Today in Middle Eastern history: the Siege of Antioch ends, kind of (1098)

The Crusaders go from besiegers to besieged and survive to continue their march on Jerusalem, without Byzantine help.

If you’re interested in history and foreign affairs, Foreign Exchanges is the newsletter for you! Sign up for free today for regular updates on international news and US foreign policy, delivered straight to your email inbox, or subscribe and unlock the full FX experience:

The importance of the Crusades to European history is difficult to overstate. You can drawn links between this movement and the Renaissance, the Reformation, the Age of Exploration, and the collapse of the Byzantine Empire, among other things. But in the short run, at least, it’s fair to say they were a waste of lives and resources. They also showcase some pretty inept military leadership, especially on the European side and even in successful campaigns. Which brings us to the First Crusade’s 1098 capture of Antioch.

During the First Crusade, Islamic principalities in the Levant were in serious disarray politically, and their military capabilities suffered for it. The rise of the Fatimid Caliphate in North Africa and Egypt in the 10th century, followed by its quick expansion into the Levant, had cut what had previously been one semi-unified caliphate into two competing caliphates, both weakened because of their competition. The 9th and 10th centuries also saw the Abbasid caliphs lose power to a succession of “caretakers”—first their own Turkish generals, then the Iranian Buyids in 945, and then the Seljuk Turks in 1055.

As chaos grew at its imperial center, the Abbasid caliphate began slowly decentralizing at its periphery, as regional “governors” began to amass enough strength to act more or less autonomously from the caliph without risk of repercussion (for good measure, they maintained the official pretense that the caliph was still in charge). All of these blows to the unitary authority of the caliph—a competing caliph, a series of imperial usurpers, the progressive loss of control over big chunks of the empire—started to add up.

The Abbasids’ various rivals weren’t in great shape by the end of the 11th century either. The Fatimids struggled to deal with factionalism within their military, as Turkic soldiers faced off against sub-Saharan soldiers and Berbers played each against the other. The Seljuks struggled to adapt what was a loose steppe confederation to the demands of running a centralized empire. Add in the fact that the Fatimids and Seljuks kept fighting each other every chance they got, and were increasingly reliant on foreign mercenaries to do their fighting for them (this will become an issue below), and you’ve got some real issues going on here.

Central authority deteriorated to the point where it seemed like every Muslim governor in Anatolia, the Levant, and northern Iraq controlled his little fiefdom and was either indifferent, or outright hostile, to the governors around him, despite the formal religious and political frameworks that were supposed to drawn them together. These petty kings were as likely to ally with the Christian invaders against other Muslim rulers as they were to band together with other Muslims to try to get rid of the Christians, and it was this discord that the leaders of the First Crusade were able to exploit, usually without even trying, to eventually take Jerusalem.

