Today in Middle Eastern history: the Ottoman coup of 1807

Sultan Selim III's attempt to marginalize the Janissary Corps backfires, to put it mildly.

If you’re interested in history and foreign affairs, Foreign Exchanges is the newsletter for you! Sign up for free today for regular updates on international news and US foreign policy, delivered straight to your email inbox, or subscribe and unlock the full FX experience:

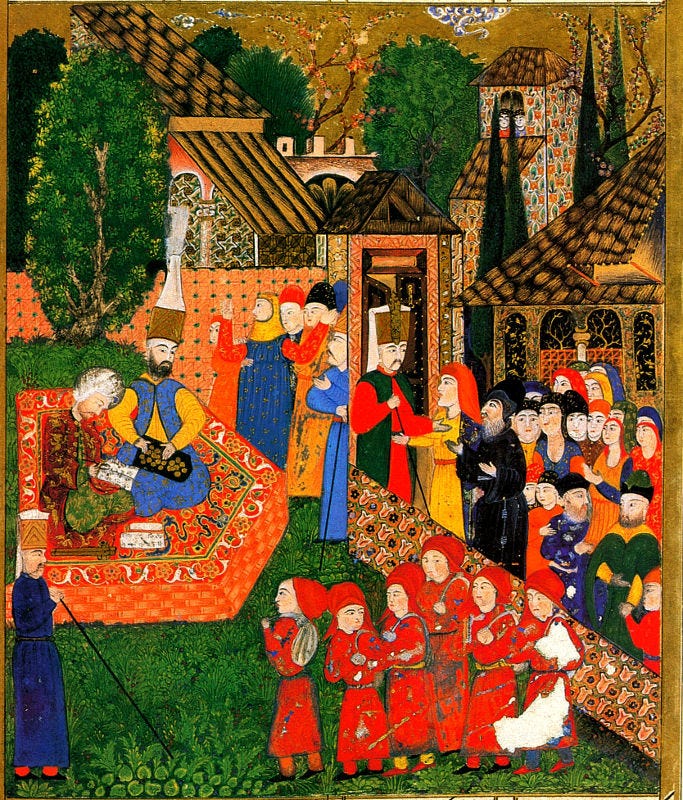

The May 29, 1807 coup that overthrew Ottoman Sultan Selim III (d. 1808) and replaced him with his cousin, Mustafa IV (also d. 1808, which should give you some idea where this is going to wind up), isn’t a major event in Ottoman history, certainly not on par with what happened on this date in 1453. But it does mark the failure of the first of several Ottoman “reform” periods that marked the empire’s history in the 18th and 19th centuries, and highlights one of the main obstacles to those imperial modernization efforts.

I’m talking here about the corruption and degradation of the Janissary Corps, which had once been the most capable and most feared fighting force in Europe. It’s not clear when exactly the Janissary Corps was formed, but we know it was established as a royal bodyguard as early as the reign of Murad I (1362-1389), who expanded the empire into the Balkans and was the first Ottoman ruler to take the title “Sultan.” The Janissaries were “recruited” via a program known as the devşirme (“devshirmeh”), a “draft” imposed mostly (there were a few exceptions) on Balkan Christian families living under Ottoman rule.

Pre-adolescent boys were taken from these families, converted to Islam, taught the Turkish language, and put to work as what were technically slaves, or kul (though they were generally better treated than, say, the average household slave). You can imagine that the devşirme was not especially popular among the families of those who were drafted. But there was an upside to the arrangement, in that a very successful product of the devşirme could rise through the Ottoman bureaucracy and even (in theory) become Grand Vizier, officially the second-most powerful person in the empire behind the sultan himself.

Once they’d been conscripted, the young slaves were trained in a variety of forms of state service, from working on the sultan’s household staff to serving in the bureaucracy to serving in the military, where they made up the Janissary Corps (from the Turkish yeniçeri, or “new soldier”). As a fighting force they had a lot going for them: high unit cohesion (since they all came from similar backgrounds and grew up together), high levels of training (facilitated by the fact that this was a professional standing army that could train even in peace time), and the best weapons and equipment available (owing to the empire’s wealth). The corps quickly became expert in using gunpowder weapons, from heavy siege guns to personal firearms, and they were more than a match for the empire’s enemies, from Europe to Iran to Egypt.

As a nod to the risk that such a powerful standing army posed to the empire itself, Janissaries were prohibited from owning businesses and their children were forbidden from serving as Janissaries themselves. That way they couldn’t enhance their power through economic means and the empire didn’t have to worry about a hereditary military class becoming an independent political force.

In hindsight it’s easy to see that a system like this is impossible to sustain indefinitely, and there are two big reasons why. First, a military empire that invests the kind of resources and power in a particular unit that the Ottomans invested in the Janissaries is empowering that unit politically, like it or not. The Janissaries realized in the 16th and 17th centuries that they didn’t have to obey restrictions on their involvement in the economy (owning their own businesses, for example) because no other imperial authority could make them. On the contrary, they began to get very rich and very contented, which meant that they were less keen on training and drilling and fighting all the time. Again, who was going to make them? As we’ll see, nobody. At least not yet.

