Today in Middle Eastern history: Operation Exporter begins (1941)

British and Vichy French forces clash in Syria in one of World War II's most forgotten campaigns.

If you’re interested in history and foreign affairs, Foreign Exchanges is the newsletter for you! Sign up for free today for regular updates on international news and US foreign policy, delivered straight to your email inbox, or subscribe and unlock the full FX experience:

The Middle Eastern front in World War II often merits only a brief mention before you move on to Pearl Harbor, the Pacific campaign, and so forth. So Operation Exporter, or the Syria-Lebanon Campaign, doesn’t get that much attention. Indeed, even during the war news about the campaign was downplayed or outright suppressed in Britain, for a very simple reason: it involved Britain fighting France. Yes, we’re talking about a Vichy French army, but it hadn’t even been a year since the last British and Free French troops fled France, and British authorities felt that morale would suffer if people found out that they were now at war with what was left of the French army.

For our purposes none of that matters. And in fact it’s a shame we don’t hear more about Operation Exporter. The fall of France to the Nazis, and the campaign that ensued, played a not-inconsiderable role in liberating both Syria and Lebanon from French colonial rule. So we should definitely check it out.

As soon as France fell to the Nazis, a Middle Eastern conflict with Britain became inevitable. The Vichy government agreed to give German and Italian forces access to France’s Middle Eastern air bases, and London feared its railways were next. Control of Syria could have allowed the Axis to open up a second front around Egypt (creating a pincer effect with Erwin Rommel’s Afrika Korps that was advancing on Egypt from the west). Perhaps more worrisome was Syria’s potential use as a highway for Axis-provided supplies to reach the pro-Axis (to be fair, it was more “anti-British” than “pro-Axis”) Iraqi government of Rashid Ali al-Gaylani. Britain addressed that threat when it invaded Iraq and removed Gaylani from power in late May. But Gaylani managed to flee to neighboring Iran (which was at this point ruled by the “neutral” but Axis-sympathetic Reza Shah), and so there was still a concern that, with Axis support, he could try to make a comeback. The British loss of Iraq would have left India vulnerable, which meant the threat was a critical issue for London.

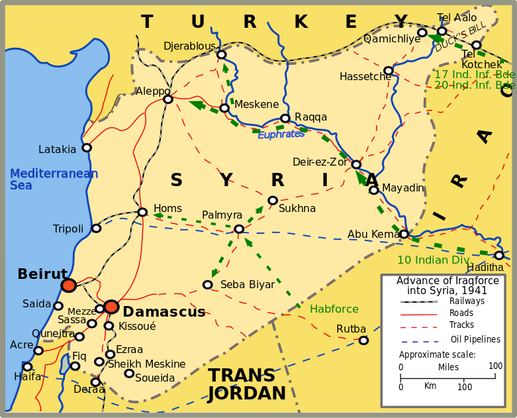

The Vichy forces in Syria greatly outnumbered Britain’s Middle Eastern forces in men and aircraft, particularly after they transferred a couple of hundred aircraft from France and French North Africa, but a couple of things worked in the Allies’ (the Free French army participated as well) favor. For one thing, Britain controlled enough of the Middle East to attack Syria from Palestine in the south and from Iraq in the east simultaneously, and the Allies made the most of this by dividing their forces into four columns that would each strike at different spots. Two units advanced north from Palestine to take Beirut and Damascus, while two more attacked from Iraq, one heading toward Palmyra and the other to Aleppo via Raqqa. The air war also went very well for the Allies, in that the vastly outnumbered British air force was able to destroy much of the French air force on the ground, where its numbers advantage didn’t matter. Finally, for whatever reason, Germany never sent any substantial assistance to Syria, possibly due to disagreements with Vichy French commander Henri Dentz, who declined even the marginal aid the Germans did offer.

The four Allied columns began their simultaneous attacks on June 8, 1941. A series of battles followed over the next month. Of the Allies’ four targets, Damascus fell on June 21, Palmyra on July 1, and Beirut on July 12, and at that point Dentz surrendered. The fourth column never made it to Aleppo because the campaign ended, but it did capture Deir Ezzor on July 3 and Raqqa on July 5. The combatants signed the Armistice of Saint Jean d’Acre on July 14. Its terms called for Syria and Lebanon to be turned over to Free French control, albeit under British military oversight. Of the nearly 38,000 French POWs in Allied custody after the armistice was signed, around 5700 opted to defect and join the Free French army, while the rest were repatriated back to continental France.

With the Vichy government out of the picture, it fell to Charles de Gaulle’s Free French government in-exile and Britain to determine the future for Syria and Lebanon. Yes, I realize there was a decided lack of Lebanese and Syrian input into that discussion, but that’s just how things went in the colonial Middle East. And as it turned out, the final outcome was probably what most Syrians would have wanted. After World War I, many Arabs living in what would become Syria (and Lebanon) were strongly resistant to the idea of becoming a French mandate. Many Syrian grandees offered to place themselves under British, or even American, control instead. A brief movement to institute a Syrian monarchy under the Hashemite Prince Faysal (later King Faysal of Iraq) was snuffed out by French forces. Many Syrians preferred almost anything to what what they actually got, which was French colonial rule.

Now they finally got independence. Britain and de Gaulle had concluded in a general sense, prior to the invasion, that both Syria and Lebanon should be granted independence upon the successful conclusion of the campaign. De Gaulle, to his credit, managed to adhere to the terms of this arrangement right up until he had to actually fulfill it, at which point he reinstated the mandates. Unfortunately for his plans of a restored French Levantine empire, Britain was most vocal on the subject of Syrian and Lebanese independence, and suffice to say that in 1941 the tattered remnants of pre-war France were in no position to pick a serious argument with the British government. De Gaulle did another about face—he was for Syrian independence before he was against it, you might say, and then he was for it again—and announced that elections would be held in both countries in 1943.

Lebanon dates its independence to those November 1943 elections, but Syria dates its independence either to the official end of the French mandate, in October 1945, or to the withdrawal of the last French soldiers from Syrian territory, in April 1946 (April 17 is a Syrian national holiday known as “Evacuation Day”). However you slice it, both countries gained their independence as a result, at least in part, of Operation Exporter.