Today in Middle Eastern history: the Battle of Manzikert (1071)

In one of history's most consequential battles, the Seljuk Turks breach the Byzantine Empire's core and begin the Turkish conquest of Anatolia.

If you’re interested in history and foreign affairs, Foreign Exchanges is the newsletter for you! Sign up for free today for regular updates on international news and US foreign policy, delivered straight to your email inbox, or subscribe and unlock the full FX experience:

For some reason the end of August/beginning of September is a busy season for major battles in Middle Eastern history, like Yarmouk, Chaldiran, and Marj Dabiq. There’s another one coming in a couple of days and another a few days after that, but we’re getting ahead of ourselves. You could argue that of all of these major battles, Manzikert is the most significant. Although it took another 400 years to finally come to fruition, it was the Battle of Manzikert that set in motion the collapse of the Byzantine Empire. Which, if you think about the Byzantines as a continuation of the Roman Empire, means it dealt a mortal blow to a political entity that survived for almost 1500 years (and even longer if you include the Roman Republic before that). That’s pretty significant.

After Yarmouk, you may recall, the Byzantines retreated to the opposite side of the Taurus Mountains, which separate Anatolia from the Syrian plains to the south. They relied on those mountains, plus the Caucasus in the east, to protect them from Arab/Muslim invaders. For the most part, this strategy worked. Yes, various Islamic armies did invade Anatolia a few times and even besieged Constantinople on a couple of occasions, but keeping an army supplied for an extended stay on the other side of the mountains invariably proved impossible. The terrain was too challenging and Byzantine border skirmishers were too effective, and Constantinople’s walls would eventually suck the life out of any siege. So the Byzantine Empire carried on, and even thrived at times, albeit at a drastically reduced size compared with what it had been in, say, the sixth century.

By the 11th century, military power in the Islamic world (east of Egypt, anyway) had shifted from the Arabs to a few Iranian dynasties and then to Turks, specifically the Seljuk Turks. The Seljuks claimed descent from a branch of the semi-mythical Oghuz family, the same Turkic family from which the Ottomans and many other Turkic groups claimed descent. I say “semi-mythical” because the Oghuz were definitely a real tribal grouping, but the stories told about their origins were mythical, or at least they can’t be substantiated as historical. The Seljuk invasion/migration is considered the first “wave” of Oghuz movement out of Central Asia and into the Middle East. The second wave, if you’re wondering, happened in the 13th century—not in an organized fashion, but as Turkic tribes fled west ahead of the oncoming Mongols.

After converting to Islam sometime in the 10th century, the Seljuks swept through Iran and Iraq in the early 11th century. Along the way, they “liberated” the Abbasid Caliph in Baghdad. Let me explain. In 945 the weakened Abbasids, who were already mostly governing at the whims of their Turkish slave soldiers, had fallen under the “protection” of the Iranian Buyid dynasty from the southern Caspian region. In practice this “protection” meant that the caliphs retained their titles and theoretical authority, but the Buyids ran the caliphate. The Buyids were Shiʿa, and though they never tried to impose Shiʿism on the rest of the empire, the Abbasids appear to have welcomed it when the Sunni Seljuk ruler Tughril Bey (d. 1063) drove the Buyids out of Baghdad in 1055. Of course, instead of restoring the caliphs to real power, the Seljuks simply replaced Buyid “protection” with their own. The Seljuks then turned most of their attention toward the rival Fatimid Caliphate in Egypt. But they also had to worry about the possibility of a Byzantine attack in their rear while they were preoccupied with the Fatimids (the Byzantines and the Fatimid Caliphate were on good terms with one another), so the Caucasus in particular were an area of interest for them.

The Byzantines, meanwhile, were in the middle of a few decades’ worth of inter-dynastic turmoil following the end of the supremely successful Macedonian Dynasty. Emperor Michael IV died in 1041 and his successor, Michael V, was assassinated the following year. This brought Constantine IX (also known as Constantine IX Monomachos) to power, alongside the empresses Zoe (who married Constantine IX) and Theodora, who were the daughters of Constantine VIII and thus had their own (competing) claims on the throne.

