Today in Middle Eastern history: Khomeini returns from exile (1979)

Iran's most famous opposition figure returns home just in time to seize control of the country's revolution.

If you’re interested in history and foreign affairs, Foreign Exchanges is the newsletter for you! Sign up for free today for regular updates on international news and US foreign policy, delivered straight to your email inbox, or subscribe and unlock the full FX experience:

One of the ironies of the modern Middle East is that Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini became the most popular person in Iran during a time when he wasn’t living there. After a career spent mostly as a non-political religious scholar (albeit one who was known within academic circles to be skeptical about anything that smacked of “Westernization”), Khomeini emerged suddenly into the public consciousness in the the 1960s as perhaps the most vocal domestic critic of Mohammad Reza Shah Pahlavi. But he reputation really grew only once he’d been exiled for that criticism.

The thing that drove Khomeini to make his very public debut as a political figure was the Shah’s “White Revolution,” a package of land and political reforms that were supposed to raise the quality of life for poor farmers and factory workers and to improve education and health care for all Iranians. Prior to the White Revolution, Khomeini had largely followed the quietist example of his teachers, but now he railed against the reforms for stripping religion out of education and for instituting Westernizing changes like giving women the right to vote. In doing so he attacked the Shah directly, personally, which the clergy—though unhappy with the Shah in many ways—had tended not to do previously.

Openly political clergy have been a problem for secular-authoritarian Iranian rulers for centuries, a fact that was undoubtedly well-known to the Shah, and so it didn’t take long for him to move against Khomeini. On June 3, 1963, which was Ashura that year, Khomeini gave a speech in which he compared the Shah to Yazid, the Umayyad caliph who was responsible for the martyrdom of Husayn at Karbala (so, uh, he’s not well-regarded among Shiʿa), and calling him a “wretched, miserable man.” The Shah had Khomeini arrested two days later. Somewhat unexpectedly, given that Khomeini’s public profile before this had been virtually zilch, his arrest sparked massive riots, known as the Movement of 15 Khordad, in which hundreds of protesters were killed. Khomeini was eventually released in August.

Having learned his lesson, Khomeini never spoke out against the Shah again. Just kidding! He kept up a relentless public criticism and finally, in October 1964, earned himself another arrest. This time, the Shah had Khomeini exiled. At first he went to Turkey, but by late 1965 he’d established himself in the important Shiʿa city of Najaf, Iraq. There he became a marjaʿ, or a marjaʿ-i taqlid, a title that in Shiʿa Islam refers to a religious figure who serves as a model for believers to emulate (it’s the highest rank in the Shiʿa religious hierarchy). Iranians started to claim that Khomeini had been prophesied by the 12 imams and that you could see his face in the full moon. It got a little weird, in other words. Khomeini stayed in Najaf until 1978, lecturing on the appropriate form of Islamic governance and refining his theory of the vilayat-i faqih, a modern interpretation of a long-standing Shiʿa principle that Khomeini framed as government by the learned Islamic jurist.

You don’t have to read too far between the lines to get that Khomeini was talking about how he should be governing Iran and not the Shah, but the theories he developed were a direct challenge to every secular government in the Islamic world. And so in 1978, Iraq’s go-getter of a vice president, Saddam Hussein, had him tossed out of Najaf (no doubt with the Shah’s blessing) and he sojourned on to France. Meanwhile, the White Revolution—which was initially fairly popular with the Iranian public—was failing to do many of the things the Shah promised it would do. Specifically, the land reform that lay at the core of the Shah’s reforms seems merely to have replaced large hereditary Iranian landowners with large commercial Iranian agribusinesses, with little benefit for the Iranian peasantry. And so Khomeini’s early criticisms began to seem prescient.

