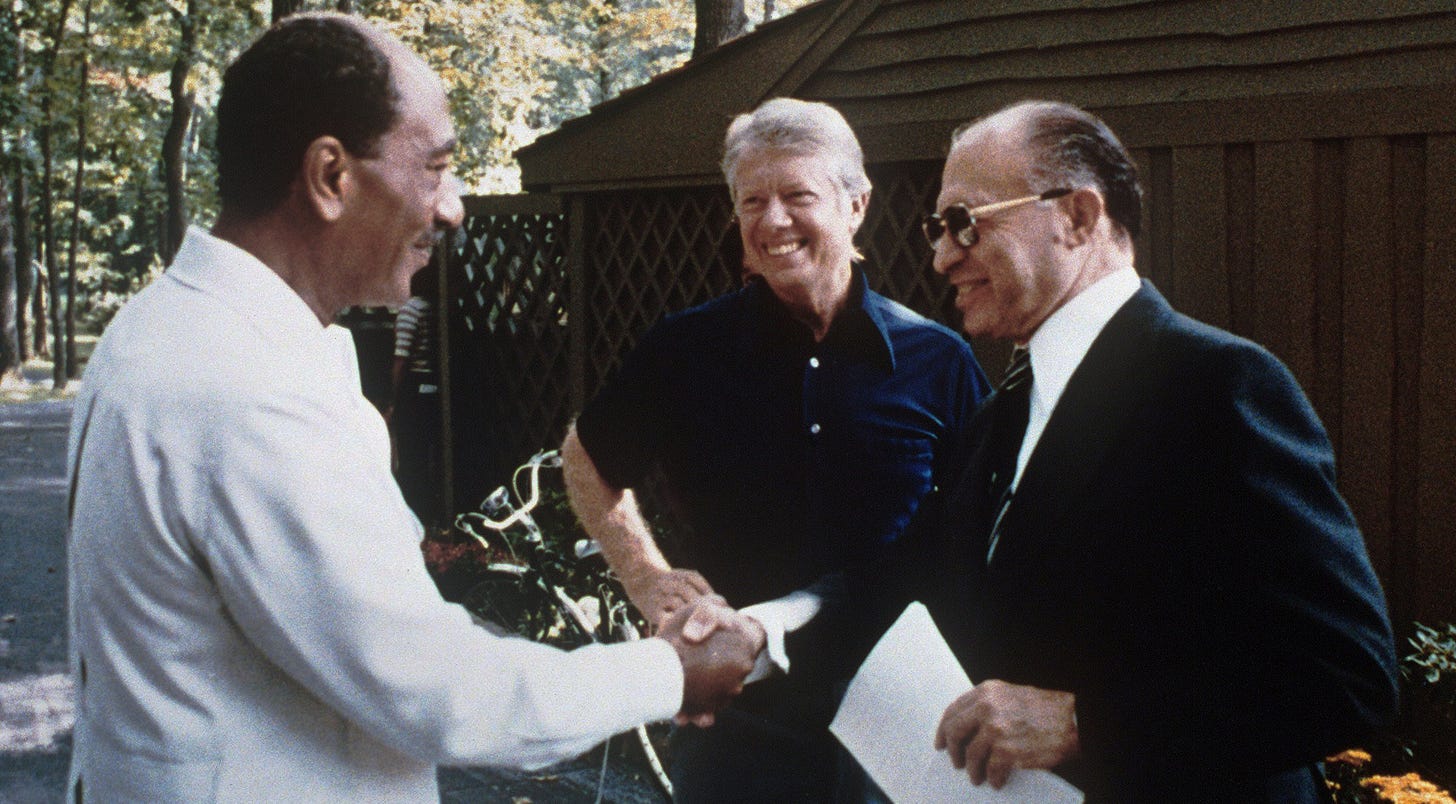

Today in Middle Eastern history: the Camp David Accords (1978)

Egypt becomes the first Arab state to normalize relations with Israel, in a deal brokered by US President Jimmy Carter.

