Today in Middle Eastern history: the Surrender of Kut (1916)

One of the worst military defeats in British history leads to one of World War I's most notorious atrocities.

If you’re interested in history and foreign affairs, Foreign Exchanges is the newsletter for you! Sign up for free today for regular updates on international news and US foreign policy, delivered straight to your email inbox, or subscribe and unlock the full FX experience:

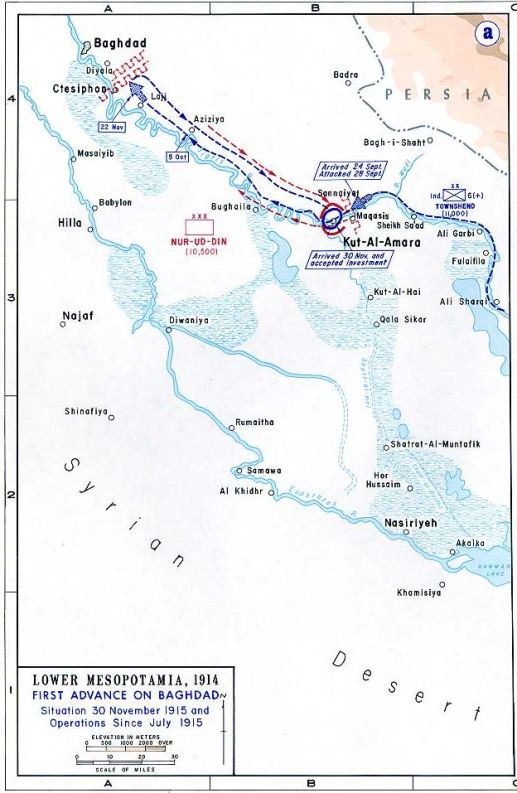

Today is the anniversary of one of the worst military fiascos in British history, the surrender of the 6th division of the Indian Army to the Ottomans at the Iraqi town of Kut. The surrender followed right on the heels of the Battle of Ctesiphon in November 1915, turning that tactically indecisive battle into a major strategic Ottoman victory.

The engagement that led up to Kut was part of a poorly conceived and even more poorly managed British offensive whose goal was to capture Baghdad. In short, a fairly undermanned British army of around 12,000 or so men, under General Charles Townshend, marched into central Iraq, stretching its supply line too thin in the process, and then encountered much tougher than expected Ottoman resistance. With the Ottomans able to get reinforcements and supplies to the front much easier than the Brits could, they had little trouble isolating and eventually crushing Townshend’s force.

Ctesiphon was the first heavy engagement of the offensive, and it ended in a tactical stalemate, as both the British attacking force and the Ottoman defenders took heavy losses and ordered a retreat on the final day of the battle. While neither side got the better of the fighting, the British attackers were in the much more challenging situation given their supply challenges. The Ottoman commander, Nureddin Ibrahim Pasha, quickly realized this and turned his somewhat larger army (it had been around 18,000 soldiers strong before Ctesiphon) around to pursue the enemy. Townshend, for reasons I assume made sense to him at the time, opted not to make a beeline back to British territory and instead chose to hole up at Kut and await reinforcements.

In fairness, it seems Townshend believed that he had to try to pin the Ottomans down at Kut to keep them from attacking British positions further south, but this was a clear miscalculation. Just as Townshend’s northward march had exposed the weakness of British supply lines, logistically the Ottomans couldn’t possibly have undertaken an offensive in southern Iraq without leaving themselves similarly exposed. Townshend also believed that Kut was defensible and that British control over the Tigris River would allow them to ferry reinforcements north to bolster his forces. On these points he was, as it turns out, also completely wrong.

The Ottomans, now under the command of German Field Marshal Colmar Freiherr von der Goltz, who had arrived to relieve the less experienced Nureddin Pasha, besieged Kut on December 7, 1915, and over the course of the next four-plus months drove off three separate major British overland relief attempts and managed to prevent most British ships from getting upriver. In a last-ditch attempt to save the army, Britain sent representatives, including T.E. Lawrence (who wasn’t quite “Lawrence of Arabia” yet) to negotiate a ransom payment to the Ottomans. The Ottomans rejected any payment, and Townshend was left with no choice but to surrender.

By the end of the siege, between Townshend’s losses and the various failed relief expeditions, the British had lost somewhere between 20,000 and 30,000 soldiers. Ottoman losses were considerably lighter, though Field Marshal von der Goltz was among them, having succumbed probably to typhus. The Ottoman commander of Baghdad, Halil Kut, relieved him and brought an extra 20,000 men to bolster the siege, which came in handy in running off those British expeditions. It was both the largest British military defeat and the longest siege in history at the time, though it would be eclipsed on both accounts during World War II. And it was only going to get worse. The last thing I wanted to highlight was what happened to Townshend and his men after the battle, because it’s really a microcosm of the entire war.

World War I was the archetype of meat-grinder warfare. The Gentlemanly Class, whose members all wound up serving as officers regardless of merit, felt no particular misgivings about sending thousands upon thousands of riff-raff (who were all stuck in the lower ranks, of course) off to be brutally slaughtered in operations that were poorly planned (why spend a lot of mental energy planning an operation when it’s only privates who are going to get killed if it goes sideways?) and that frequently wouldn’t have gained much even if they’d been tactically flawless.

Townshend was certainly one of these Gentleman officers, and his army included a large number of Indian soldiers who were deemed even more expendable than enlisted men from the lower classes of British society. Maybe that explains why it doesn’t seem to have fazed him in the slightest that he and his top officers were all ferried upriver by boat and on to Istanbul—where Townshend was treated as a foreign dignitary and became good friends with Ottoman Minister of War (and the most powerful man in the empire) Enver Pasha—while his men were death-marched overland to prison camps in Anatolia. Somewhere in the neighborhood of 12,000-13,000 British soldiers surrendered to the Ottomans during the siege of Kut, and of those fully a third of them died either on the march or in the camps. As far as anybody knows, Townshend asked after the condition of his men exactly once, and having not gotten a straight answer from the Ottomans, never asked again.

Townshend remained in luxurious “captivity” in Istanbul for the rest of the war. Simply by virtue of his presence in the Ottoman capital, he had a hand in negotiating the Ottomans’ military surrender to Britain in 1918, which he later (without merit) claimed was entirely his doing. He finally returned home and was stunned to find that he wasn’t given a hero’s welcome, then stunned again when the British Army told him that his services were no longer required. The British government wanted to try Enver Pasha for war crimes, mostly over the Armenian Genocide but also in part over the post-Kut death march, but Townshend, astonishingly, denied that the march ever took place (how would he have known?) and said he would testify in his pal Enver’s defense. Incredibly, or maybe predictably, he was elected to Parliament after he left the army, though to be fair to the voters this was before the details of his military service had really been investigated.