Today in Middle Eastern history: the Iranian Revolution ends (1979)

The remnants of the Iranian monarchy finally collapse and the Islamic Republic begins to emerge.

If you’re interested in history and foreign affairs, Foreign Exchanges is the newsletter for you! Sign up for free today for regular updates on international news and US foreign policy, delivered straight to your email inbox, or subscribe and unlock the full FX experience:

Right off the bat I should note that today’s post is somewhat ahistorical. February 11 is generally considered the anniversary of the Iranian Revolution, and I’m not sure I agree with that. The date is not insignificant—it was on February 11, 1979, when the royal Iranian army surrendered, marking the end of organized resistance to the revolution, which is an important milestone. But I’m not sure why it’s a more important milestone than the shah’s departure from Iran (January 16), the dissolution of the regency council he left to run the country in his absence (January 22), Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini’s return from exile (February 1), the creation of the Islamic Republic (March), or the adoption of its constitution (December). Really everything after the shah’s flight out of Tehran took off seems a little anticlimactic.

Nevertheless, February 11 is considered the anniversary of the revolution for those who like to put one single date on things. So I guess we should note that. I've done a lengthy podcast series about the revolution that's in the archives, if you’re a subscriber, so I don’t want to go into fine detail about the revolution here and duplicate that. A full accounting of the Iranian Revolution is far too much for one post anyway. But since we’ve already covered Khomeini’s triumphant return to Iran, I thought we’d focus here on the events that led to it and to the surrender of the royal army ten days later.

The causes of the Iranian Revolution run all the way back to the 1953 coup that overthrew the government of Mohammad Mosaddegh—or really, if you want to be comprehensive about it, all the way back to the late 19th century and a growing popular and religious sentiment that Iran’s rulers were too corrupt, too compromised by the West, and/or too secular to legitimately run the country. A century of repeated British and then US interventions in Iranian affairs added to the growing sense of outrage. Resistance to the increasingly authoritarian Mohammad Reza Shah Pahlavi and anger over Iran’s broken economy were the main immediate triggers.

But if we’re going to pick a specific start date, again for those who like these things to be tidy, then the one most often cited is January 7, 1978. On that day, Iran’s Ettelaʿat newspaper ran a piece ridiculing Khomeini in extremely derisive terms (among them was the accusation that he was a “British agent,” which is pretty wild coming from a newspaper supporting the shah). Khomeini’s son, Mostafa, had recently died under highly suspicious circumstances in Najaf, Iraq—the theory that agents of the shah’s SAVAK secret police murdered him is widely accepted in Iran to the present day. So the editorial added to a sense that Khomeini was being targeted by the Iranian regime, and it was enough to cause seminary students in the city of Qom to riot.

Obviously the Shah couldn’t have known it at the time, but those riots marked the beginning of the end for his reign. Two people were killed by Iranian police, and 40 days later (the end of the traditional mourning period in Shiʿism) on February 18, protests broke out again, only this time in several major Iranian cities. Six people were reportedly killed in those demonstrations, and at the next 40 day mark (March 29), the protests went nationwide. The pattern repeated itself again in another 40 days, on May 10, and every 40 days for most of the rest of the year, though after the May 10 protests the crowd sizes at subsequent events began to level off or even diminish a bit.

The Shah reacted to these protests with something approaching total bewilderment. He clearly hadn’t seen the tension building up in Iranian society, and when it exploded his response was indecisive. He already believed he was under pressure from US President Jimmy Carter to curb his human rights abuses and authoritarian tendencies (he was not, actually, but he’d become a little paranoid by this point). So in order not to lose support in Washington, he opted not to respond with all-out violence. But neither did he offer what the protesters seemed to want, which was an immediate return to governance according to the principles of the 1906 Iranian constitution. Instead, the Shah promised to continue slowly liberalizing the Iranian political system as he’d been doing for the previous few years, scheduling a parliamentary election for sometime in 1979. This clearly wasn’t good enough, as far as the protesters were concerned. Meanwhile, though official policy was to use a light touch with demonstrators (those who were detained were to be quickly released), the shah’s security forces kept killing people anyway, either due to a lack of training and proper equipment or for more sinister reasons.

Still, things did start to calm down. The experts at the CIA determined that there was no risk of a full revolution in Iran and Washington relaxed accordingly. But the demonstrations kicked back into high gear in August, bolstered by large working class and merchant participation. Then, on August 19, terrorists locked the doors to a movie theater in Abadan and set the place on fire. They killed 422 people. I say “terrorists” because it seems like the right term and because there’s still no consensus as to who they were. Revolutionary leaders, including Khomeini from exile, blamed the Shah and SAVAK for the fire, but there’s a fair amount of evidence to suggest they were revolutionaries of some stripe and possibly Islamists. Growing desperate, the shah named Jafar Sharif-Emami as his new prime minister, mostly because Sharif-Emami was known to be close to Iran’s religious community.

Sharif-Emami quickly set out to basically reverse the last 5-10 years of Iranian policymaking, undoing anything the Shah had proposed that had any whiff of unpopularity about it. He dissolved the Resurgence Party, the only legal political party in the country. He began firing SAVAK bosses left and right. He released political prisoners. He ended official censorship and cracked down hard on official corruption. It was all too little, too late, and at this stage actually seems to have emboldened the revolutionaries by showing them how desperate the regime had become.

