Today in Middle Eastern history: the Siege of Baghdad ends (1258)

A Mongol army destroys one of the largest cities in the world and in every meaningful sense brings an end to the Abbasid Caliphate.

If you’re interested in history and foreign affairs, Foreign Exchanges is the newsletter for you! Sign up for free today for regular updates on international news and US foreign policy, delivered straight to your email inbox, or subscribe and unlock the full FX experience:

The Mongol sack of Baghdad in 1258 brought an end the Abbasid caliphate in most practical senses. It was, obviously, a pivotal moment in world history, and is among the handful of events about which you can genuinely say that the world was one way before it happened and another way after it happened. At the same time, there are ways in which even such a world-changing moment was nevertheless a little anti-climactic.

The thing is, the Abbasids had lost most of their political relevance in 945, when the Iranian Buyids seized Baghdad and put the caliphate under their “protection,” in the organized crime sense of that word. The Seljuks came through in 1055 and “liberated” the caliphs from the control of the Buyids, but rather than actually freeing the caliphate they simply became its new managers. Even before this, the Abbasids had been losing control of their empire—to local dynasties, to the rival Fatimid Caliphate (which took North Africa from them in 909 and then took Egypt in 969), and even to their own Turkish slave soldiers—for decades. Now, it is true that as we approach 1258, the Abbasids had been exploiting the breakup of the Seljuk Empire to reassert some direct authority, at least over Iraq, for more than a century. But for the most part caliphal authority had been reduced to a purely symbolic thing. Caliphs had the ability to confer legitimacy, but no ability to control any territory beyond their literal back yard. So the final collapse of this dynasty wasn’t exactly a bolt from the blue.

That said, though, I think any of us would have a hard time imagining the psychological shock to Muslims around the world to see Islam’s greatest city and its symbolic leader brought down like this. I don’t think we have any modern reference for it—maybe seeing the Nazis march into Paris, though I don’t even think that does it justice. Constantinople’s fall to the Ottomans was probably comparable to some degree, although as weakened as the Abbasids were in 1258, their fall surely didn’t seem as inevitable as the Byzantines’ fall probably seemed in 1453.

It must have been particularly galling that the deed was done not by other Muslims, or even by Christians, who at least were in the same religious ballpark. No, the Mongols were pagans, the kind of people the Quran said needed to be given a choice between conversion and the sword. Granted, there were some Christians and even some Muslims among the Mongol forces by this point, and Buddhism was on the rise among Mongolian elites, but for the most part they were still animists. Whatever their religion, though, the Mongols at their height were arguably the most irresistible conquering force the world has ever seen, and in 1258 they were still near that height.

