Today in Middle Eastern history: the Church of the Holy Sepulchre is destroyed (1009)

An erratic Egyptian ruler briefly purges his empire of Christian holy sites, causing panic among European Christians.

If you’re interested in history and foreign affairs, Foreign Exchanges is the newsletter for you! Sign up for free today for regular updates on international news and US foreign policy, delivered straight to your email inbox, or subscribe and unlock the full FX experience:

It would be easy to read the title of this post and think, “See? Muslims persecuting Christians; it’s been going on for over a thousand years!” But that would be unfortunate, because it wasn’t “Muslims” who ordered the destruction of the church that (allegedly) stands on the site of Jesus’s crucifixion and burial. It was, as the title says, the Fatimid Caliph al-Hakim, whose overall behavior has led some historians to conclude he may have been mentally ill. Obviously that’s speculative, because 11th century mental health diagnosis just wasn’t all that great. Plus, we’re biased by the sources, many of which were written well after al-Hakim reigned (996-1021) and by people who were inclined for political and religious reasons to regard him unfavorably. There are, to be fair, other historical traditions that identify al-Hakim as an ideal ruler and even a divine or quasi-divine figure. But what we know of him, most especially the decisions that led to today’s story, suggests a guy who was at the very least prone to some incredible mood swings.

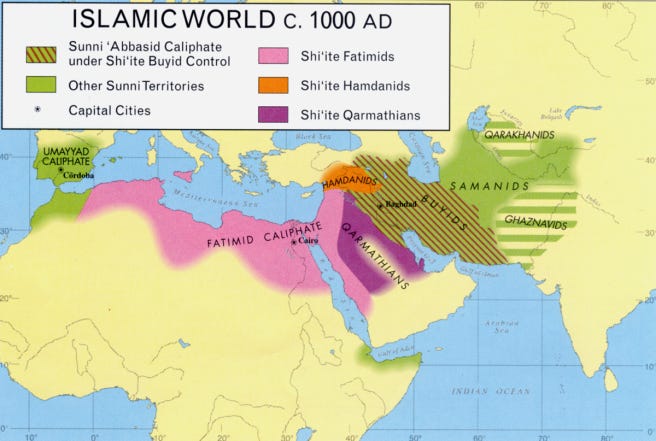

First, a little background if you’re not familiar with the Fatimid Caliphate. The Fatimids were a dynasty of Shiʿa rulers belonging to the Ismaʿili branch of Shiʿism, as opposed to the Imami or “Twelver” branch that is most prevalent today, especially in Iran. Those two groups diverged after the death of Jaʿfar al-Sadiq, their last mutually recognized imam, in 765. Ismaʿilis say that Jaʿfar designated his eldest son (whose name was, you guessed it, Ismaʿil) as his successor. Which he very well might have done, but then Ismaʿil died just before his father. Or at least it looks like he did. When Jaʿfar died, one group of his followers stuck with Ismaʿil, some even arguing that his death had been faked to evade the Abbasid authorities. Eventually their allegiance fell to his son (Jaʿfar’s grandson) Muhammad. The groups that would ultimately coalesce into the Twelvers argued that Jaʿfar transferred his inheritance to one of his other sons (he had a couple). These groups eventually merged, settling on Jaʿfar’s younger son Musa al-Kazim (d. 799).

The group that followed Muhammad b. Ismaʿil split again following his death, sometime in the 810s. One group (the “Seveners”) argued that Muhammad (the seventh imam by their counting) was the final imam and also the Mahdi, and that he had not died but rather went into a sort of divine stasis, from which he would come again on the Day of Judgment. But another group, which only emerged publicly around the turn of the 10th century, claimed that they were descended from Muhammad b. Ismaʿil and had continued the line of imams in secret since Muhammad’s death. Whether this claim is true or not remains a matter of some debate. It was pretty easy to concoct a fictional genealogy in the 9th century, and yet we don’t have any conclusive evidence that they were faking it.

Employing a cadre of missionaries and an army that was largely Berber at first, this line of imams conquered first North Africa (in 909) and then Egypt (in 969) and later parts of Syria from the Abbasids. They called themselves the Fatimids, named for Muhammad’s daughter and Ali’s wife, Fatimah, from whom they traced their descent. They declared themselves caliphs, in a direct political challenge to the Sunni Abbasids. Al-Hakim (a shortened form of his regal title, “al-Hakim bi-Amr Allah,” or “Ruler by the Command of God”) was the sixth Fatimid caliph, and the sixteenth Ismaʿili imam of this particular line.

Most of the narrative of al-Hakim’s madness (eccentricity or arbitrariness, if you want to tone it down a little) revolves around his very uneven treatment of non-Shiʿa faiths, but he did some other questionable stuff in other arenas. He tried to outlaw music and dancing (good luck with that), to name one odd thing. Most infamously, he once ordered the slaughter of every dog found in the city of Cairo because their barking got on his nerves. He seems nice, in other words. The unevenness in his religious policies applied to Sunnis as well as to Jews and Christians. For example, in 1005 he ordered that major figures from Sunni history, like Muʿawiyah, Abu Bakr, and Umar, should be cursed in public. A couple of years later, he ordered the cursing to be stopped, with no apparent reason for the change of heart.

