Today in Middle Eastern history: the Battle of Ankara (1402)

The young Ottoman Empire is almost crushed before it gets started.

If you’re interested in history and foreign affairs, Foreign Exchanges is the newsletter for you! Sign up for free today for regular updates on international news and US foreign policy, delivered straight to your email inbox, or subscribe and unlock the full FX experience:

The Ottoman Empire was around for an impressive 624 years, from its (murky but generally accepted) beginnings in or around 1299 to its official downfall in 1923. But historians have this irritating urge to periodize everything, which is particularly strong when we’re talking about things that go on for 624 years, and so if you want to study the Ottoman Empire you’ll usually find the material chopped up into chunks.

One very good break point is 1453, for obvious reasons, marking the Ottoman shift from a regional empire to a genuine world power. The death of Sultan Suleyman I, generally considered the last unambiguously successful ruler in Ottoman history (hence one of his epithets, “the Magnificent”) in 1566 is another. The empire underwent a major transition from arbitrary monarchy to bureaucratic state somewhere in the late-18th to mid-19th century, and this is also often used as a transition point though the exact date of the shift is hard to establish. And one often-cited early transition happened in 1402, at the Battle of Ankara, where the Ottoman Empire was almost destroyed before it really got going.

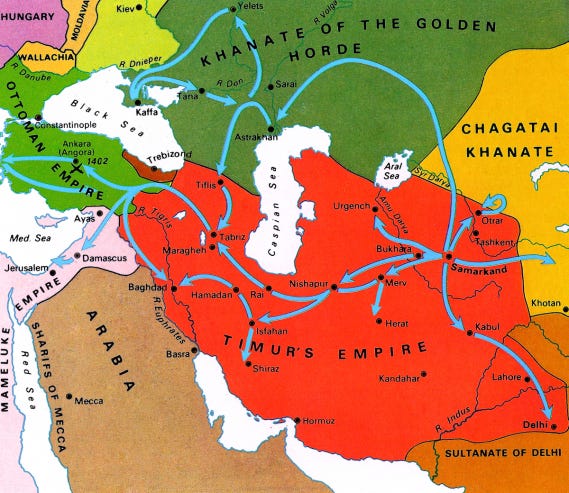

In 1402, most of the region that would later be called the Middle East either belonged or at least owed allegiance to one man, Timur (also known in the West as Tamerlane, a corruption of one of his epithets, Timur-i lang or “Timur the Lame”). Timur was a Central Asian (he’s often called “Turko-Mongol” which basically means that he was ethnically Mongolian but culturally Turkic) conqueror who set out in the late 14th century to rebuild Genghis Khan’s empire and came closer than anybody other than Genghis Khan ever has. Most significantly, after a half-century of virtual chaos across a vast region stretching from Central Asia in the east to the borders of Mamluk Syria in the west, Timur restored some order.

There were downsides, admittedly—chiefly that this order was restored on top of literal piles of human skulls. Well, they may have been literal, or they may have been historical embellishments, we don’t really know for sure. The point is that Timur killed or was responsible for the killing of a whole lot of people—estimates range from 8 to 20 million in his relatively brief (about 35 years, 1370-1405) conquering career. But, hey, omelet, eggs, etc.

Anyway, Timur was undeniably great at what he did, which happened to be conquering places and killing people. Again, he didn’t fully restore the old Mongolian Empire at its height. He never permanently subjugated the Khanate of the Golden Horde (see above), for example, though he invaded it and methodically sacked every single one of its major cities in 1395. Central Asia east of modern Uzbekistan was too pastoral to really be “conquered.” And when he died in 1405 he’d only just begun a campaign to try to bring China into the fold. But he actually surpassed the earlier Mongols in a couple of areas. The Mongols never attempted a serious invasion of India, ostensibly because the climate repelled them, but Timur cut through the Sultanate of Delhi in 1398, looting as much as he could before heading back across the Hindu Kush. Also, the Mongols were totally stymied by the Mamluks in Syria and Egypt, but Timur handled them pretty easily, capturing Damascus in 1400 and subordinating the Mamluks to him for the five years until his death.