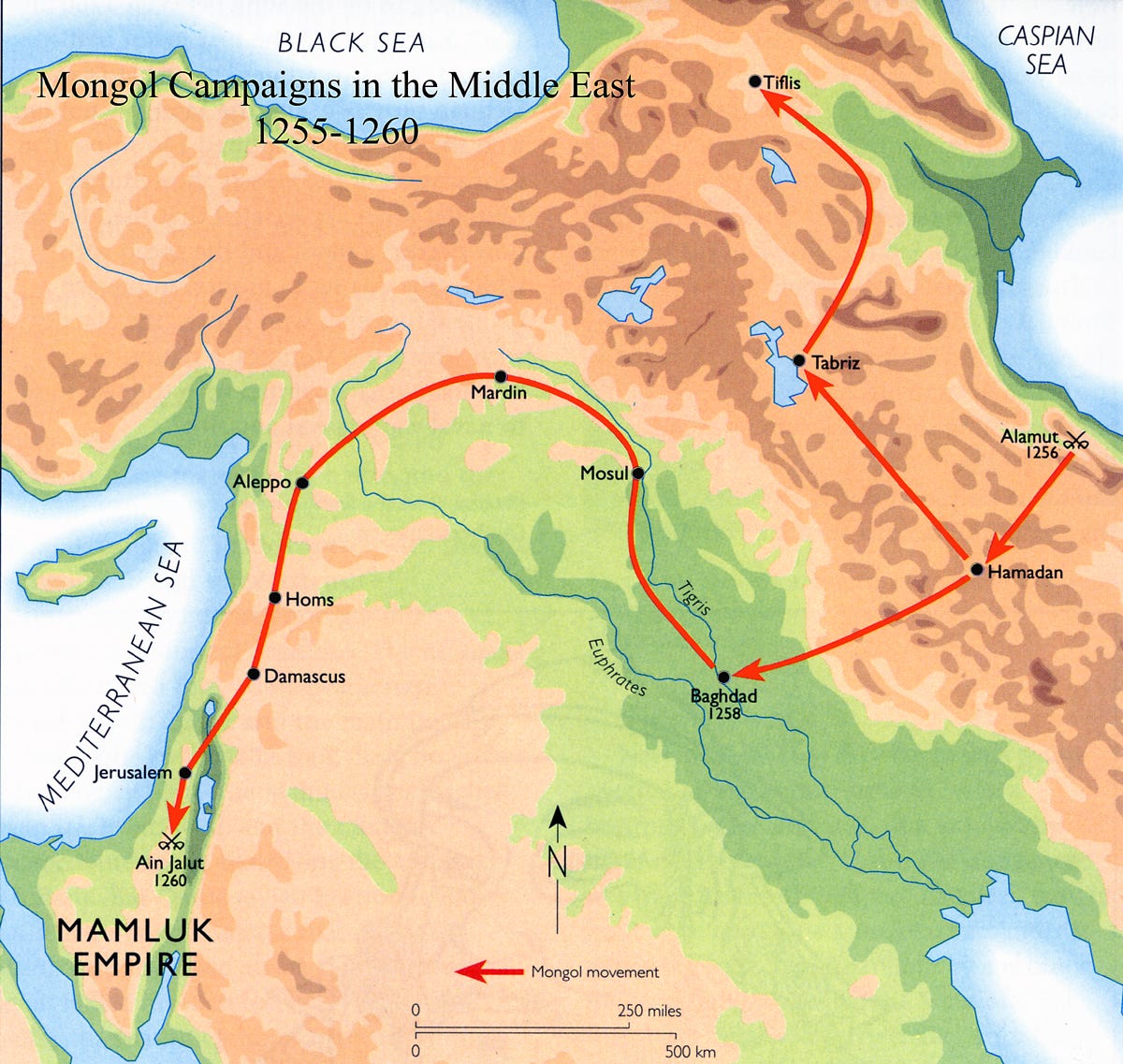

Hoping to avoid what eventually happened, the Abbasids started sending tribute to the Mongols in 1241, after the Mongols destroyed the Khwarazmian Empire that had controlled much of Central Asia and Iran. But the caliphs still saw themselves as the successors to Muhammad, the vicegerents of God on earth—even if that didn't have much practical weight anymore—and so al-Mustaʿsim drew the line at a Mongol demand that he personally report to their court at Karakorum to pay homage to the Great Khan. The Mongols didn’t have a lot of experience at not getting what they demanded. China was always first on Mongolian minds, but in 1257 the Great Khan Möngke (d. 1259) decided to focus on western expansion as well. While assigning one of his brothers, Khubilai (d. 1294), to lead their army in China, under Möngke’s close supervision, he assigned another brother, Hulagu (d. 1265), to take an army west, first to eradicate the troublesome Assassin Order (which had probably made at least one attempt on Möngke’s life) and then to capture Baghdad, unless al-Mustaʿsim finally saw the light on the whole homage thing.