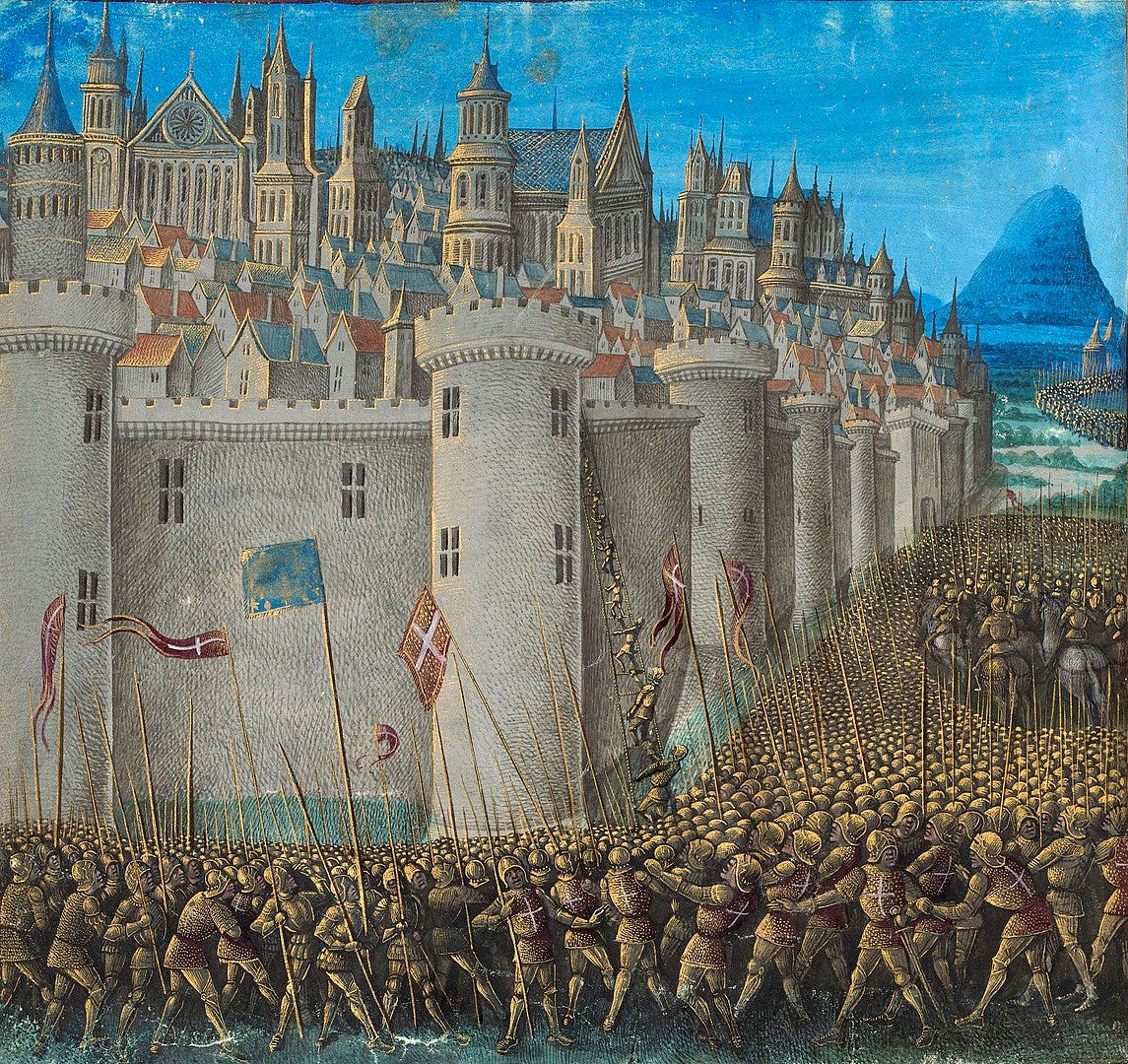

Make no mistake, without that Muslim disunity it’s hard to imagine the First Crusade being any more successful than any of the others, which is to say “not at all,” because the men leading it seem in hindsight to have had no idea what they were doing. I mean, they obviously knew how to fight in the barest sense of the term, but strategy, tactics, everything else was kind of a mystery, and if you thought the Muslims couldn’t get along with one another, imagine cobbling together an army led by a whole cadre of European lords who already hated each other’s guts back home and who simply refused to take orders from one another, no matter who the Pope might appoint as their overall commander. Nothing illustrates the ineptitude-combined-with-dumb-luck nature of the First Crusade as well as the Siege of Antioch, which ended on this day in 1098, when the Crusaders went from besiegers to besieged in what was almost literally the blink of an eye.

Ancient Antioch no longer exists, though its ruins can be found near the Turkish city of Antakya in the southern Mediterranean Hatay province. The Byzantines lost it to the Seljuks in 1085, and its stature as one of the first centers for Christian evangelism made it a prime target of the Crusade, almost as important as Jerusalem itself. In fact, in terms of its commercial importance and location as well as its symbolic value, it was arguably a more important target than Jerusalem, at least for Byzantine Emperor Alexios I Komnenos. When they set out, the Crusaders had promised that any cities and territory taken during the campaign would be “returned” to the Byzantine Empire, and in return Alexios bankrolled and supplied their efforts.

It’s important to remember that the whole crusading movement started with an appeal from Alexios to Rome for fighters to help him drive back the Seljuks and their allies, who were in the process of conquering huge swaths of Anatolia, and restore the Byzantine Empire to its former glory. Jerusalem only became the goal of the campaign when Pope Urban II rebroadcast Alexios’ appeal to the nobility of Western Europe. The idea of “recovering Christ’s city” had more appeal to European nobles than the idea of risking life and limb to protect the Byzantine Empire, which was a rival polity and which, as of the Great Schism of 1054, wasn’t even practicing the same form of Christianity as the Europeans who still looked to Rome for spiritual guidance.

