Today in Middle Eastern History: the Battle of Ayn Jalut (1260)

The seemingly unstoppable Mongolian conquest is stopped, permanently, in western Asia.

If you’re interested in history and foreign affairs, Foreign Exchanges is the newsletter for you! Sign up for free today for regular updates on international news and US foreign policy, delivered straight to your email inbox, or subscribe and unlock the full FX experience:

In 1260, the Mongols were near the height of their power and reach, particularly in the Middle East. In less than 10 years, Mongol armies had stormed through Iran and Iraq, crushing the notorious “Assassins” sect and ending the Abbasid Caliphate in the process. They’d even invaded northern India several times but for multiple reasons—including that the Mongols found the Indian climate completely disagreeable—they never made much headway there. With the empire simultaneously expanding into eastern Europe and southern China, it must have seemed like the Mongols would go on expanding until they ruled the entire world.

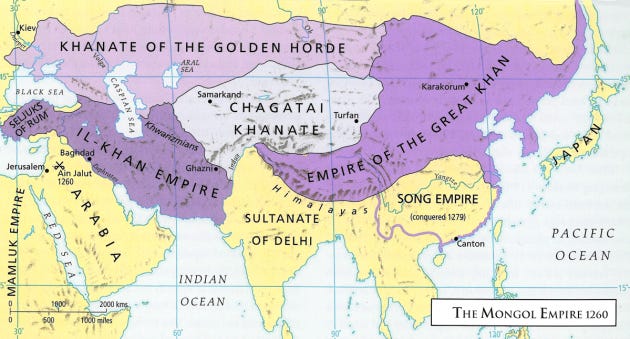

The architect of this latest round of expansion was the Great Khan Möngke, who had come to power in 1251, after something of an internal coup d’etat forced the descendants of Genghis Khan’s third-eldest son, Ögedei, out of the Great Khanate and installed the descendants of Genghis’s youngest son, Tolui, in their place. It’s really at that point that the Mongol domains stopped being one very large empire and started devolving into four smaller-but-still-really-big empires:

The Jochid Khanate, often called the “Khanate of the Golden Horde” though the Mongols themselves don’t seem to have used that name. This realm was located on the Eurasian steppe (Russia, Kazakhstan, eastern Europe) and was ruled by descendants of Genghis Khan’s oldest son, Jochi. The circumstances of Jochi’s birth make it possible, or even likely, that he was not Genghis Khan’s biological son, but the conqueror claimed him anyway.

The Chaghatai Khanate was located in Central Asia and was ruled by descendants of Genghis Khan’s second-oldest son, Chaghatai.

The Ilkhanate, or the Khanate of Hulagu (we’ll get to him in a moment), was located in the modern Middle East and was ruled by descendants of Tolui. The title “Ilkhan” means something like “subordinate khan” and reflects the ruler’s status relative to the Great Khan in the east.

Speaking of which, the final khanate was the Empire of the Great Khan in China (where it was known as the Yuan Dynasty), Mongolia, and Korea. This was also ruled by descendants of Tolui.

The Great Khan, who first ruled from Mongolia but later from the Chinese city of Khanbaliq (modern Beijing), was the nominal overlord of the rulers of these other empires, but in practice all four were separate entities and frequently went to war with one another—though by 1260 things hadn’t fallen apart that completely yet.

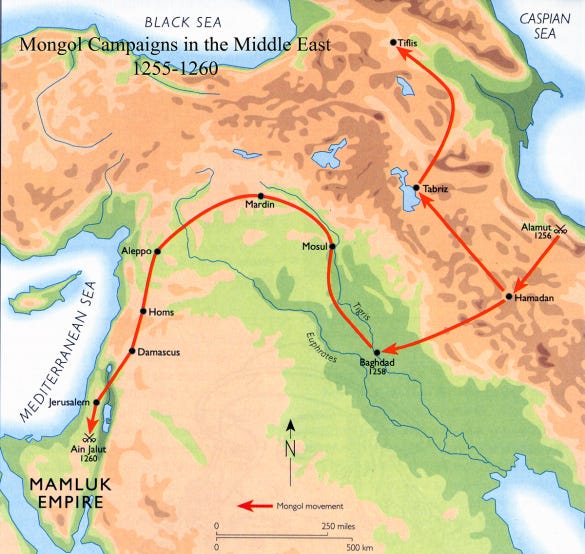

Upon his succession, Möngke had one thing on his mind: expansion. He put one of his brothers, Hulagu, in charge of an expedition to the Middle East and put another, Kubilai, in charge of a new China campaign. As we noted above, Hulagu’s army swept through the region, eliminating the Assassins (who’d made the mistake of trying to murder Möngke and were therefore the main target of the campaign) in 1256 and then capturing Baghdad, where he executed the last widely-accepted Abbasid Caliph, in 1258. By September 1260 his armies were in Syria, having taken Aleppo and Damascus, and were poised to push south into Egypt. Hulagu sent envoys to Cairo demanding Egypt’s surrender, but the envoys’ heads were later seen decorating Cairo’s city walls. So that would be a “no” then.

Two things conspired to ultimately stop the seemingly unstoppable Mongolian advance. First, Egypt’s desperately weak Ayyubid ruling dynasty was overthrown by its slave soldiers, the Mamluks, in 1250. Overnight, Ayyubid weakness was replaced by Mamluk strength. What’s particularly relevant here is that the Mamluks, most of whom had been purchased as slaves from the central Eurasian steppe, were accustomed to the same Central Asian style of warfare as the Mongols. While Mongolian horse archery and battle tactics (like the infamous “feigned retreat” that Genghis Khan used so effectively) were unfamiliar and confusing to many armies the Mongols encountered, the Mamluks knew them quite well. The Mamluks also benefited from very capable leadership, between their sultan, Qutuz, and his chief general, Baybars, who commanded their vanguard.