This triumvirate focused more on domestic matters than it did on defending the empire’s borders, and it showed. During Constantine IX’s reign, the Normans drove the Byzantines almost completely out of Italy, the empire was pressed from the north by Serbs and Kievan Rus’, and the Seljuks were waiting on the eastern frontier, making life hard for the empire’s Armenian allies. In 1054, a year that’s much more famous for the “Great Schism” between the eastern (Orthodox) and western (Catholic) halves of the Christian Church, the Byzantines and Seljuks fought a small battle at Manzikert that ended with a Byzantine victory, a Seljuk withdrawal, and a whole lot of ominous foreshadowing. But Zoe had already died by then (in 1050), and Constantine (in 1055) and Theodora (in 1056) followed relatively soon after. They were succeeded by Michael VI (d. 1059), who almost immediately fell out with his military and was forced to abdicate in 1057 in favor of a general named Isaac Komnenos.

Isaac I, who was Byzantine Emperor from 1057 to 1059, was dead set on rebuilding his weakened army, but he inherited an empire that was in economic free fall. Constantine, faced with an empty treasury following an uprising by the Pechenegs (a Turkic people active around the Black Sea) in 1049-1053, debased the popular Byzantine gold coin by about ten percent and generally spent what money he did have on lavish imperial projects rather than on his military. Isaac aimed to change that, but his methods for raising the necessary cash (mostly confiscating land from nobles and the Orthodox Church) made him unpopular. He fell ill, apparently while hunting, and felt compelled to first name the future Constantine X Doukas as his heir apparent and then to abdicate to a monastery (he lingered for a while but died about six months after giving up the throne). Although he, like Isaac, came from a military background, Constantine X generally allowed the palace bureaucracy to control the empire, which meant that the money Isaac had earmarked for strengthening the army was distributed back to influential nobles and the Church.

Meanwhile, in 1064 the Seljuks—now ruled by Sultan Alp Arslan (d. 1072)—seized the Armenian city of Ani in the Caucasus, which had been annexed by Constantine IX many years earlier. This was after the Seljuks had sacked the important eastern Byzantine city of Melitene (modern Malatya) in 1058, so imperial authorities clearly knew something was afoot on their eastern frontier but really couldn’t do anything about it given their political and economic problems. Constantine X died, and his wife Eudokia became regent for their sons. At the behest of the Byzantine military establishment she broke a deathbed promise to Constantine and remarried, to a Byzantine general named Romanos Diogenes, who then became emperor in 1068. But he was not universally well-received.

Let’s stop for a second. If all you’re getting from this narrative so far is that the inner workings of the Byzantine Empire were a mess in the late 11th century and that the Seljuks were emerging as the biggest external threat the empire had faced in quite some time, then you’re getting the point. In the big picture, what’s happening is that the aforementioned Macedonian dynasty, which had ruled since Basil I became emperor in 867, had come to an end with the death of Theodora and the failure of her handpicked successor, Michael VI, to hold on to power. Isaac I was the first ruler of the Komnenid dynasty, but their time in the imperial purple was interrupted (they did return to it later) by the Doukids, starting with Constantine X. Romanos, now Emperor Romanos IV, was technically a Doukid but only by marriage, and once he married Eudokia the rest of the family worked hard behind the scenes to get rid of him, as you’ll see below. Dynastic changeover throughout Roman history could range from so smooth as to be almost imperceptible to extremely chaotic. This period very much fits into the latter category.

