Today in Middle Eastern history: a bad day for the Crusades

The 1291 fall of Acre marked the end of the Crusading movement.

If you’re interested in history and foreign affairs, Foreign Exchanges is the newsletter for you! Sign up for free today for regular updates on international news and US foreign policy, delivered straight to your email inbox, or subscribe and unlock the full FX experience:

There are no fewer than three Crusades-related events we can talk about today that either involve Crusader crimes against humanity or major Crusader defeats. Let’s go in chronological order.

First up is the Worms Massacre, which illustrates that some of the worst impacts of the Crusading movement fell not on Levantine Muslims but on European Jews. If you recall the utter failure of the “People’s Crusade,” then you’ll recall that the whole affair started as a result of Peter of Amiens, or Peter the Hermit, the charismatic preacher who delivered Pope Urban II’s call for Crusade throughout Europe. While Peter’s targets were important nobles who could deliver companies of well-armed, well-trained knights to the cause, he also wound up attracting a very large following among Europe’s poor and its minor nobility, many of whom joined him despite having few weapons and generally little training in military matters.

Not all of Peter’s devotees were able to join him right away, however. Some groups of would-be Crusaders sprang up in Peter’s wake, after getting their affairs in order, and set out intending to catch up to his ragtag “army.” But without Peter there to channel their zeal, most of these groups decided to skip the journey to the Holy Land and help out by killing some Jews at home instead. It must be said that they did this despite the disapproval of the Catholic Church and absent any statement—at least any that we know of—from Peter authorizing such actions.

One of the most infamous of these mobs formed around a minor Rhineland noble named Count Emicho of Leiningen. Emicho took Peter’s message and built upon it, telling people that he’d personally been visited by Christ, who commanded him to assemble an army and bring about the End of Days by first capturing Constantinople—making himself the apocalyptic “Last Emperor”—and then uniting eastern and western Christian armies in the conquest of Jerusalem. Emicho assembled an army of maybe 10,000 men in April 1096 and then sent groups of it throughout Germany to forcibly convert or kill every Jew they found. Why? Probably because he needed money to pull off his…oh, let’s call it “eccentric” scheme, and in accordance with longstanding antisemitic tropes Jewish communities in Germany were erroneously thought to be wealthy. Religion also made them a convenient target, of course, since they denied Christ’s divinity just as the far-off Muslims did.

The upshot for today’s purposes is that on May 18, 1096, a group of Emicho’s men arrived in Worms and began to spread rumors that the Jews living there were poisoning the city’s water supply. They whipped the city’s Christians into a frenzy and over the next several days wound up killing around 800 Jews (including many who took refuge in the residence of the local bishop) who refused baptism. Emicho personally led a larger massacre at Mainz about a week later, but his “crusade” finally fizzled out when the King of Hungary outright barred the ragtag mob from crossing his territory. Struggling to get to Constantinople under Hungarian harassment and running out of food, Emicho’s “army” finally scattered and he returned home.

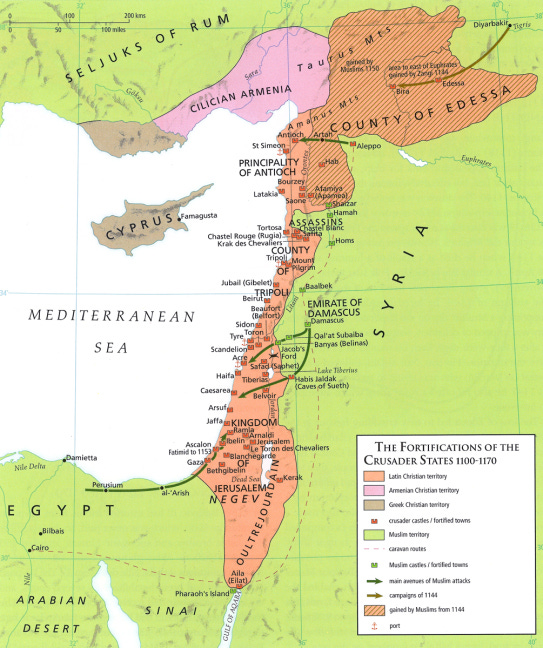

Moving into the Levant, we encounter two sieges that ended on the same date 23 years apart: the Siege of Antioch (1268) and the Siege of Acre (1291). The loss of Antioch was a significant blow to the Crusading movement, while the loss of Acre meant the end of the Crusader presence in the Middle East. The fall of both cities can be traced to a decision made by Bohemond VI (d. 1275), the prince of Antioch, to ally with the invading Mongols in the 1250s—following the lead of his father in-law, King Hethum I (d. 1270) of Cilician Armenia. After the Mamluks defeated the Mongols at Ayn Jalut in 1260, new Mamluk Sultan Baybars (d. 1277) targeted Antioch, both to punish it for allying with the Mongols and out of what appears to have been a genuine desire to rid the region of all those irritating Christian statelets.