In response to Urban’s call, the Crusade leaders—including Godfrey of Bouillon, Raymond IV of Toulouse, Bohemond of Taranto…Stephen II of Blois…um, Baldwin of Boulogne…uhhh, screw this, there’s like a dozen of these guys—all gathered in and around Constantinople starting in late 1096. All of them were nobles but none were kings, and for that reason you will sometimes see this crusade referred to as the “Princes’ Crusade,” even though none of these guys were princes per se (well, maybe Bohemond but it’s debatable), or the “Barons’ Crusade,” though that term is more often used in connection with a 1239–1241 campaign that is not one of the “numbered” crusades. While in Constantinople, they took some sort of loyalty oath to Alexios. Exactly what kind of oath remains unclear and would become a point of serious disagreement at the end of this very siege, but whatever it was Alexios was satisfied enough to ship the Crusaders off to fight in 1097. By this point one of the emperor’s main considerations was probably just ridding himself of the westerners—he expected his appeal to draw some reinforcements but not an entire army, and anyway the People’s Crusade had exhausted much of his patience.

From very early on, Muslim disunity worked in the Crusaders’ favor. They captured Nicaea, a Seljuk capital, because the ruler there was off campaigning against some other Turkish principality, and then defeated his returning army, which was unprepared for the size of the Crusader force it encountered. Through some fairly underhanded dealing Alexios ensured that the Turks surrendered Nicaea to him rather than to the Crusaders, which exacerbated the enmity that was already starting to build up between the emperor and his alleged saviors.

The Crusaders, accompanied by a Byzantine “guide” named Tatikios, marched through Anatolia relatively uncontested, but also without much by way of supplies because the Byzantines were slow sending new provisions and the Turks undertook a scorched earth campaign after they were defeated. Baldwin of Boulogne, Godfrey of Bouillon’s brother, made a side trip that wound up with him named co-regent of the city of Edessa, which would become the first “Crusader state” in the Near East. And the Crusaders won what could be considered their most iconic victory against a Seljuk army at the Battle of Dorylaeum, which cleared their path to Antioch.

The Crusaders arrived at Antioch in October 1097 and besieged it. Well, they tried, anyway. But their army, big as it was, wasn’t able to fully invest the city, so the Muslim defenders (led by a man named Yaghi-Siyan) were able to bring in supplies to sustain their defense. This was a question partly of numbers, partly of geography—the Crusaders were unable to cross the Orontes River and so they couldn’t cut off Antioch’s access to the Mediterranean. The Crusaders couldn’t take the city by force, mostly because they didn’t have any siege engines, and they also couldn’t starve the defenders into submission, making the end goal of their siege kind of difficult to pinpoint. Worse, the Crusaders set their camps and fortifications up so close to the city walls that the Muslim defenders could pick Crusader warriors off by arrow and even via the occasional sortie out of the city.

The latter miscalculation became particularly troublesome when, after two weeks, the starving Crusader army had picked the surrounding countryside clean of food, and was forced to send out foraging parties. They’d left themselves so vulnerable that Antioch’s defenders and nearby hostile forces were able to pick those foraging parties off one by one. One expedition led by Duqaq, the emir of Damascus, disrupted a foraging expedition that was bringing an entire flock of sheep back to the Crusader camp, and this one setback by itself basically assured that the Crusaders would spend all winter without enough food. Local farmers, many themselves Christian, offered to sell whatever food they could spare to the invaders only at borderline exploitative markups. The soldiers, the ones who didn’t abandon the army and head back home, began eating their horses, who were starving to death anyway, and there are even accounts that some went cannibal, though for propriety’s sake they stuck to eating Turks rather than their fellow Europeans. These reports are sketchy though, in contrast to far more convincing reports of cannibalism later on in the campaign.

All this time, the governor of Aleppo, Ridwan, had been sitting on his hands because he and Yaghi-Siyan didn’t like each other very much. But in February 1098, they patched things up and Ridwan led an army to attack the Crusaders. For some reason, on his way to Antioch Ridwan decided to attack a Crusader detachment on a narrow field that lay between the Orontes River and the Lake of Antioch, which negated his army’s advantage in numbers and consequently led to his defeat. So that rescue attempt was a bust. Then in early March, new supplies finally arrived from Constantinople, and the Crusaders not only had food again but were able to build some siege engines and, at last, to fully invest the city.