Which brings us to the matter at hand, al-Hakim’s order to destroy the most important Christian church in Jerusalem and one of the most important in the world. In the early part of al-Hakim’s reign, Jews and Christians were actually treated pretty well, arguably better than Sunnis. But starting in about 1004, he began to treat them progressively worse. He outlawed their holidays, outlawed the use of wine in religious services, forced them to start wearing identifying clothing (always a sign of good things to come), and may even have instituted forced conversion. The destruction of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre came as part of a general order to destroy Christian and Jewish places of worship throughout Fatimid domains, which was not only a stunning order in its own right, but arguably (and I’m not even sure it’s an argument) was in direct violation of Islamic law regarding the treatment of “People of the Book.”

Though he turned on Christian and Jewish worship sites in general, al-Hakim seems to have been particularly enraged about the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, which covers the site (again, allegedly) where Jesus was crucified and the site of his tomb. Hence its great importance to Christians all the way to the present day and its status as one of Christianity’s most important pilgrimage sites back in the 11th century. Specifically, it’s said that al-Hakim was angry over the church’s annual Easter vigil “Descent of the Holy Fire” ritual, which is probably done using white phosphorous-er, I mean, is a miracle, obviously. Al-Hakim saw the ritual as a fraud perpetrated on worshipers—a belief he shared, by the way, with later Catholic popes (only Orthodox Christians hold to this particular “miracle”).

Around 1012, after a couple of years of heavy persecution, al-Hakim’s behavior toward his Jewish and Christian subjects abruptly changed again. He eased restrictions on their worship and rebuilt many of the churches and synagogues he’d had destroyed. This did not include the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, though, which didn’t get rebuilt until the middle of the 11th century, after al-Hakim’s disappearance (see below). Al-Hakim even allowed those who had been forcibly converted to Islam to return to their former faiths, which in another context could have been seen as apostasy and punished with execution. As with his other wild changes of mood, this one is also unexplained.

Al-Hakim may have been influenced by a new reform movement that was developing at the time under his chief missionary, Hamza b. Ali, called al-Muwahiddun or “the Monotheists.” Heavily influenced by Greek philosophy, Hamza taught a “pure” monotheism that partly rejected the differences between the Abrahamic faiths (there was much more to it than that, obviously, but I’m not going to digress that far). Al-Hakim fostered this unitarian movement and encouraged Hamza’s preaching (some scholars claim that he became convinced that God had specifically chosen him to sort of midwife this new religious movement), and in return Hamza and his followers held the caliph in high esteem.

One of the most prominent of those followers was a man named Muhammad b. Ismaʿil al-Darazi, who broke with Hamza and began teaching that al-Hakim was not chosen by God, but was in fact an earthly incarnation of God. Although this teaching was rejected, and al-Hakim had Darazi executed for preaching his heresy, later opponents of the Muwahiddun movement slandered them by saying that this was what they all actually believed, and by naming the whole movement after Darazi, and that’s how the Druze religion got its name.

Gradually al-Hakim began to withdraw into asceticism, until one day in 1021 he went out for an evening donkey ride (as was his habit) and never came back. His most ardent supporters believed that he had been taken bodily to heaven by God, but the preponderance of evidence, including some bloody clothes found later with his donkey, suggests assassination, probably at the behest of his sister, Sitt al-Mulk (d. 1023), who then got to serve as regent to her nephew, Ali al-Zahir (d. 1036) and repealed many of al-Hakim’s more bizarre edicts (she also instituted a policy of strictly persecuting the Druze). Whatever happened to him, al-Hakim packed a lot of living into his 36 years, and made life alternately joyful and terrible for a lot of people.

Christians throughout Europe reacted to the horrible news of the destruction of one of their most cherished churches—coincidentally close to the apocalypse-tinged end of the first millennium, no less—the way that medieval Christians reacted to most horrible news (or to most good news, or, hell, to the rising of the sun each morning): by punishing Jews. No, really. Even though al-Hakim had Jewish houses of worship destroyed right alongside Christian ones, somehow Christians back in Europe figured that the Jews were to blame for the church’s destruction. A French monk named Rodulfus Glaber, displaying a crazy streak that would have rivaled al-Hakim’s, theorized that French Jews must have somehow sent a message to al-Hakim telling him to destroy the Church, lest Christians one day conquer his caliphate, or something. Al-Hakim then obeyed their message because…of the Jews’ mind-control powers, I guess? Rodulfus doesn’t even really blame al-Hakim very much for the act that he personally ordered.

Another French monk (what is it with these guys?) named Adémar de Chabannes didn’t even bother concocting a crazy story like Rodulfus. He simply argued that the destruction of the church was a sign that the End of Days was nigh, and the Jews were just as guilty as the Muslims of being agents of Satan, or whatever, so they had to be punished. Anyway, you’ll I’m sure be stunned to learn that pogroms against Jewish communities all over Europe ensued.

Aside from providing a convenient excuse for persecuting Jews, something that—let’s be honest—European Christians would have been doing anyway, the destruction of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre also had one other major impact on European Christianity. After the Battle of Manzikert (1071) put the Byzantine Empire in mortal danger, Pope Urban II issued his call (1095) for a Christian Crusade to the east to defeat the Turks and save the Byzantine Empire. It would be going too far to suggest that the destruction of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre almost 90 years earlier was foremost on Urban’s mind, particularly since the church had long since been rebuilt and since capturing Jerusalem only became the Crusaders’ main goal after their campaign was already underway. But there’s no question that the protection of Christian pilgrimage sites, something that hadn’t really been much of an issue prior to al-Hakim, had now become a major concern for the Church, and that concern helped formulate the Crusading movement.