The Mongols also never really made much of a splash in Anatolia, preferring to subjugate its rulers, the Seljuks of Rum, as vassals and more or less leave them alone. But around the time of his invasion of Mamluk Syria, Timur encountered a new conquering force in Anatolia, the early Ottoman Empire. Timur’s successful campaigns in the southern Caucasus and in Syria had made tribute-paying vassals of a number of the Turkish principalities that had come to rule bits and pieces of eastern Anatolia after the Seljuk sultanate collapsed in the early 14th century. This was pretty common practice. My reading of Timur’s career leads me to believe that, for all his well-deserved reputation for brutality, he really preferred doing business to making war. Of course, since much of his “business” involved what amounts to an international protection racket, some level of violence was inevitable, but a tidy tribute payment would often dissuade him from pursuing bloodier courses of action.

But to the west, the Ottomans were on the march. Since 1389 they had been ruled by Bayezid I (d. 1403), known as Yıldırım or “the thunderbolt” because of his military prowess. Bayezid succeeded his father, Murad I, after the latter was killed at the 1389 Battle of Kosovo. He consolidated Ottoman gains in Europe before trying something a little different from his predecessors: turning his attention east, into central and eastern Anatolia. Anatolia at this time was divided into cantons, beyliks in Turkish, each ruled by a different dynasty. Some of these were quite powerful, like the Karamanids in southern Anatolia, but many were pretty small and were fairly easy for a militarily powerful sultanate to either conquer or coerce into fealty.

Bayezid ping-ponged between campaigns in Anatolia and campaigns in Europe, but his forces appear to have been large enough to operate in both directions simultaneously, as he defeated Karaman in 1397 while he was simultaneously laying siege to Constantinople. If the Ottomans had taken Constantinople at this time, when their European enemies had been exhausted either at Kosovo or at the 1396 Battle of Nicopolis, it’s entirely possible that they would have had a clear path right into central Europe. But Bayezid made the mistake of drawing Timur’s attention by demanding his own protection money from some of those principalities that were already paying Timur. The response was, you might say, decisive.

As usual, the size of the armies that met at Ankara can’t be reliably gleaned from the historical sources, some of which give Timur anywhere from 600,000 to over a million men, which would have been logistically impossible. Timur clearly seems to have had more men than Bayezid, and a reasonable estimate would probably put his army at somewhere around 150,000 against something less than 100,000 (90,000 or so) for the Ottomans, most of them hurriedly marched east from among the forces besieging Constantinople and others that had been sent to campaign in Hungary. This was a problem for Bayezid, but the bigger problem for Bayezid was that many of his men were there only because they had to be, because they were from one or another of those Anatolian cantons that Bayezid had been subjugating as he expanded east. Given the choice between paying tribute to Timur, who’d been a relatively hands off boss as far as his Anatolian vassals were concerned, and being absorbed into the encroaching Ottoman Empire, many Anatolian fighters preferred Timur.

When the fighting started, then, it didn’t take much for quite a few of those fighters to abandon Bayezid and surrender to Timur or even, in a few cases, to switch sides completely and fight for him against the Ottomans. Ironically, among Bayezid’s best fighters were his relatively new Serbian vassals, who’d been forced to accept Ottoman control after Kosovo. They seem to have done a great deal of damage to Timur’s forces. But ultimately Timur’s advantage in men and his crafty decision to divert a nearby stream in order to deprive the Ottomans of access to water was enough to carry the day. Most damaging from the Ottoman perspective, as we’ll see below, was the loss of Bayezid, who was captured and spent the rest of his life (such as it was; he died in March 1403) as Timur’s prisoner.

Timur, as I’ve already mentioned, died in 1405, and his empire was ruled ably (though its days of expansion were over) by his son Shahrukh (d. 1447) for over 40 years. It began to fall apart after Shahrukh’s death, however, and was altogether gone by 1507, when the Uzbeks conquered Herat. But a descendant of Timur, Babur (d. 1530), tired of trying and failing to win back his birthright from the Uzbeks, conquered northern India and established the Mughal Empire in the 1520s.

As for the Ottomans, Ankara shattered the early empire and almost scattered its remnants to the winds. The Ottomans lost all of their gains in Anatolia and had many of their gains in Europe rolled back (the Serbs became independent again, for example, and the Byzantines got a reprieve). But Timur didn’t entirely do away with the Ottoman dynasty. Instead, he set one of Bayezid’s sons, Mehmed I, in charge of the drastically diminished Ottoman principality and, more or less, told him to go and sin no more. But Bayezid had a few other sons (Isa, Musa, Suleyman, and Mustafa), and they all seem to have had their own ideas about the succession. The Ottomans spent the next 11 years embroiled in a civil war, known as the Ottoman Interregnum, before Mehmed merged as the undisputed sultan in 1413. Their encounter with Timur proved to be a setback, but not a permanent one.