GUEST POST: Using Middle Eastern Christians for Imperial Aims

I’m very excited to bring you our first Foreign Exchanges guest post! Georgetown University’s Joshua Mugler looks at the Trump administration’s “defense”of Middle Eastern Christians and places them in the context of similar–and generally cynical–past claims.

If you would like to pitch something for Foreign Exchanges, please email me. And if you enjoy this content, please consider subscribing to support more guest writers:

by Joshua Mugler

At the first “Ministerial to Advance Religious Freedom,” held in Washington in July, Vice President Mike Pence and Secretary of State Mike Pompeo declared the willingness of the United States government to intervene on behalf of persecuted religious minorities around the world. Pence called out violations of religious liberty by most of the countries against whom the US is officially hostile—Iran, North Korea, China, Russia, Nicaragua, and so on—while ignoring similar repression by American allies and client states. He announced the creation of several new initiatives by which the government plans to intervene directly in other countries on behalf of religious minorities and threatened sanctions on Turkey for its imprisonment of an American missionary (the sanctions were imposed on August 10).

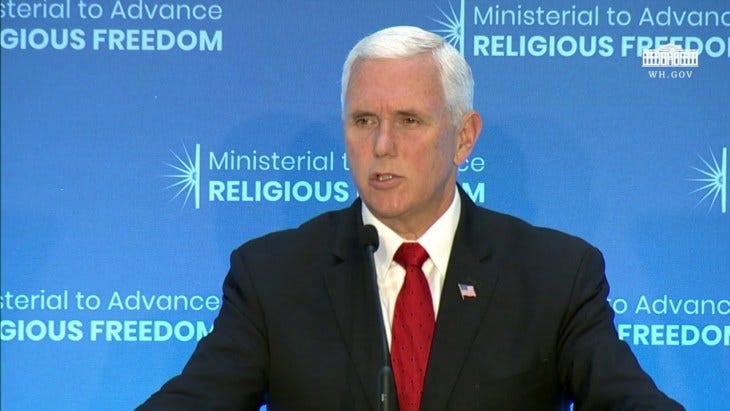

U.S. Vice President Mike Pence speaking at the “Ministerial to Advance Religious Freedom” on July 26 (YouTube | WhiteHouse.gov)

Much of Pence’s discussion was focused on the Middle East, where he called for the protection of a variety of religious minority groups and spoke against ISIS. At this event he tried to devote attention to a broad range of groups, but in the past he has most often focused specifically on Middle Eastern Christians. Throughout the recent wars in the region, the various minority groups of Syria and Iraq—especially Christians—have frequently been depicted as oppressed and threatened people who need our help, whether in the form of a full invasion or another type of military intervention. Even with ISIS largely in retreat, such rhetoric continues to be used to justify the never-ending presence of the American military in the region. In addition, the Trump administration has explicitly pursued policies that would allow the United States to take in Middle Eastern refugees of minority religions while rejecting Muslim refugees, leading some Middle Eastern Christian leaders to speak out against such sectarian favoritism.

None of this is new: Christian-ruled Western states have long used Christian and other minorities to the East to justify their imperial interventions and wars. Eusebius of Caesarea tells us that the Roman Emperor Constantine (d. 337) sent a letter to Shah Shapur II (d. 379) insisting that he treat his Christian subjects well or face imperial wrath. Pope Urban II (d. 1099) launched the First Crusade with a speech that appealed to European Christians to defend their Middle Eastern fellow believers, who Urban insisted were suffering grotesquely at the hands of their Muslim rulers. However, the power of modern Western empires to shape the region’s politics, even in territories that they do not officially control, is far beyond anything the Romans or Crusaders could conceive.

One particular historical analogue that may help us understand this phenomenon is the Crimean War of the 1850s. In the late 1840s, to set the stage, tensions were high between the Christian denominations of Palestine. Each Holy Week in Jerusalem and each Christmas season in Bethlehem seemed to bring a new conflict between representatives of the Roman (or Latin) Catholics and their Greek Orthodox and Armenian rivals. These three denominations comprised the vast majority of local Christians and shared possession of the most prestigious holy sites in the area, the Church of the Holy Sepulchre and the Church of the Nativity, but their relations tended toward the tense. In 1847, for example, a silver star marking the birthplace of Jesus disappeared from its place. When each group blamed the other for the theft, fighting broke out.

These conflicts were not entirely new, but the wider world was taking a greater interest in them than ever before. The French consul for the area, who openly took the side of the Catholics in these disputes, presented himself to the local Christians as a new Crusader. By 1847, he was claiming to be “Protector of Christianity in the East, or some such title,” according to the records of the British consul, and in 1858 he began regularly assigning soldiers to monitor Christmas celebrations in Bethlehem, because “one can never be sure beforehand that there will not be a riot of the Orientals.” The Russians, on the other hand, took the side of the Orthodox, while the British often advocated for the area’s nascent Protestant community, occasionally stepping in on behalf of Jews and Druze as well.