If everybody was hoping that Khomeini would live the traditional exiled academic’s life on the French Riviera or whatever, those hopes were quickly dashed when the revolution really heated up and Khomeini began essentially directing its course from France. The Shah was dumped out of power (and out of Iran) by the Iranian people on January 16, 1979. In one of his final acts to try to hang on to power, before things became totally untenable and he got the hell out of Dodge, the Shah named Shapour Bakhtiar, a political scientist and preeminent member of the secular opposition, as Iran’s new prime minister, with the understanding that Bakhtiar would govern the country as a secular republic with minimal royal input. The Shah’s subsequent departure and Khomeini’s return from exile wrecked Bakhtiar’s deal. In a hilarious footnote to his overthrow, before he left the country the Shah appointed a council to perform royal duties in his absence. The appointed chair of that council promptly flew to France and tendered his resignation to Khomeini.

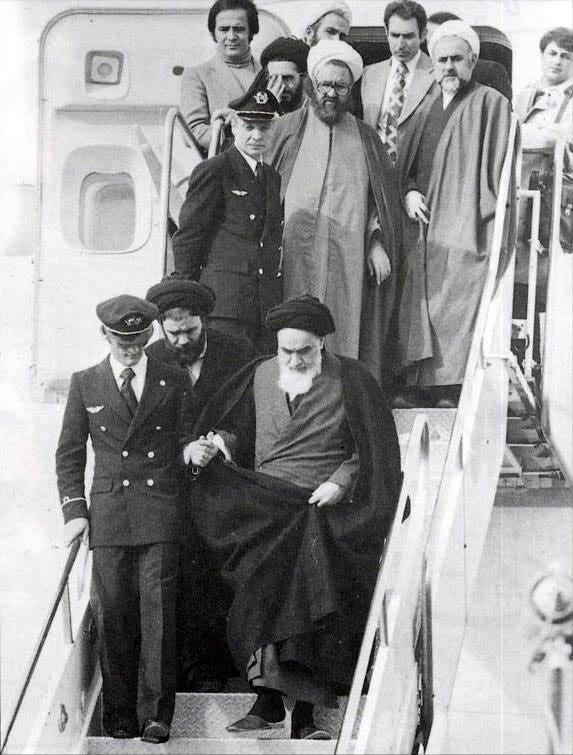

Millions of people welcomed Khomeini back into the country, meeting his plane at the airport and following a procession that he led to Behesht-i Zahra, the largest cemetery in Tehran and the burial place of many who had been killed by the Shah’s government. There Khomeini gave a fiery speech in which he slammed Bakhtiar’s government:

“These people are trying to bring back the regime of the late Shah or another regime. I will strike with my fists at the mouths of this government. From now on it is I who will name the government,” he claimed.

The BBC is being polite there in its translation—I haven’t seen the Persian text of Khomeini’s speech, but I’ve seen it translated in other places as something closer to “I’ll kick their teeth in.” In fairness, Bakhtiar’s government was broadly unpopular, so it wasn’t just Khomeini itching to get rid of him. Ironically, even though Bakhtiar had been a long-time opponent of the Pahlavi ruler, the fact that the Shah had appointed him prime minister—even though it was meant as a final capitulation to the revolution—tied Bakhtiar inexorably to the hated monarch in the eyes of the Iranian public.

Bakhtiar dismissed Khomeini’s statement, saying “Don’t worry about this kind of speech. That is Khomeini. He is free to speak but he is not free to act.” Give him points for putting on a brave face, at least. He was forced to step down about two weeks later in favor of Khomeini’s preferred choice as prime minister, Mehdi Bazargan (who had actually been Bakhtiar’s political ally in the opposition). Bazargan, it should be noted, quit in November 1979 in protest over the seizure of the US embassy and over the revolution’s increasingly authoritarian direction. Bakhtiar finally fled Iran in April, going into his own exile in France. There he established the National Movement of Iranian Resistance and survived several Iranian assassination attempts before they finally got him in 1991. Khomeini, of course, ruled Iran as Supreme Leader, per the Islamic constitution that was adopted in November 1979, until his death in June 1989.