Today in Iranian history: the Shahnameh is completed (1010)

Abu’l-Qasim Ferdowsi’s epic became one of the most frequently copied literary works in history and is credited with helping to revive the Persian language.

If you’re interested in history and foreign affairs, Foreign Exchanges is the newsletter for you! Sign up for free today for regular updates on international news and US foreign policy, delivered straight to your email inbox, or subscribe and unlock the full FX experience:

Obviously there are a lot of important works of literature that have been created over the years and across the many cultures of the world, so if I were to describe Abu’l-Qasim Ferdowsi’s Shahnameh as simply a great work of literature I would be doing it something of an injustice. It is a great work of literature, but its importance to history runs deeper than that. It has been argued that this epic is responsible for saving Iranian civilization and the Persian language from extinction—or, at least, from being completely marginalized. On its face of course that sounds completely hyperbolic, but in fact you really can make a pretty strong case that Ferdowsi, through the Shahnameh, preserved fundamental aspects of pre-Islamic Iranian culture (especially the language) that were on the brink of being lost. This is not to say that Ferdowsi did all that single-handedly, but he and his epic were instrumental in the effort.

Traditional Iranian culture was overwhelmed in the wake of the seventh century Arab conquests and the imposition of Islam throughout the lands that had previously either belonged to, or existed within the orbit of, ancient Persia. The successive empires that ruled the region from Iraq in the west to modern Afghanistan in the east built a cultural powerhouse over the ~15 or so centuries they were around (8th century BCE to 7th century CE), one that was strong enough to absorb the massive disruption of Alexander the Great’s conquest and, while admittedly having been changed by the experience, to keep on keeping on. Like Alexander, the Arab conquests didn’t just usher in a new ruling dynasty or a new military power. They brought an entirely new heritage from an entirely alien civilization that was based on an entirely different language. Unlike Alexander, whose Hellenism was absorbed into Iranian civilization as his Greco-Macedonian successors faded from history, the most important change the Arab conquerors wrought—the arrival of Islam—never faded and indeed came to dominate Iranian society moving forward.

In some small ways Islam wasn’t entirely foreign to Iran. Zoroastrianism, the major faith of pre-Islamic Persia, influenced Second Temple Judaism, and therefore it influenced the development of Islam. But Zoroastrianism was not a part of the Abrahamic tradition. The new Arab rulers worshiped God (Allah in Arabic, of course), not Ahura Mazda—though the two were conflated somewhat in the use of the Persian word khuda (“Lord”) to mean “God”—and they traced their ancestry back to Adam and Abraham, not mythical Persian kings like Keyumars and Jamshid. They had an entirely different way of looking at the world and its history, one that couldn’t easily co-exist alongside its Zoroastrian counterpart.

There’s no evidence that early Muslims sought to forcibly convert Zoroastrians to their developing new faith. In fact, Zoroastrians were usually considered one of the legally (if not always actually) protected Peoples of the Book, like Christians and Jews. This classification raised some eyebrows among Muslim scholars, since the Quran doesn’t say anything about Zoroastrians being a protected class, as it does for adherents to the other Abrahamic faiths. But it was, if nothing else, a concession to the fact that (initially) there were a whole lot more Zoroastrians in Iran than there were Muslims. Still, conversion happened nonetheless, either out of a genuine religious sentiment or a practical awareness that, in order for one to thrive in an Islamic empire, it became necessary at some point to embrace Islam.

So Iranian culture was subordinated, then ignored. While some form of spoken Persian undoubtedly survived, Arabic became the language of literature, religious observation, and polite speech. Written Persian was largely forgotten, and spoken Persian vernaculars borrowed heavily from Arabic vocabulary. Zoroastrian religious texts were gradually lost, even though Zoroastrianism continued to be (and continues to be) practiced (albeit by a dwindling group of followers). And the legends and histories (the line between the two was blurry, as was the case for most ancient cultures) that had shaped the Iranian sense of self were mostly put aside in favor of the stories of the Quran and the Abrahamic tradition. Things stayed this way for a couple of centuries, give or take. Around the end of the 8th century, though, a movement called the Shuʿubiyah developed that sought to protect local linguistic (and thus literary and cultural) traditions that were in danger of being totally snuffed out by Arabic. As probably the most important non-Arabic language in the caliphate, Persian became a particular focal point for this effort.