This is only the simplified version of imperial events, and even simplified it’s almost impossible to follow all the backbiting and claimants to the throne and wives betraying husbands and unscrupulous dudes marrying their way onto the throne. We can simplify things a bit more and say that the main tug of war within the empire was between a civilian elite and a military elite who disagreed about whether imperial revenues should be devoted to meeting the needs of wealthy denizens of Constantinople or to strengthening the Byzantine military. All this intrigue matters because, as you’ll see, the real problem for the Byzantines after Manzikert wasn’t so much that they lost the battle, it’s that all this court intrigue then exploded into total chaos. It’s the chaos that allowed the Turks to follow up on their victory by pouring into Anatolia and forever changing both its politics and its demographics.

Romanos IV tried, like Isaac I before him, to rebuild the empire’s military strength. Between his own standing army, his personal guard, and lots of mercenaries—and with the help of another currency debasement—Romanos managed to put together an army that Muslim chroniclers, always willing to invent absurd figures in the name of glorifying their victories, numbered between 200,000 and 400,000 soldiers. The actual Byzantine army was probably more like 40,000 to 70,000 soldiers, but whatever its size Romanos took it east to fend off the Seljuk threat. It was during this march east that Alp Arslan first seized Manzikert (now the Turkish town of Malazgirt), which then became one of Romanos’ targets.

At some point Romanos decided to split his army in two, leading one part himself toward Manzikert and sending the other under his trusted general Joseph Tarchaneiotes to Khilat (modern Ahlat) to the south. Dividing a force before battle is usually only done in situations where a commander has definite knowledge of an enemy’s disposition and wants to hit them from two places at once. At the very least you only do it if you know you won’t be losing a numerical advantage. It’s possible that Romanos wanted to fortify Khilat before the Seljuks got there, or he might have been hoping to catch them from two sides. But subsequent events would show that he knew neither where the Seljuks were nor how large their army was. And the danger of splitting your army on a hunch is that if you guess wrong, you’ve just done the first half of “divide and conquer” on your opponent’s behalf.

Something happened Tarchaneiotes’ part of the Byzantine army, because it’s essentially never heard from again. But it’s not clear what that “something” was. Muslim sources record that Alp Arslan met it in battle and wiped it out, but there are no surviving Byzantine sources that mention this and we know that Tarchaniotes himself survived until 1074, which argues against a massacre. The likely explanation is that this army simply fled and/or dissolved, though it’s an open question whether that was due to fear of the Seljuks or because of imperial politics (it could have been a bit of both). Tarchaneiotes may have been aligned with a faction at court that opposed Romanos in the name of Constantine X’s son, Michael VII, who was the “legitimate” heir and was Romanos’ junior co-emperor, so he and his army might have just deserted Romanos, or at least been unwilling to fight for him, for that reason.

Romanos’ column, meanwhile, arrived and took control of Manzikert, at which point Alp Arslan seems to have offered to negotiate a truce. The Fatimids were his main enemy and it seems he wasn’t looking for a major fight with the Byzantines right at this point. For a host of reasons related both to the security of the empire and the political stability of his reign, Romanos felt a negotiated settlement was untenable, so he attacked. He did so even though his army had suffered another significant loss the day before the engagement, when a number of his Turkish mercenaries either deserted or outright defected over to the Seljuks.

The Byzantines appear to have tried to engage the Seljuk army according to standard, age-old Roman tactics for dealing with a nomadic foe. But his army, still in the early stages of his attempted military reform, was too green and too discordant to pull it off. The Seljuks employed a feigned retreat, which is a standard tactic but historically pretty effective when employed by Central Asian mounted archers. The Seljuk force continually gave way in the center and sucked the Byzantine army in, as mounted archers on the ends of the Seljuk line repeatedly struck the Byzantine flanks in hit-and-run attacks. As the day wore on and the Byzantine center was unable to force the Seljuks to engage, while the Seljuks increasingly exploited gaps in the undisciplined Byzantine line to deal heavy casualties. Finally Romanos gave an order to return to camp, but as soon as they started turning around, the retreating Seljuk center also turned and attacked.