The second complication for Hulagu’s forces was the eccentricity of Mongolian politics and the death of Möngke in August 1259. Mongolian custom meant that upon the death of a ruler, a tribal kurultai (council) had to be called, where all the leading princes would gather to select a new Great Khan. Once Hulagu learned of his brother’s death (news traveled slowly in 13th century Asia), he had no choice but to attend. As Möngke’s brother, he was a candidate to become the new Great Khan (it would almost certainly be either him, Kubilai, or their brother Ariq Böke), and at the very least he wanted to be there to defend his own interests. And of course, no prince could just show up to a kurultai alone—you had to bring your army with you to be taken seriously. So Hulagu left a small residual force with his senior general, Kitbuqa, and took the rest of his army back east to stake his claim. When Qutuz found out about this, he knew it was time to attack. He assembled an army and marched it north into Palestine, and Kitbuqa obligingly marched his army south to meet it.

There were still Crusader kingdoms in the region at this time, and one, Antioch, became a Mongolian vassal and participated in Hulagu’s conquests of Aleppo and Damascus. The Mongols made diplomatic overtures to the Crusaders at Acre, but as Mongolian diplomatic overtures generally took the form of Mafia-style protection rackets, the Crusaders didn’t take them up on their offer. The Mamluks also approached Acre about an alliance, and while the Christians were more amenable to a deal with the Mamluks, they decided to remain technically neutral. In reality this was more of “neutral, but” policy, as they allowed the Mamluks to pass unmolested through Acre’s territory on their way to meet the Mongols.

Ayn Jalut means “the Spring of Goliath” in Arabic, and when the two armies faced off there (in the Jezreel Valley, in the Lower Galilee region of modern Israel), you could have made an argument that either one was the David to the other’s Goliath. The Mongols were the Mongols—they’d conquered much of the world by that point, and surely anybody who stood against them was the underdog…right? On the other hand, this was a tiny Mongolian army (10,000-20,000 fighters by most estimates) facing what is generally believed to have been a substantially larger Mamluk force that knew the terrain. The Mamluks also had religious zeal on their side. Where the Mongols were a hodgepodge of animists, Buddhists, some Muslims, Nestorian Christians, and more, the Mamluks were all Sunni Muslims who, in the wake of the Mongol sack of Baghdad, now believed themselves the “Defenders of Islam.” The Mamluks also appear to have been using some kind of very early firearms, though their impact was likely limited to scaring Mongolian horses as opposed to efficiently killing Mongolian fighters.

Whatever combination of numeric superiority, technological superiority, ideological devotion, etc., was responsible for the outcome, the upshot of Ayn Jalut is that the Mamluks won. They did it by, of all things, confusing the Mongols with tactics that the Mongols themselves used all the time, in particular a feigned retreat by Baybars and his vanguard that suckered Kitbuqa and his army into a trap. Even at that, the Mongols put up such a fight that Qutuz had to personally lead his reserves into the battle, shouting Islamic slogans all the while, to ensure victory. The Mamluks suffered heavy losses, but the Mongolian army was almost completely annihilated, including Kitbuqa himself. Egypt was preserved from the Mongol conquests, and eventually Syria (which proved impossible for the Mongols to hold) and the rest of the Levant were absorbed into the Mamluk sultanate as well.

Qutuz is still revered today as the man who defended Islam’s last bastion against the surging Mongols, but he didn’t live long enough to bask in his glory. He was assassinated on the way back to Egypt, probably by Baybars. The general was expecting Qutuz to promote him to some lofty position like governor of Aleppo or the like, as a reward for his performance in the battle, but Qutuz had Baybars pegged as an ambitious threat and refused to feed that ambition. Whether Baybars was directly involved in the assassination or not, he’s the one who benefited by becoming the new sultan. As such, he immediately went after the Crusaders, ostensibly because Antioch had aided the Mongols but really out of a desire to finally rid the region of their presence. He captured a number of Crusader cities, including Antioch and Jaffa in 1268, and Ascalon (which he destroyed) in 1270, and these losses put the Crusader states into a death spiral that ended with the Mamluk capture of Acre, the last Crusader state left standing, in 1291 (several years after Baybars’ death in 1277).

Hulagu backed his brother Kubilai’s appointment as Great Khan against the rival claim of Ariq Böke, then returned west as those two prepared to fight a civil war that would last until 1264 and would really spell the final end of Mongolian unity. He was itching for another crack at the Mamluks, but instead he got sucked into a war with his cousin Berke, the ruler of the Golden Horde. Berke had converted to Islam sometime in the 1240s, and watched in horror when Hulagu sacked Baghdad and executed the caliph. He also believed that Hulagu had taken territory in the southern Caucasus that really belonged to him, and he supported Ariq Böke in the civil war back east. So Berke signed a treaty with the Mamluks, and then went to war with his fellow Mongols. Hulagu suffered a significant defeat to the Golden Horde in the northern Caucasus in 1263, really the only serious fighting of the war, and then died in 1265 (Berke died the following year).

The Battle of Ayn Jalut is an event of considerable importance in world history, a genuine turning point. It stopped the Mongols’ westward expansion and kept Egypt and Syria under Muslim control at a time when the religion of Islam itself seemed to be teetering on the brink. Although the Ilkhanids—the dynasty founded by Hulagu—would eventually convert to Islam, in 1260 there was no reason to believe that this would happen, and in fact it probably wouldn’t have happened without Ayn Jalut. Had Hulagu delayed his trip east and the Mongols had defeated the Mamluks—a strong possibility, considering the damage they inflicted on the Mamluks even while greatly outnumbered—the history of Egypt, the Middle East, and indeed Islam as a world religion could have been very, very different.