Today in South Asian history: the Battle of Diu (1509)

A Portuguese fleet wins a major naval victory and a foothold in India.

If you’re interested in history and foreign affairs, Foreign Exchanges is the newsletter for you! Sign up for free today for regular updates on international news and US foreign policy, delivered straight to your email inbox, or subscribe and unlock the full FX experience:

The appearance of Portuguese explorers in India in 1498 was, it’s safe to say, a world-altering event. When Vasco da Gama proved that it was possible for European ocean-going vessels to reach India by going around Africa, it meant changes not only for Europe and India, but for the kingdoms in between, whose economies had depended to one extent or another on extracting rents from commercial traffic along the various Europe-to-India routes. Here I’m talking about a number of Muslim states—the Ottomans, the Mamluks, the various dynasties that controlled northern India and Iran. But I’m also talking about Christian Venice, which made a lot of bank ferrying eastern luxuries across the Mediterranean Sea to European customers.

The arrival of seafaring Europeans changed things for India too, let’s not minimize that. It took a while for the full effect to be felt, and by the time it was fully felt Britain had displaced Portugal, but obviously Indian history would look a lot different if the Europeans had never arrived. Their impact may not have manifested for a while—the most powerful of the Muslim Indian kingdoms, the Mughal Empire, hadn’t even been established yet by 1509, when today’s story takes place—but manifest it ultimately did.

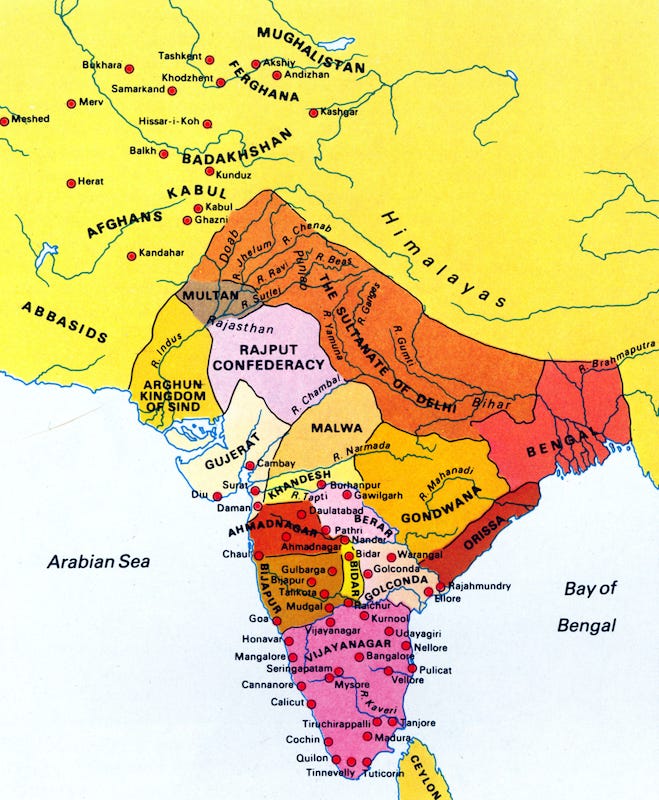

I’m getting way ahead of myself though. The Portuguese arrival was not well-received in the ports of southwestern India, in cities like Calicut (look closely at the map below). Those areas were frequently used by Arab merchants, who had already driven off a Chinese attempt to establish commercial outposts there. The merchants may have colluded to engineer a similar fate for the Portuguese, or the Portuguese may have gotten dragged into local political disputes, or both, or something else altogether, but whatever the cause things broke very badly in late 1500. That year, Pedro Álvares Cabral, a Portuguese noble with apparently no seafaring experience, sailed a fleet into Calicut harbor where it...just sat, for months, waiting to buy enough spices and other goods to fill its cargo holds for the return trip to Europe. In December, frustrated by what he saw as a concerted plot to lock him out of the market, Cabral seized an Arab ship in the harbor and took its goods. In response, a mob organized by the port’s Arab merchants massacred at least 50 Portuguese people onshore.