The idea at this point would have been for the Byzantine rearguard to punch through an attempted Seljuk envelopment and lead the rest of the army back to camp. But commanding the rearguard was a young nobleman named Andronikus Doukas, a kinsman (nephew) of Constantine X and one of the leaders of the faction that was actually opposed to Romanos being emperor at all. He spread the word among his soldiers that Romanos was dead and, disheartened, they broke formation and ran. Romanos was actually very much not dead, but in the chaos he was captured. Alp Arslan, however, after securing a ransom and the surrender of Manzikert, Antioch, and a couple of other important Byzantine cities, released Romanos and sent him back to Constantinople with an escort. Whether this was intentionally done to sow discord among the Byzantines or not is hard to say, but it worked out brilliantly for the Seljuks either way.

Here’s where the court intrigue comes into play. Even while Romanos was returning to the capital, the Doukas faction was working to have him removed as emperor. Andronikus Doukas’s father, John, who was a very high-ranking Byzantine noble and had the support of the Varangian Guard (the royal bodyguard), forced Eudokia out and became regent for the newly elevated Michael VII. Romanos cobbled together an army of Manzikert survivors and tried to regain his throne, but he was defeated and blinded in 1072, then died in exile of an infection brought on by his blinding.

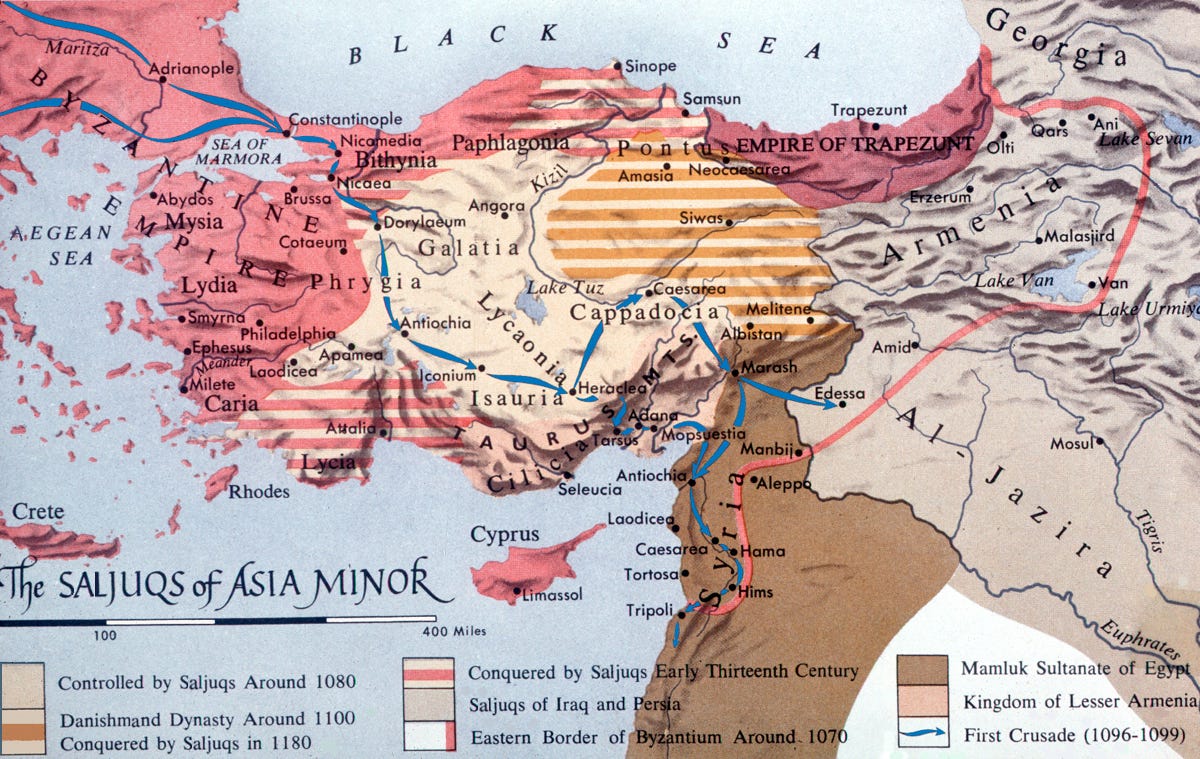

While the Seljuks after Manzikert remained mostly focused on their main enemy, the Fatimids, the battle and the subsequent Byzantine court chaos opened Anatolia up to the Turkic peoples in the Seljuk army. I referred above to the “Seljuk invasion/migration” and that’s because the Seljuks themselves were less a coherent people than a tribal elite ruling over a confederation of peoples. Many of the groups that came with them suddenly found themselves appreciating the grasslands of Anatolia, which happened to be quite suitable to the horse-based steppe nomadic lifestyle that they practiced. So these groups began to move onto the Anatolian plateau and settle, without much in the way of central direction, carving out territories and principalities along the way. I mention this because it’s this disorganization that arguably doomed any Byzantine chance of recovering the lost imperial territory. Had the Seljuks exerted strong central control over their forces one could imagine the Byzantines negotiating a Seljuk withdrawal for, say, Byzantine assistance against the Fatimids. But there was no way to deal systematically with a bunch of independent Turkic bands moseying into Anatolia and taking land piecemeal.