The conflicts in the Holy Land led the Russian government to assert its status as protector of all Orthodox Christians under Ottoman rule, and an ultimatum was issued in April 1853 demanding imperial recognition of this claim. Tsar Nicholas I insisted that he had no interest in expanding his own empire, but simply had an altruistic duty to protect his fellow Orthodox against their oppressors, whether Christian or Muslim. Meanwhile Napoléon III, who had recently declared himself Emperor of the French, pressured the Ottomans not to give in to Russian aggression, insisting instead on expanding the rights of Ottoman Catholics. By the end of the year, the Crimean War had broken out, and though many Orthodox sympathized with the Russian side, numerous Catholics expressed their support for the Ottoman “jihad.” The British, French, and Ottomans held off Russian advances through three brutal years of fighting and secured a favorable treaty in 1856. In the wake of their assistance in the war, the Western governments were able to pressure the Ottomans to issue a far-reaching reform edict that theoretically stripped away many longstanding Muslim privileges.

Again, none of this imperialist interaction with local Christians was new, except in scale. European governments had long employed local—primarily Christian—intermediaries known as “dragomans” to translate in official settings and facilitate their commercial enterprises. Missionaries had come from all parts of Europe and (starting in the early 19th century) the United States, generally relying on the protection of either the French or British government according to their denominational affiliation. International Christians and their clients were familiar sights in Ottoman territory.

Did this foreign support improve the lives of Ottoman Christians? Certainly some of them, such as the dragomans—who enjoyed imperial prestige and were exempt from many Ottoman laws—benefited from the arrangement. Yet the selective nature of European intervention fomented sectarian and anti-imperialist hostility as well. For example, when local officials of Church and state reacted to the 1856 reform edict by ringing church bells and flying French flags in Nablus, protesting Muslim groups took to the streets. One such group encountered a Protestant missionary, and when the missionary panicked and killed a man, the crowd began to ransack symbols of the foreign powers, such as flags, church bells, and the homes of Protestants and Muslim collaborators. When an 1860 civil war between Maronite Catholics and Druze in Mount Lebanon spilled out of the mountains and led to deadly sectarian riots against the Christians of Damascus, many poor Orthodox Christians were protected by their Muslim neighbors, while wealthier Catholic areas with French connections were devastated. Wealthy Christians, especially foreign missionaries and their local protégés, were thus often seen as extensions of the foreign governments that were gradually eroding Ottoman autonomy, and attacks on mission outposts were not uncommon. This is all in addition to the Christians who were harmed by fighting encouraged or perpetrated by the Western powers, whether on the battlefields of the Crimean War or at the Church of the Nativity.

Western imperial intervention on behalf of Levantine religious minorities reached new heights in the 20th century, when the British and French took over the entire region in the wake of World War I. France carved Lebanon out of Syria in order to establish a country with a Christian majority (but complicated matters by including the Muslims of the coastal cities within its borders), while the British set about creating the Jewish homeland that they had promised in the Balfour Declaration. The backlash against these acts of selective patronage has been made manifest in the continuing Palestinian resistance to Israeli rule and in the complex Lebanese Civil War, itself a jumble of different foreign patrons—French, American, Soviet, Syrian, Saudi, Israeli, and so on—intervening on behalf of their favored sectarian and political militias.

Though US officials largely downplayed the defense of religious minorities in favor of “democratization” as justification for their 2003 invasion of Iraq, American Christian missionaries again saw this war as an opportunity to pursue their work in the region. The aftermath of the invasion, of course, has decimated Iraq’s Christian community, over half of which has fled the country in the face of repeated attacks. More recently, the rise of ISIS has brought defense-of-minorities rhetoric back to the fore, often serving hawks as a desperately needed rationale for military intervention to an American public that is wary of new Middle Eastern entanglements.

Christians in the Middle East have often felt trapped between several bad options. Should they assert undying loyalty to whichever ruler is currently in power (incredibly risky in times of political chaos)? Should they seek out alliances with foreign, Christian powers (and risk the resentment of their neighbors)? Or should they flee to Christian-ruled territory and abandon their homelands? How best to secure the safety of Middle Eastern Christians, and other religious minorities, is far from clear, but military intervention tends to create political chaos, to inflame sectarian and other hostilities, and to displace numerous members of this already small minority. Rhetoric that justifies military aggression by asserting the need to defend America’s oppressed Christian cousins should be seen for the longstanding imperialist tactic that it is. It was used (and not for the first time!) by the British, French, and Russians to obtain increasing control over the slowly collapsing Ottoman Empire, and it is used by the United States and other powers to manipulate the Middle East today.

Josh Mugler is a PhD candidate in Theological and Religious Studies at Georgetown University. He specializes in the history of Muslim-Christian interactions, especially in the medieval Middle East, and is fascinated by the interplay of religious identity and place. Originally from the St. Louis area, he now lives in Durham, North Carolina. Follow him on Twitter @j_mugs.