Hulagu forced the surrender of the Assassins’ leader in 1256, which was as close to “eradication” as you could get with such a decentralized organization, and then it was on to Baghdad. He sent messengers to al-Mustaʿsim to see if the caliph had reconsidered on submitting fully to Möngke’s demands. He hadn’t—and yet, inexplicably, it doesn’t appear that al-Mustaʿsim took any steps to fortify Baghdad and/or call up extra defenders from the surrounding area. Why? Beats me. He may well have believed that God would finally put a stop to the Mongols’ conquests rather than allow the “capital city of Islam” to fall to them. Or maybe he was enough of a realist to figure that some extra defenses or a few more troops weren’t really going to make much of a difference.

As the Mongols approached, al-Mustaʿsim sent what soldiers he had out to meet them, to little effect. The siege itself lasted just shy of two weeks, with the caliph belatedly offering to negotiate—an offer the Mongols, who had already seized part of the city’s walls, rejected. It was later written that a delegation of 3000 city notables approached the Mongols to talk and were all executed for their troubles, though it’s possible that account was fabricated or at least exaggerated. Once al-Mustaʿsim had finally surrendered unconditionally, the Mongols set about wrecking what had once been perhaps the most glorious city on earth. They destroyed the “House of Wisdom” and its untold number of manuscripts (more on that in a moment). They tore down and burned buildings that had stood for centuries. They slaughtered tens, possibly hundreds, of thousands of people—men, women, children, everybody.

Why was the destruction so thorough? The Mongols are often portrayed as senseless wreckers, and in general this is an unfair characterization. Don’t get me wrong, they killed a lot of people—by some estimates five percent of the total population of the earth by the time they were done—and wrecked a lot of places. But killing and wanton destruction were not their goals. By and large their real interest was in making money, and to that end they actually preferred to keep cities prosperous and contributing taxes and trade goods. There were exceptions, though. A city that surrendered to the Mongols in exchange for soft treatment that later rebelled would almost certainly be destroyed. And sometimes, especially at the start of a campaign, the Mongols might make an example of a city in order to “convince” subsequent targets that it was a bad idea to try to resist.

In Baghdad’s case, I think there’s some of that latter element, but there may also have been a personal and/or religious motive at play. Al-Mustaʿsim’s replies to Hulagu’s messages were full of warnings about how angry God would be if Hulagu tried to march on Baghdad, and all the divine wrath that was sure to rain down on Hulagu’s head if he transgressed, so the Mongolian prince may have been motivated to make a point about all of that. The Mongols were not above that sort of statement making, and often responded to Muslim and Christian letters about how they were angering God by pointing to their considerable successes and noting that this “God” of which the Christians and Muslims spoke must clearly be on the Mongols’ side. Hulagu was also known to be friendly to Christianity. His mother, wife, and best friend/favorite general were all Nestorian Christians. So that may also have had something to do with it as well. Hulagu did hand the caliphal palace over to the Nestorian Patriarch Makkikha II (d. 1265), if that suggests anything.

There are a couple of stories about what happened to poor al-Mustaʿsim. The most famous is that he was rolled up in a carpet and trampled to death by Mongolian horsemen. The Mongols supposedly believed that it was bad luck to spill the blood of a defeated ruler, so their histories are filled with the creative deaths of conquered chiefs, kings, and emperors. I’m not sure how much credence you can give reports like this, many of which were written long after the fact, relying on “sources” that may not have ever actually existed. There’s another legend that says that when Hulagu saw the caliph’s vast treasury, he locked al-Mustaʿsim inside with no food or water, advising him to eat and drink his gold and jewels. But this one is for sure a fable, a cautionary tale of royal excess where the conquering hero is astonished to find that the decadent kingdom he just conquered was hoarding wealth instead of spending it to benefit the people and strengthen the army. Similar morality tales are told about another foreign conqueror who captured the capital city of a decadent empire in the middle of Iraq—Alexander the Great and his conquest of Babylon.