After capturing a number of Crusader-held cities (including Arsuf, Caesarea, and Haifa) and attacking Cilician Armenia in the mid-1260s, Baybars laid siege to Antioch in May 1268 and took it after only about four days. Antioch, the first Crusader state, was a shell of what it had once been, weakened by conflicts with the Armenians and by internal political disputes. Bohemond VI didn’t even live there; he opted to make his court in his other major holding, the County of Tripoli to the south. Baybars ordered the destruction of Christian holy sites in the city and had every Christian denizen either killed or sold into slavery, then boasted of what he’d done in a letter to Boehmond. Antioch didn’t completely depopulate, but the destruction wrought by the Mamluks was thorough enough that it didn’t recover its stature as a major city until a few centuries later under the Ottomans. Today the ruins of the old city lie outside the modern city of Antakya, Turkey.

The fall of Antioch prompted Louis IX of France to launch the Eighth Crusade in 1270, which was supposed to solidify the Crusader foothold in the Holy Land by capturing…Tunis (needless to say it didn’t work). The Ninth Crusade in 1271-1272, led by the future Edward I of England, sought to make up for the Eighth’s failure and aid the Crusaders by, for starters, actually sailing to the right place. Edward, who had an excellent military mind, won a number of small raiding victories against the Mamluks and also got the Mongols to engage in several raids against Mamluk cities in Syria. But ultimately he lacked the numbers to attempt any large operation that might materially improve the Crusaders’ circumstances. His army’s presence at Acre, however, did cause Baybars to rethink a planned siege of that city and probably bought the Crusaders there almost two decades.

Ah, yes, about that. Acre’s fall on May 18, 1291, was the culmination of Baybars’ mission to drive the Crusaders (the “Franks” as Muslims called them) out of the Holy Land altogether. Though Baybars died in 1277, the Mamluk ruler al-Mansur Qalawun (d. 1290)—who was the power behind the throne for two of Baybars’ sons before taking the throne for himself in 1279—continued his predecessor’s Crusader Eradication Program. It was Qalawun who finally defeated the County of Tripoli in 1289. Bohemond VI, of course, wasn’t alive to see it, and it’s his daughter, Lucia, who has the distinction of being the last Count(ess) of Tripoli.

Acre was still nominally the seat of the “Kingdom of Jerusalem,” though the king, Henry II (d. 1324), was also king of Cyprus and had left Acre in the 1270s to locate his court on the (much safer) island. It was also the last Crusader state left, the Mamluks having eliminated the others. Qalawun made peace with Acre in the 1280s in order to focus his attention on other Crusader cities, but a massacre of Muslims inside the city, followed by a massacre of Muslim merchants near the city by a group of Venetian knights, gave him the pretext he needed to declare the treaty void. He led his army toward the city and…died in November 1290, before it was fully besieged. He was succeeded by his son, al-Ashraf Khalil (d. 1293), who brought men and siege machinery from all over the Mamluk sultanate in order to ensure the success of what promised to be the final battle to drive the “Franks” out of the region.

The siege began in earnest on April 5, 1291. Appeals from Acre back to Europe for reinforcements fell mostly on deaf ears; the zeal for Crusading had been superseded by gthe urgency of intra-European affairs. Henry II arrived with reinforcements from Cyprus, but they weren’t nearly enough to counter the army that Khalil had amassed. The Crusaders offered to make restitution for the aforementioned massacres, but when Khalil demanded Acre itself as said restitution that kind of brought the negotiations to a halt.

Finally on May 18, a heavy assault by the Mamluks on one of Acre’s towers proved successful, and the city fell as its inhabitants fled for the docks in panic to try to board ships heading to Europe. The last holdout proved to be Acre’s Templar office, which took in refugees and was defended ferociously by the remaining Templar knights. On May 28, during an assault by a company of Mamluks, the structure collapsed, killing the refugees, the Templars, and many of the attackers.

After Acre fell, Cyprus continued to serve as the seat of the now even more farcical “Kingdom of Jerusalem.” That pretense was all but put to rest when the Venetians took control of the island in 1473, and certainly when the Ottomans took it from Venice in 1570. A new crusade to restore the Christian presence in the Holy Land was sometimes talked about, but never actually came to fruition. A small Templar fortress on the Isle of Ruad (modern Arwad, Syria) fell in 1303, which made a hypothetical Christian invasion of the Levant logistically dubious. And European rulers were simply too entangled in continental affairs to focus on Crusading again.

This is not to say that the concept of the “crusade” died completely, but its meaning did change. Among these attention-grabbing continental affairs was the rise of the Ottomans in the late 14th century, which put Europe squarely back on the defensive when it came to Islam. From then on, and for several centuries to come, most talk of “crusade” would involve operations to defend Europe from the Ottomans.