With Calicut no longer friendly territory, the Portuguese reached out to the nearby state of Cochin, nominally a vassal of Calicut but ruled by a raja who wasn’t terribly happy with that arrangement. The Gujarat Sultanate, located in northwestern India and one of those trade intermediaries I talked about above, decided to throw in with Calicut as a way of hopefully getting rid of the Portuguese, and they sent to Cairo asking for help from the Mamluks—arguably the kingdom that had the most to lose from the establishment of direct Europe-to-India trade, since it controlled the main Red Sea route for Indian goods heading to Europe. On top of that, the Portuguese had begun to encroach on Mamluk territory, capturing the island of Socotra (which today is part of Yemen) in the Arabian Sea.

The Mamluks and Venetians were already feeling the pinch as Portugal began bringing Indian goods back to Europe via the around-Africa route, so they decided to Do Something about it (Doing Something, as you know, is always a good idea). Since the Mamluks, who specialized in mounted archery, weren’t particularly noted for their naval capabilities, Venice provided several Mediterranean carracks and war galleys along with Greek crews. Venetian shipbuilders disassembled the vessels for the overland trip from the Mediterranean to the Red Sea, then reassembled them for the nearly two-year (they had things to do along the way and the monsoons didn’t cooperate) voyage to the port of Diu, in Gujarat. They arrived in late 1507.

The Portuguese fleet was outnumbered, but it likely outgunned its adversaries and certainly outclassed them if it came to combat. The Mamluks did have a few large vessels, but the bulk of their fleet was made up of tiny Indian dhows, which were generally too small for cannon. The Portuguese fleet included state-of-the-art carracks and caravels, ships that were built to withstand the rigors of long ocean travel and were packed with guns. When it came to ship-to-ship fighting the Mamluks brought archers, while the Portuguese soldiers were armed with gunpowder firearms and grenades. You get the idea. Despite this technological imbalance, however, at the Battle of Chaul in March 1508, the Mamluk/Gujarati fleet caught a small (maybe 8 ships and no carracks) Portuguese fleet by surprise and came away victorious. It was the first time the Portuguese had been defeated in the Indian Ocean.

It so happens that the Portuguese fleet at Chaul had been commanded by the son of the Portuguese viceroy in India, Francisco de Almeida, and he (the son) was killed in the fighting. Francisco, as you might expect, had a mind for vengeance, and as he was due to be replaced as viceroy he had to move fast if he was going to get it. He sent a letter to Malik Ayyaz, the Gujarati governor of Diu, announcing his intentions:

“I the viceroy tell you, honored Meliqueaz, captain of Diu, that I come with my knights to your city, to spear the people who shelter there, after they attacked my people in Chaul, and they killed a man who was called my son; and I come with hope in God of Heaven to take revenge on them and those who help them; and if I do not find them I will take your city in payment, and you, for the help you gave them at Chaul. I tell you this so that you will know that I go, as I am now on this island of Bombay, as the bearer of this letter will tell you.”

The Mamluk commander, Amir Hussain al-Kurdi, was aware of his fleet’s weakness, so he kept it in Diu’s harbor in a defensive position. This turned out to be a bad idea. Hussain’s decision to keep his ships lashed together in a line left them practically immobile, unable to react to what the Portuguese did. The geography of the harbor forced all those small dhows to bunch together, which made them sitting ducks for Portuguese cannon. The Portuguese fleet gradually boarded and seized the Mamluk carracks, and the Portuguese caravels were able to maneuver around the Mamluk line and bombard them from the rear.

The Mamluk-Gujarati losses at Diu were in the hundreds, compared to a couple dozen Portuguese killed. Almeida was offered the city, but realized it would probably be indefensible and opted for a large cash payment instead. Still angry about the death of his son, he executed most of his prisoners. He was replaced as viceroy later in the year, and was killed by an African tribe during the trip back to Portugal.

The most important outcome of Diu was that it confirmed that the Portuguese were in India to stay—or at least until another European power drove them out. They made an unsuccessful attempt to capture Diu in 1531, but were shortly thereafter given control of the city by the sultan of Gujarat in return for their help against the Mughals. The Ottomans, who defeated and subjugated the Mamluks in 1517, besieged the Portuguese fortress at Diu twice (in 1538 and 1547), but both of those sieges failed and the Ottomans pretty much wrote the Indian Ocean off after the second one.