If you’re interested in history and foreign affairs, Foreign Exchanges is the newsletter for you! Sign up for free today for regular updates on international news and US foreign policy, delivered straight to your email inbox, or subscribe and unlock the full FX experience:

A few days ago we passed the anniversary of the Oslo I Accord, US President Bill Clinton’s attempt to foster a durable Israeli-Palestinian peace accord that turned out instead to be a lopsided, unworkable framework that’s fostered nothing but many years of failure and frustration. Today we mark the anniversary of Oslo’s closest antecedent, the Camp David Accords. These began as US President Jimmy Carter’s attempt to foster a durable Israeli-Arab peace accord and ended with the framework for a treaty between Israel and Egypt and, well, that was about it. But that was still a pretty significant accomplishment.

The roots of the Camp David Accords and the subsequent Egypt-Israel Peace Treaty lay in the 1973 Yom Kippur War. The opening for peace talks was created by the peculiar outcome of that war—a tactical Israeli military victory that was nevertheless treated by the defeated Egyptians as a strategic victory and by the victorious Israelis as a strategic defeat. The Egyptians began the 1973 war with a sudden attack, Operation Badr, that set the Israeli military back on its heels, and it took more than a week for the Israelis to collect themselves and change the tide of the war. And the outcome left Egypt in physical control of both banks of the Suez Canal, recovering the eastern bank they’d lost to Israel in the 1967 Six Day War. That may not seem like much of a win, but for a country that had been thoroughly humiliated by Israel in 1948 and again in 1967 it was huge.

Although they were relatively minor achievements, the initial success of Operation Badr and the final recapture of the eastern bank of the Suez restored Egyptian national pride. Egypt came out of the war with its collective head held high, having shown that it could bloody the Israelis on the battlefield and therefore that it was Israel’s equal, or something like that. And yes, that’s pure symbolism, but in this case the symbolism allowed Egyptian President Anwar Sadat to engage in diplomacy with Israel without losing support domestically. This was good news for the Egyptians and fantastic news for the United States, which was in the process of enticing Sadat away from the Soviets and bringing Egypt, the largest and at the time most powerful Arab state, into the US camp. But that process could only be fully completed if Egypt and Israel, by this point a close US ally, made nice with one another.

When Jimmy Carter came into the White House in 1977, he had a mind to make Arab-Israeli peace one of his big projects. In order to achieve this, he looked to build on the diplomacy that Henry Kissinger (I know, I know) had conducted both to conclude the 1973 war and then in its immediate aftermath. Kissinger (believe me, I know) really gets a good deal of the credit for the US-Egypt rapprochement, though in some respects he was responding to signals from Sadat, who was growing uncomfortable with the degree to which Egypt had become dependent on the Soviets. In particular, without the work Kissinger did convincing the Israelis not to destroy Egypt’s Third Army, which it had completely surrounded in the Sinai toward the end of the war, none of this subsequent diplomacy could have taken place. The survival of that army was a huge gift for the Egyptians and went a long way toward allowing them to pretend that they’d won the war (or at least held their own). Beyond that, it gave Kissinger his diplomatic opening into Sadat’s government.

Kissinger used that opening to negotiate not only the ceasefire agreement that ended the war, but two agreements between Israel and Egypt in the months following the war, both having to do with the disposition of military forces in the Sinai. In January 1974 he brokered the Sinai Separation of Forces Agreement, or “Sinai I,” under which the Israelis agreed to pull back from the canal so as to set up a buffer zone between Egyptian and Israeli forces. Then in September 1975, Kissinger brokered the Sinai Interim Agreement, or “Sinai II,” under which Israel agreed to withdraw still deeper into the Sinai. Again, despite having technically lost the war, Egypt regained a third of the Sinai, lost to Israel back in 1967, under these agreements.

