Today in Middle Eastern history: the Battle of Andrassos (960)

Some quick Byzantine thinking turns a successful Muslim raid into a military defeat that shattered the powerful Hamdanid Emirate of Aleppo.

If you’re interested in history and foreign affairs, Foreign Exchanges is the newsletter for you! Sign up for free today for regular updates on international news and US foreign policy, delivered straight to your email inbox, or subscribe and unlock the full FX experience:

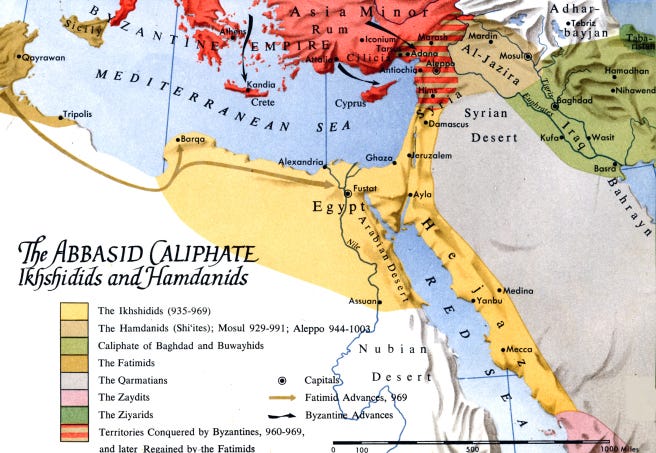

As the Abbasid caliphate lost much of its real power in the 10th century it gave way to a series of “caretaker” sovereigns in the imperial core (first Turkish slave soldiers, then later the Buyid and Seljuk dynasties) and local emirates elsewhere. These emirates were technically dynastic governorships. Most paid nominal homage to the caliph and were in turn granted the right to govern their city or territory by the man who was still titular boss of the caliphate.

Obviously there’s nothing notable about an emperor designating people to run the provinces of the empire. But as the caliphate weakened, these grants became more recognitions of reality rather than delegations of authority. The caliph, sitting helpless and in some respects captive in either Samarra or Baghdad, was increasingly cut off from the provinces, and it became easier to just leave these local dynasties in power (as long as they didn’t openly rebel or something like that) than to try to get rid of them.

One of these local dynasties was the Hamdanids. They were a Shiʿa ruling house founded by Hamdan ibn Hamdun (d. sometime after 895) under fairly inauspicious circumstances. Hamdan was actually part of a major rebellion against the caliphate in the Jazira (the area that today covers northern Iraq, northeastern Syria, and a bit of southeastern Turkey between the Euphrates and Tigris Rivers) in the 880s and was captured by the Abbasids in 895 as they were putting that rebellion down. Hamdan’s son, Husayn, immediately went over to the Abbasids, and his military service was so exemplary that he not only managed to secure his rebel father’s freedom as well as key imperial appointments for his brothers, but managed to get himself appointed governor first of the Jibal region (in western Iran) and then of the city of Mosul.

Husayn rebelled against the Abbasids in 915 or thereabouts and was executed in 918, but the family’s fortunes were not really damaged by that hiccup. On the contrary—in 929 one of Husayn’s nephews became emir of Mosul under the title Nasir al-Dawla (d. ~968, “defender of the dynasty”) and in 945 another of his nephews became emir of Aleppo under the title Sayf al-Dawla (d. 967, “sword of the dynasty”). They got these titles for their military service in support of the Abbasids against a rebel group operating out of Basra. It’s Sayf al-Dawla’s branch that fought at Andrassos in 960.

Opposing Sayf al-Dawla’s Hamdanids in that battle was the oldest of Muslim enemies, the Byzantine Empire. Once installed as emir of Aleppo, Sayf al-Dawla made a point of conducting regular raids into Byzantine territory, fulfilling the traditional role of the frontier warrior for the faith. The Byzantines, ruled in 960 by Romanos II (d. 963), had begun to take advantage of the breakdown in the caliphate’s cohesion to defeat smaller Islamic principalities along the frontier. But they found in Sayf al-Dawla’s emirate an entity that was was still strong enough to resist them, and so the Hamdanid emir became their primary antagonist in this period.

In mid 960 Romanos decided to send the bulk of his forces under his commander in chief, the future Emperor Nikephoros II Phokas (d. 969), on an adventure to conquer Crete. Well, technically his father and predecessor, Constantine VII (d. 959). had decided to send Nikephoros to Crete, but he died before the expedition could get underway. Anyway, Romanos left Nikephoros’ brother, Leo Phokas the Younger, in command of the remaining army in the eastern parts of the empire. Sayf al-Dawla, who had been steadily losing ground to Leo and other Byzantine commanders, got wind of the Crete expedition and thought that this would be a perfect time to strike at the Byzantines while most of their military was deployed elsewhere. Amassing an army—estimates of its size are so varied that I won’t even bother giving you any here, basically we just don’t know—he set off into Byzantine territory and sacked the imperial military garrison at Charsianon. His raid successful, he set off back to Hamdanid territory following the same route he’d taken into the empire.

This proved to be a huge mistake. Leo Phokas had in the meantime managed to take his outnumbered army around the Hamdanids and laid a trap for them in a pass through the Taurus Mountains called Andrassos. The ground was just about perfect for an ambush. The Hamdanids had to squeeze their way into the pass, and the rocky ground made it hard for their cavalry to maneuver in whatever space they had. The Byzantines, occupying the high ground on both sides, were able to lob rocks and tree trunks down on the helpless Hamdanids, and their charge down the mountain broke Sayf al-Dawla’s army. Most of the Hamdanid force was killed or enslaved, and all the captives and booty they’d taken from Charsianon fell back into Byzantine hands. Sayf al-Dawla somehow escaped, along with a couple hundred soldiers out of what had been at least a 3000 man party. Byzantine writers joked (?) that he rode off flinging coins behind him to try to distract his pursuers.

The destruction of his army, as well as the sudden onset of some debilitating medical problems, meant that Sayf al-Dawla could do little when Nikephoros returned victorious from Crete and brought the full weight of the Byzantine army south through Cilicia and along the eastern Mediterranean coast. That army defeated the Hamdanids at Aleppo in 963 but carried off booty rather than trying to occupy the city. Nikephoros had to return north when Romanos died later that year, but once he’d become emperor himself he resumed Byzantine operations in the region—in fact, by the time of his assassination in 969, he’d conquered the city of Antioch and reduced the once-mighty Hamdanids of Aleppo to the status of imperial vassals. The Byzantines, meanwhile, continued their resurgence under the “Macedonian dynasty.” That resurgence had about another century to go before the Seljuks snuffed it out.