Around the same time Ridwan’s army was failing to come to Antioch’s aid, Tatikios, the Crusaders’ Byzantine guide, was breaking camp and heading back to Constantinople. By some accounts, Bohemond had warned him that the other Crusade leaders were planning to murder him. If that’s true then it is probably reasonable to conclude that Bohemond made this story up to run Tatikios off. The reason I emphasize the word “if” is because the actual evidence that Bohemond engineered Tatikios’ departure is sketchy at best and most likely fabricated. The simplest explanation is that Tatikios headed back to try to scrounge up more imperial resources to support the siege, was told that very little would be forthcoming, and then decided not to return to Antioch. His departure marked the effective severing of relations between the Crusaders and the Byzantines.

The siege continued into May, when a new Muslim army marched out of Mosul under its governor, Kerbogha, whose forces were bolstered by those of Duqaq and Ridwan. For reasons passing understanding, Kerbogha decided to spend three weeks unsuccessfully assaulting Edessa instead of going straight to Antioch, buying the Crusaders precious time to prepare. They knew they couldn’t meet Kerbogha’s army in open battle and win, so it was either time to pack up and run or time to force their way into the city so that they could be behind its walls when the Muslims got there.

They decided to go for the city. Bohemond declared to his fellow lords that he was in contact with an Armenian guard in the city named Firoz, who was prepared to open the gates to the Crusaders—for the right price. There’s the problem with relying on mercenaries. Bohemond offered to pay this guy’s asking price provided he got control of Antioch. This of course, violated the deal the Crusaders had made with Alexios. But at this point the Crusader lords had no choice, and their relationship with Constantinople was poisoned beyond repair anyway, so they agreed.

Firoz let the Crusaders into the city on June 2 where they promptly started killing everyone in sight, Muslim and Christian, including Firoz’s own brother. This sounds bad, but in fairness maybe Firoz hated his brother. Who knows? Meanwhile, despite the fact that things had finally broken the Crusaders’ way, soldiers and even a few lords, most prominently Stephen of Blois, kept giving up and heading back to Europe. Stephen stopped in Constantinople on the way home, where he found Alexios actually preparing to get off his behind and lead an army to relieve the Crusaders at Antioch. Stephen told Alexios that the situation was so hopeless that he should just stay home and defend his capital. Alexios was only too happy to take his advice.

Despite all that, the Crusaders now had Antioch, or most of it (a Muslim remnant still held out in the citadel), and had about five minutes to celebrate before they had to immediately turn around and prepare to be besieged, by Kerbogha. And they had effectively no supplies with which to hold out. Kerbogha’s forces arrived on June 5 and besieged the city on June 9. Things looked extra hopeless.

Then, on June 10, a monk traveling with the Crusader army, named Peter Bartholomew, claimed that a vision had told him that The Holy Lance was buried in Antioch’s Cathedral of St. Peter. That’s right, The Holy Lance, the one that had pierced Christ’s side during the crucifixion. This came as quite a shock to anybody who’d seen The Holy Lance in Constantinople or The Holy Lance that was allegedly in the possession of the Holy Roman Emperors, but you can’t quibble over details on a thing like this. Workers began to dig in the Cathedral and found…nothing, until Peter himself jumped into the hole they’d dug and, miraculously, plucked something that could be plausibly called part of a spear right out of the ground (he definitely did not pull it out of his sleeve like I know some of you cynics are thinking). It was a miracle!

The “miracle” of the Holy Lance was reportedly followed a few days later by a meteor falling into the Seljuk camp. Needless to say the Crusaders also took this as another sign that God was truly on their side.

The inspiring Christian version of events has the Crusaders immediately swept up in the ecstasy of the Holy Lance’s discovery, but in reality Kerbogha’s siege went on for another couple of weeks and very nearly starved Antioch’s new defenders into submission. On June 27 they sent Peter the Hermit, the…hero (?) of the “People’s Crusade,” out of the city for a parlay with Kerbogha, most likely to negotiate the city’s surrender in exchange for safe passage. Kerbogha, in the most diplomatic way possible, told him to go piss up a rope, and so there was really nothing left to for the Christians to do but sally forth from the city and try one final, desperate attempt to break the siege.