Second, the Ottomans made the Janissaries too appealing to keep non-Muslims out. Service in the Janissary Corps, via the devşirme system, was the only real path to high status in the Ottoman bureaucracy, and the Ottoman bureaucracy was one of the most reliable imperial paths to long-term personal success and wealth accumulation (as long as you had no problem doing things that, at least nowadays, would be regarded as outrageously corrupt). This created a powerful set of incentives for those who were technically locked out of the devşirme (Turks, other Muslims, children of Janissaries) to find a way into the system. In the late 16th century, imperial officials opened the devşirme class up to other imperial subjects, to the great detriment of that unit cohesion I mentioned earlier. Overall the number of Janissaries ballooned, but their training and equipment (it became prohibitively expensive to outfit and train tens of thousands of men with the latest hardware) declined precipitously.

The general weakness of Ottoman sultans in the late 16 and 17th centuries didn’t help, as they were unable to serve as a counter to the growing power and corruption of the Janissaries. This weakness can partly be traced to a change in the manner of succession. Succession in the Ottoman dynasty had been managed via what can arguably be described as fratricide by civil war. The Ottomans didn’t institute a firm succession principle like primogeniture, and in fact as Turks their traditions dictated that inheritance pass to all the sons of the deceased (steppe traditions aren’t necessarily compatible with ruling an empire). Ottoman princes would be sent to govern provinces and command their own military units to prepare them to be emperor, and then they and their loyal soldiers would often fight it out among themselves to see who would succeed their father. This is, to say the least, an incredibly inefficient way to pick a new emperor, but it does mean that whoever winds up succeeding to the throne will be trained, probably have a strong interest in running the empire, and, more often than not, will be the best military commander of the lot.

Under Sultan Ahmed I (d. 1617), these policies were changed so that only one prince, the chosen heir, would serve in some kind of governorship to prepare him for the sultanate. The rest of the princes were confined to the palace (a system literally called “the cage,” or kafes) in order to render them powerless and to eliminate the need for all these destructive civil wars. Some princes still had their brothers killed upon succession, just to be safe, but from this point on that just involved straight up murder rather than civil wars.

The big problem here is that it quickly became more advantageous for a prince to be confined to the palace than to serve in the provinces. In the palace, a prince could play backroom politics with the bureaucrats, often with the support of his mother, who would obviously love the chance to become the valide sultan (queen mother) and would put her own political skills toward that end. Where the empire had been producing heirs with training and military skill, now it began producing heirs whose biggest asset was their ability to ingratiate themselves with the palace bureaucracy, and whose capacity to actually run the empire, to say nothing of their interest in running it, was often negligible.

Selim III took the throne in 1789 upon the death of his uncle Abdülhamid I, who seems to have been a nice guy but led the Ottomans into a couple of disastrous wars with Russia and was powerless to fix the problems with the Janissaries (in his defense, he was hamstrung by the fact that this once extravagantly wealthy empire was by this point struggling with a nearly empty treasury). In contrast to a century plus of addled and/or weak sultans, Selim knew what needed to be done and was prepared to do it. His father, Sultan Mustafa III (d. 1774), had been well aware of the need for military reform (though he was powerless to implement it against opposition from the Janissaries) and probably passed that on to his son.

Selim took the throne with the empire already mired in (losing) wars with Russia and Austria, so he had no time to attempt any reforms until later on in his reign. He resolved to build an entirely new force rather than reform the bloated Janissaries, and so he instituted new taxes to pay for it and then brought in experts from all over Europe to train and equip it. He called his reform program, heavily influenced by what Napoleon was doing in France, the Nizam-ı Cedid, Persian for “the new order.” The new army was at the heart of the reform, though creating that new army also required things like comprehensive school reform (for training) and a strengthened bureaucracy (to manage the processes of equipping and paying the new soldiers).

These were defensible moves (and the new army acquitted itself well in defending Acre from Napoleon in 1799, for example), but they managed to piss off just about every major stakeholder in the empire. The Janissaries feared, rightly, that this new military force was going to render them obsolete. The empire’s other military power, the major landowners who were given military fiefs to rule in exchange for supplying troops (usually cavalry), hated the reforms because they were partially financed by confiscation of their fiefdoms. And the religious establishment was angry because the reforms were being implemented along European models and were also partly being paid for through new taxes that were deemed impermissible under Islamic Law.

When these elements all approached Abdülhamid I’s son, the future Mustafa IV, about deposing Selim and putting him on the throne instead, they found a willing partner and the deed was done without much fuss on this date in 1807. The aftermath took a little while to unfold, but it didn’t work out very well for either the new sultan or the man he overthrew. One of Selim’s governors, Alemdar Mustafa, assembled an army of 40,000 men and, in July 1808, was marching on Istanbul to reinstate Selim when Mustafa decided to have his predecessor killed to forestall that possibility. He also ordered that his own brother, the future Mahmud II, be killed, which would have made Mustafa literally the last surviving Ottoman male and thus untouchable. But Alemdar Mustafa got to Istanbul before that happened, executed Mustafa IV, and put Mahmud on the throne, where he would stay until his death in 1839.

Although Selim didn’t get to see it, the Nizam-ı Cedid ultimately got the last laugh. After continuing Selim’s work, albeit a bit more carefully, on June 15, 1826 Mahmud II took advantage of a Janissary revolt in Istanbul to break the Corps once and for all. He rallied residents of the city (most of whom hated the Janissaries by now) to his cause and ordered the new army, called the “Victorious” or Mansure Army, to bombard the Janissary barracks. Known as the “Auspicious Incident,” this event left thousands of Janissaries dead and thousands more captured (most were later executed). The Janissary Corps was no more, and Ottoman military fortunes actually ticked up for a while even as forces of nationalism and economic weakness continued to drag the empire as a whole toward its end.