Michael VII repudiated the treaty that Romanos had concluded with Alp Arslan after Manzikert, which proved to have been a huge mistake because the treaty might have (at least temporarily) preserved the heartland of Anatolia for the Byzantines. Repudiating it might have made sense if the Byzantines had the military wherewithal to force a rematch or at least to try to close their Caucasian border, but all the chaos and infighting had sapped much of what was left of the empire’s strength. So much attention was spent on the chaotic mess in Constantinople that the core of the empire was lost. By 1080, most of Anatolia belonged to one Turkic principality or another, and a cadet branch of the Seljuk house was able to carve out an autonomous territory that eventually, with the decline of the Great Seljuk Empire, emerged as the Sultanate of Rum (Rome). The founder of that Seljuk principality, Suleiman ibn Qutalmish, insinuated himself into the fractious politics of Byzantium in such a way that he was able to carve out a sizable territory that included the key city of Nicaea, near Constantinople. The Byzantine Empire was ultimately reduced to its European territories and a strip along the Anatolian coastline.

Manzikert’s effects are hard to completely assess. There’s the school that treats it as the death blow to the Byzantine Empire, which is unsatisfying in that it was another 400 years before the empire completely collapsed (it also seems, at least in some of its older forms, to be based on a mischaracterization of how heavy the Byzantine casualties actually were). And while Manzikert marks a turning point in Byzantine fortunes, ending a roughly two-century period in which the empire mostly got the better of its competition with its Islamic rivals in the east, it’s also clear that there was a lot of rot building up in the imperial center that this battle exposed. Perhaps the impact of Manzikert was not so much about causing the empire to fall, but rather about ensuring that when the empire finally did fall, it would be to a Turkic people. And, lo and behold, the battle did (though it took a while) open the door for a 13th century Turkish bandit named Osman to found what would become the Ottoman Empire. In that sense Manzikert’s greatest repercussion is that it opened Anatolia to Turkic conquest and settlement, and the modern nation of Turkey attests to how thorough that process was.

Manzikert is noteworthy for at least one other reason. Latin Christendom had already begun to take notice of events in the Levant, as the rivalry between the Seljuks and the Fatimid Caliphate had been disruptive to pilgrimage roots from Europe to Jerusalem. The Seljuk victory at Manzikert and the perception that the Byzantines were suddenly in imminent danger only heightened the sense of alarm that was already building in the Latin west. The Byzantines then appealed for help from their fellow (albeit schismatic) Christians, which inspired Pope Urban II to call for nobles and their knights to take up the Cross and head east to save the empire from the Turks and, while they were in the neighborhood, to “liberate” Jerusalem for Christ. The First Crusade followed soon after.