The Crusaders, possibly emboldened by the “Lance” and definitely on the verge of total collapse, marched out of the city on June 28 with the “Lance” at the front of the army and advanced on Kerbogha’s forces. Muslim archers inflicted substantial casualties on the Crusaders, but when the arrow fire failed to break the Crusader lines and it was time for the real fighting to commence, Duqaq and many of the rest of Kerbogha’s emirs broke and fled. Partly this was due to the relentless onslaught of the Crusader army and partly it was because of that aforementioned Muslim disunity. Most of Kerbogha’s army, when push came to shove, just didn’t have much desire to die for him. For local emirs like Duqaq and Ridwan, the fact is that Kerbogha and his regional ambitions were far more threatening than the Crusaders, and given the choice it was better for them to let these foreigners have the city than see it come under Kerbogha’s control. As soon as the first few units began to flee the army routed, and the now hopeless Muslims remaining in Antioch’s citadel surrendered that same day. The starving Crusaders feasted on the goods left behind in Kerbogha’s camp.

With the city finally under their control, the Crusader lords set about pursuing their real passion: fighting with each other. Raymond of Toulouse, the senior Crusader lord who sort of assumed that everybody was following his lead when in reality they were doing nothing of the sort, was very opposed to turning Antioch over to Bohemond, and actually sent envoys to Alexios to tell him to get to Antioch and claim what was rightfully his. Alexios, no doubt exhausted by the effort it took to almost do something that one time in June, begged off. Here’s where the dispute over what exactly the Crusader lords had promised to Alexios became a major issue. Raymond’s position seems to have been that they promised to turn over anything they conquered to the Byzantines, but Bohemond’s position was that they’d made what amounted to a feudal vassalage relationship. The latter did oblige the Crusaders to obey Alexios but it also obliged him to provide aid and counsel to the Crusaders. As he’d failed to hold up his end of the bargain, Bohemond’s argument went, the Crusaders were free to tell him to get bent.

Eventually the Crusaders asked Pope Urban II to personally take control of the city, but he, probably wisely, refused to get himself caught up in that mess. Raymond and Bohemond continued to squabble for the rest of 1098, until finally the rank and file of the Crusader army, once again at risk of starving since they’d eaten through Kerbogha’s stores and once again picked the surrounding countryside clean of food, threatened to start marching toward Jerusalem without them. At this point Raymond let Bohemond have the city—begrudgingly, one assumes—and Alexios officially got bent.

Peter Bartholomew, the hero of the second siege for finding The Holy Lance, was eventually challenged by his skeptics to undertake an ordeal by fire to prove that he wasn’t lying about the whole thing—his ashes were shipped to his next of kin in Europe. I joke, but in reality we’re told he spent almost two weeks in agony before dying on April 20, 1099, insisting to anyone who still cared to listen that he’d actually been injured in the crush of the crowd after the ordeal and not by the fire itself. His “Holy Lance” may have found its way to Constantinople and to Rome, but at some point in time it may have been conflated with the spear that was already at Constantinople (which definitely wound up in Rome). It seems to have disappeared somewhere along the way. If you’re interested in seeing The Holy Lance today, you can take your pick: there’s one in Rome (a piece of which I think is in Paris), one in the Armenian city of Vagharshapat, and one in Vienna.

In the end it could be argued that, for as chaotic as their siege was, Antioch really created the Crusader movement. It was at Antioch that the expedition definitively became a holy war whose goal was to capture Jerusalem rather than a secular effort to relieve the beleaguered Byzantines. I mean, if this wasn’t a sanctified expedition blessed by The Almighty then how else could they have survived such a dire event? This had far-reaching implications for the Crusaders, of course, but also for the empire.

We don’t know exactly how far Alexios expected the Crusaders to go but it’s likely his main interests lay in two places: Nicaea, because it was so close to Constantinople, and Antioch. For the Byzantines, regaining Antioch would have given them a strong foothold in the east—defensible, easy to supply, and well positioned to control the surrounding region—from which they could have in theory started to rebuild their empire. The Byzantine-Crusader break deprived him what may have been the empire’s last chance to claw back what it had lost to the Seljuks.