into government (see Michael McFaul, a thoroughly establishment figure, for example). But without a cadre of people who have done deep research on and in other countries, the US will stumble through the world more blindly than ever.

David Halberstam, The Best and the Brightest (New York: Ballantine Books, 1992 [1972]), xviii.