Today in Middle Eastern history: the Battle of Siffin (657)

An indecisive engagement prolongs the first civil war in Islamic history.

If you’re interested in history and foreign affairs, Foreign Exchanges is the newsletter for you! Sign up for free today for regular updates on international news and US foreign policy, delivered straight to your email inbox, or subscribe and unlock the full FX experience:

Today is (give or take) the anniversary of the start of the Battle of Siffin, the key battle of the First Fitna (civil war) in Islamic history, about which you can read more here. The caliph, Ali ibn Abi Talib, led an army of 80,000 men (allegedly) against the governor of Syria, Muʿawiyah, and his 120,000 man army (again, allegedly) in what is now the Raqqa province of Syria. Ali’s accession as Caliph had been marred by the assassination of his predecessor, Uthman, and by Ali’s inability and/or unwillingness to bring Uthman’s killers to justice. The latter point became a pretext for resistance among several leading members of the Islamic community who had done quite well for themselves under Uthman. In addition to what I’m sure was their keen sense of justice for the murdered former caliph, they were worried because it looked like Ali was planning to upend the social order in at least three ways:

by replacing Uthman’s regional governors, many/most of whom had been drawn from among the former caliph’s kinsmen

by instituting a more equitable distribution of tax revenues and booty that would put all Muslims, Arab and otherwise, on an equal footing

by moving his capital from Medina to Kufa, thus taking sides in an emerging rivalry between the Syrian and Iraqi portions of the caliphate

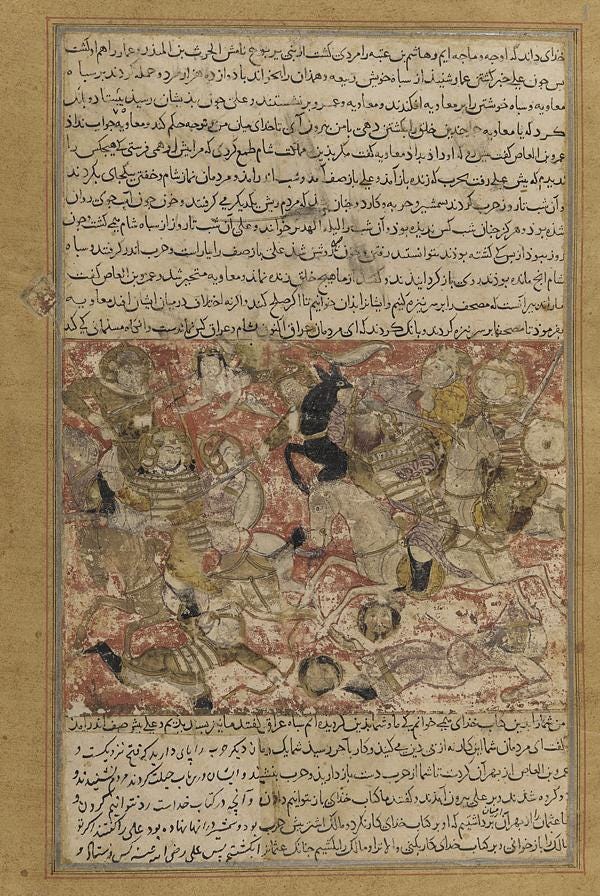

Muʿawiyah refused to acknowledge Ali’s right to replace him as governor of Syria, which meant he was also refusing to acknowledge Ali as rightful caliph, and Ali determined to make him yield. The two armies met at Siffin and camped opposite each other for what we’re told was 100 days, because neither side wanted to fire the first shot, as it were. Then a faction of Ali’s army, known as the Qurra, who had been implicated in Uthman’s murder and were eager for a fight, took it upon themselves to attack Muʿawiyah’s lines.

The armies fought for two days. Despite being outnumbered, Ali’s forces won the battle tactically, dealing (we’re told) Muʿawiyah’s army 45,000 casualties to their own 25,000. This would be a good time to note that all of these numbers, the army sizes and the casualty figures, are too large to be plausible and are almost certainly the result of later chroniclers just picking some numbers that sounded big. Muslim historians didn’t start recording these events until a century or more later, though stories about them would have been orally transmitted prior to that. It’s especially hard to imagine two armies of late antiquity each taking this much punishment in the same battle without either of them falling apart. Yet that’s what the official narrative says happened in this case.

Ali was appalled by the loss of life (which, in the unlikely event those figures above are real, is very understandable) and offered to settle the matter with Muʿawiyah in single combat. But Ali was a legendary fighter whose exploits in “champion-against-champion” battles during the early days of Muhammad’s movement were well known, so Muʿawiyah wanted no parts of that deal. Instead, the Syrian army took the field again on the third day of the battle, but this time carrying copies of the Qurʾan, or pages of it anyway. The reminder that they were killing their fellow Muslims sapped the will to fight right out of Ali’s soldiers. In lieu of continuing the battle, it was decided that Ali and Muʿawiyah would each nominate an arbitrator, and that the two of them would jointly rule on their dispute. Thus, despite the lopsided outcome on the field, Siffin is considered inconclusive, as the battle itself did nothing to resolve the underlying cause of the conflict.

Let’s sum up what happened next, which you can read about in detail elsewhere. The arbitration went just about as badly as possible for Ali. Muʿawiyah’s arbitrator declared that Muʿawiyah should be caliph. Shocking, I know. But Ali’s arbitrator declared that Ali should give up the caliphate in lieu of an election. Ali wound up ignoring the arbitrators’ decision, but he couldn’t renew his offensive against Muʿawiyah because he now found himself at war with the Qurra, who were angry that he’d agreed to the arbitration in the first place. The Qurra split from Ali’s army, and became known as the Khawarij (Kharijites to us non-Arabs), which roughly translated means “the leavers,” because they left Ali’s army. They eventually assassinated Ali as they had Uthman, and Muʿawiyah, who was by this point pretty much the last man standing, became caliph. His accession marks the transition from the Rashidun (“rightly-guided”) caliphs (Abu Bakr, Umar, Uthman, and Ali) to the Umayyad dynasty.