So the precedent for this kind of “land for peace” diplomacy between Israel and Egypt was already set when Carter took office. Carter saw a chance to make “land for peace” the framework for a general accord between Israel and all of its Arab neighbors—Egypt again (the rest of Sinai and Gaza), but also Jordan (the West Bank) and Syria (the Golan). He spent 1977 meeting with leaders of all four nations to get them on board with a regional peace process that would be mostly conducted via conference in Geneva. Syrian President Hafez al-Assad told Carter to get bent, and King Hussein of Jordan also passed due to concerns that he might alienate other Arab leaders (Assad in particular) by participating and also because, just between you and me, I’m not really sure Hussein wanted to be responsible for the West Bank again.

This was all fine by Israeli Prime Minister Menachem Begin, who was wary of a regional initiative, didn’t want to give up the West Bank, and had been quietly talking with Sadat (who was also wary of Carter’s regional agenda) about a bilateral arrangement anyway. Their talks culminated with Sadat visiting Israel and delivering a speech before the Knesset in November 1977, which kicked off the three way diplomacy that led to Camp David. Sadat, who had come to believe that Carter’s Geneva process was a mirage and that his insistence on an unattainable regional peace was standing in the way of a very attainable bilateral accord, viewed the process as a way to get back the Sinai and cement ties with the US. Begin saw a way to make a peace deal with the leading Arab state by giving up land Israel didn’t really want anyway, scuttling the Geneva initiative to boot.

Carter was initially cool to the idea of brokering Egypt-Israel peace talks because he knew full well that they would scuttle the Geneva process. But it’s not like he could stop Israel and Egypt from talking, and ultimately he came, perhaps by way of some wishful thinking, to see their arrangement as a stepping stone to a regional deal. He agreed to bring Sadat and Begin to Camp David on September 5, 1978, for what was 13 days of talks wherein Carter had to play messenger between two men who wanted to negotiate but couldn’t really stand one another on a personal level. The result was two agreements, “A Framework for Peace in the Middle East” and “A Framework for the Conclusion of a Peace Treaty between Egypt and Israel.” Only the latter had a prayer of going anywhere.

“A Framework for Peace in the Middle East” was an attempt to shoehorn in Carter’s idea for a regional peace plan despite the fact that, you know, nobody else from the region was involved in its creation. It provided for hypothetical Palestinian autonomy within five years and talks between Israel, Egypt, Jordan, and the Palestinians on establishing a Palestinian “authority” in the West Bank and Gaza. As it was negotiated with no Palestinian input and said nothing about Palestinian independence, the right of return, etc., it was rejected by the United Nations General Assembly, to say nothing of the Palestinians themselves or the Jordanians, who were in actuality pretty offended that Sadat had committed to a peace process on their behalf. Elements, though, like the aforementioned “Palestinian authority,” did stick around through Oslo.

“A Framework for the Conclusion of a Peace Treaty between Egypt and Israel,” on the other hand, was a much more straightforward agreement and was the one that everybody at Camp David, not just Carter, wanted to conclude. In essence, Israel agreed to give the Sinai back to Egypt (with restrictions on Egypt’s military presence there) in return for normal diplomatic relations between the two countries. The US committed to significant long-term aid packages for both countries, mostly military aid which had the effect of boosting defense contractors’ bottom lines and of fully weaning Egypt away from the Soviets. Around six months later, in March of 1979, the “Framework for the Conclusion of a Peace Treaty between Egypt and Israel” gave way to an actual peace treaty between Egypt and Israel, signed at the White House.

You know how excited the US and Israel were to make friends with Egypt, the most powerful and influential Arab state? Well, about that. Sadat wound up surrendering most of said influence in order to make this deal. Egypt was suspended from the Arab League until 1989 and the leadership vacuum it left in the Arab world became a prize over which Assad, Saddam Hussein, and the Saudis fought for the next 15 years or so (SPOILER ALERT: the Saudis won). Sadat himself rode the wave of popular revulsion to his peace deal straight to his 1981 assassination at the hands of Egyptian Islamic Jihad. Despite the hit he (and Egypt) took, though, Sadat’s example informed other regional leaders, and it’s unlikely that Oslo or the 1994 Israel-Jordan peace treaty—or the more recent agreements Israel has reached with the UAE and Bahrain—would have happened had Camp David not paved the way.