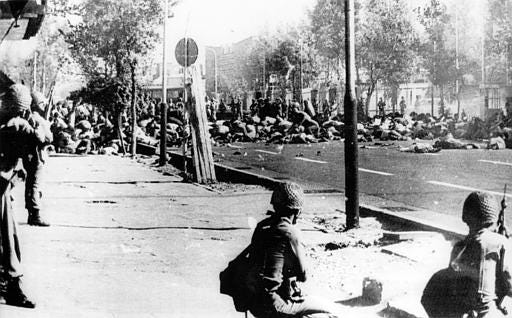

With protests still growing, the shah now lurched in the direction of repression, declaring martial law in several cities, including Tehran, at midnight on September 8. Later that day, thousands of people turned out in Tehran’s Jaleh Square, either unaware of or unfazed by the declaration. Police and soldiers met them in the streets and a bloodbath ensued. The government officially acknowledged that somewhere in the neighborhood of 88 people were killed, some of them police but most of them protesters, while opposition leaders cited figures in the thousands, and most of the Iranian public believed the latter. The shah promptly lurched back in the other direction and ordered his security forces to stop breaking up protests, despite the fact that much of the country remained under martial law. Jomʿe-ye Siyahi, or “Black Friday,” as the day became known, marks what many consider to be the “point of no return” for the revolution. From then on, even protesters who had merely been calling for reform and a return to the 1906 constitution began demanding unequivocally that the Shah must go.

At this point, Khomeini moved his exile (he’d been out of the country since 1964) from Iraq to France—with the strong blessing of Iraq’s Baathist government, whose leaders loathed Khomeini’s Islamist politics and were happy to see him go. In France, Khomeini quite skillfully portrayed himself to Western media as a freedom fighter and saw his prestige really take off among Iranians of all backgrounds. It’s in France where he became the de facto leader of the revolution. Leaders from the secular National Front, the movement that Mosaddegh had formed back in the late 1940s, visited him in France to begin making plans for a post-Shah Iran. The Shah, pretty much panicking at this point, dissolved Sharif-Emami’s government on November 6 and appointed a military government in its place. In a speech announcing the change, the shah apologized for errors he’d made and pledged his support for the revolution and its ideals. Again this had the effect of emboldening, rather than appeasing, the revolutionaries. It was also a literal lie, since the revolution’s main ideal was getting rid of the Shah and at this point he still had no plans to step down.

The protests hit their peak in December, during the Islamic month of Muharram. It's believed that upwards of 10 percent of the Iranian population turned out on Ashura (December 10 and 11) to demand the shah’s removal and the return of Khomeini, which according to people who study revolutions is a stunning figure that vastly exceeds the level of turnout that the French or Russian revolutions, for example, can boast. By this time the movement to oust the shah crossed nearly every Iranian social class apart from the royals themselves, and it was still ideologically amorphous enough to appeal to just about everyone. In particular, at this point there was nothing to indicate that the revolution would take the heavily Islamist course we now know it took. Though Khomeini was clearly the central figure for the revolutionaries, many believed he would remain merely a symbolic totem and let the real work of rebuilding and governing the new Iran be done by secular politicians. Oops.

As 1978 became 1979, the shah’s time on the throne was running out quickly. On December 7, he learned that the leaders of the US, UK, France, and West Germany were planning to meet in early January to discuss what to do about The Crisis In Iran, and he assumed they were going to talk about how best to abandon him to the revolutionaries. Then reports began to trickle in that senior Iranian generals were starting to meet with opposition leaders, and that was probably the final straw.

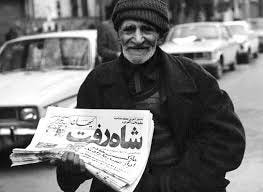

In late December, the shah cut a deal with National Front politician Shahpour Bakhtiar whereby Bakhtiar would take over as prime minister and the shah would go into a self-imposed exile, leaving a council in place to carry out royal duties. This happened on January 16, but Bakhtiar was basically dead on arrival with the Iranian public, who perceived him not as an opposition leader who’d been handed power by the hated outgoing ruler but as the shah’s last prime minister and therefore his conduit for continuing to rule Iran by proxy. The chair of the new royal council, meanwhile, hopped a flight to France and presented his resignation to Khomeini. The symbolism of that act would have been pretty hard to miss.

Bakhtiar invited Khomeini to return, and it quickly became apparent that not only was Bakhtiar’s term as PM going to be extremely short-lived, but that Khomeini had no intention of letting anybody else control Iran’s destiny. Khomeini set up his own Iranian government, under Mehdi Bazargan, on February 5, and violence ensued. The Iranian military, under Bakhtiar’s control, battled a cacophony of rebels including street protesters, leftist guerrilla fighters, and elements of the Iranian military that defected over to the Khomeini/Bazargan side. The rebels clearly had the upper hand, and so to avoid additional bloodshed the Iranian military declared itself politically neutral on February 11 and its soldiers withdrew to their barracks, effectively surrendering to Khomeini’s forces. One phase of the revolution was over, but there was much more to come over the next several months.