Baghdad rebounded to some extent as an important city under the Mongols, but it never got anywhere close to the heights it had reached before the Mongols came through. It went back into decline starting in the middle of the 16th century, when it found itself along the often contested frontier between the Ottoman and Safavid empires. It was still an important peripheral city, but the emphasis there should be placed on “peripheral.” Hulagu, meanwhile, kept moving west, until the death of Möngke in 1259 forced him to rush back east to ensure that his rights were respected in the succession process. The shell of an army he left behind tried to extend its conquests into Egypt in 1260, but that didn’t work out so well, and the Mongol world empire finally reached its western (or southwestern, I suppose) limit.

Long-term, the two biggest impacts of the sack of Baghdad were the loss of the caliphate and the destruction of the House of Wisdom, or Bayt al-Hikma. The end of the caliphate—of all caliphates, really, since the Umayyads of Córdoba had been eliminated in 1031, the Fatimids had been put out of their misery in 1171, and no future “caliphate” would achieve broad recognition—was a stunning blow to the Islamic world.

Even as the caliphs had lost their real authority, the idea that there had to be a caliph was still a core part of Islamic political thinking. It was so fundamental that after Baghdad fell Islamic kingdoms used various workarounds to maintain the principle of a caliphate even if there really wasn’t one anymore. Many still struck coins in the caliphs’ names and had them mentioned in Friday sermons, the two most important symbols of sovereignty in the medieval Islamic world, for example. Some rulers continued to claim legitimacy under the authority of al-Mustaʿsim, even though al-Mustaʿsim was very much dead. The Mamluks took in a cousin of al-Mustaʿsim, al-Mustansir, and through him established a new line of Abbasid “shadow” caliphs in Cairo. They’re called “shadow” caliphs by most historians because their supposed “caliphate” was very much a shadow of the real thing. Some local dynasts pledged their allegiance to these Egyptian Abbasids in a pro forma way, but nobody, the Mamluks included, ever seems to have given them much credence. Their claim on the caliphate was eventually “transferred” to the Ottomans in 1517, according to the Ottomans themselves, but by that point it’s hard to say whether anybody cared.

Other regional kingdoms began to experiment with new ways to justify their authority. Many rulers simply claimed it in their own right. Some claimed it on the back of some sort of organizing principle or ideology, like their success in wars against non-Muslim states. The caliph’s seal of approval was briefly replaced by descent from Genghis Khan as a marker of legitimacy, but that eventually fell by the wayside too. Philosophers wrote treatises on the nature of political authority in this brave new world, to explain how these dynasties could be empowered by God without the mediation of the caliph. Over time these independent claims, while perhaps not as intellectually satisfying as the caliph’s imprimatur, came to be acknowledged as legitimate. The Ottomans, especially prior to their conquest of Constantinople, relied on an existential claim to power—we’re in power, so that must be the way God wants it. Again this wasn’t especially edifying if your idea of royal legitimacy depends on endorsements or on passing some sort of ancestral or ideological test, but it was simply an expression of the way the Islamic world worked at that time.

The second great impact of Baghdad’s destruction, the loss of the House of Wisdom, is one of those events like the destruction of the library at Alexandria whose ultimate cost is really unknowable to us today. The House of Wisdom began as Harun al-Rashid’s (d. 809) private library but eventually grew into perhaps the single greatest place of learning in the world between the 9th and 13th centuries. It attracted scholars and students from everywhere, it produced voluminous works in astronomy, math, medicine, and many other disciplines, and its translation office is responsible for preserving works of ancient Greek and Indian scholarship that might otherwise have been lost to humanity. It’s fair to say that the Renaissance would not have happened the way it did (or possibly at all) had European scholars not had access to ancient learning via Arabic translations done at Baghdad and Córdoba, for example. And the Mongols simply destroyed it. Among other atrocities, they dumped the contents of the library into the Tigris River, legendarily turning the water black with ink. Some of the manuscripts were saved by people who simply took them before the Mongols sacked the city, but it’s certain that a lot of works were irreparably lost. As I say, it’s impossible to know the full impact.