The Shuʿubiyah required political change in order to get any traction, and that happened in the 9th century, when the Abbasid caliphate was looking less like a unified empire than a collection of independent kingdoms all paying homage to the caliph in Baghdad. Unsurprisingly, a few of these kingdoms developed in the Iranian east. One, the Samanid Empire (819-999) gets credit for bringing the Persian language and Iranian culture out from the limbo they’d been in since the Arab conquests. They used Persian at court and, more importantly, they patronized writers who worked in “New Persian,” which was the old Persian language augmented with some Arabic vocabulary and adapted so that it could be written using the Arabic alphabet. The Arabic alphabet and the Persian language don’t mesh terribly well if you ask me, but if you wanted to get anything written down (especially by a professional scribe) in 9th century Iran you didn’t really have a lot of alphabetic options available to you.

The first great literary figure to benefit from Samanid patronage, or at least the first one whose works have survived to the present day, was a man named Abu Abdullah Jafar b. Muhammad Rudaki (d. ~940s), who wrote vast amounts of poetry in every style of the time and is known to have translated the great Indian collection of animal fables, the Panchatantra, into Persian from Arabic, to which it had been translated by the writer known as Ibn al-Muqaffa (d. ~750s) under the title Kalila wa Dimna. Unfortunately only about 50 of Rudaki’s poems have survived, and his translation of Kalila wa Dimna is known today only in fragments.

So, to reiterate, Ferdowsi didn’t single-handedly save the Persian language, exactly, since there were other contemporary writers who were also writing in it. But it seems fairly clear that Ferdowsi was more influential than Rudaki. For one thing, the number of surviving manuscripts suggests that his work was far more widely read than Rudaki’s. And for another thing, his Shahnameh wasn’t just written in Persian, it was written about Persia. It didn’t just help preserve the language, it helped bring ancient Iranian myth into the 10th century and beyond.

Ferdowsi was born sometime around 940 in the city of Tus, then part of the Samanid Empire. We don’t know very much about his early life except that he and his family were Iranian landowners who had been part of the aristocratic class under the Sasanians and continued to hold some importance even after the Arab conquest. He began work on the Shahnameh in 977, picking up where a previous poet, Abu Mansur Daqiqi, had left off before he was murdered (supposedly by one of his servants—the whole thing sounds very scandalous). Daqiqi had set out to translate a Sasanian chronicle called “The Book of Kings” (hence the title, Shahnameh, which means exactly that) into verse in the new Persian, again on behalf of (and hopefully in return for payment from) the Samanid court. Daqiqi may have been working from a prose version of the Sasanian text that had been updated into New Persian—Ferdowsi alludes to something like this in the introduction to his epic—but if so, that text has been lost to history.

Initially Ferdowsi worked (according to his introduction) under the patronage of a Samanid prince named Mansur, but then the Samanid kingdom was conquered by the Turkic Ghaznavids in 999. Undaunted, Ferdowsi replaced his lost patron with none other than Mahmud I of Ghazna (d. 1030), which was definitely an upgrade, prestige-wise. He finally completed the work on March 8, 1010, give or take.

Legend has it that Mahmud promised to pay Ferdowsi a gold coin for every couplet in his text. But the official he sent to deliver the money, who hated Ferdowsi and regarded him as an apostate after reading the Shahnameh and its sympathetic (in the official’s view) depiction of Zoroastrianism, swapped these for silver coins, worth substantially less. Insulted, Ferdowsi basically gave the coins away to the first three people he saw. When Mahmud (who still thought he’d paid Ferdowsi in gold) heard of this he was enraged. And that was before he learned that Ferdowsi had written a whole new poem mocking his erstwhile patron. Ferdowsi had to flee into an exile whose length is unclear, although we know he returned home at some point because that’s where he died. Supposedly Mahmud learned of the official’s treachery in 1020, had him executed, and sent the correct payment to Ferdowsi’s home in the city of Tus—where it arrived just in time to meet the poet’s funeral procession.

The Shahnameh itself is an epic in the truest sense of the word, delving back into the most legendary corners of Iranian myth and history. It has much to say on the nature of man, the nature of justice, the proper use of royal authority, charity to the poor, devotion to family, and, crucially, what it means to be Iranian. It revives the idea of a geographic Iran, Iran-zamin, which became the historical model for later Iranian kingdoms and, eventually, for modern Iran (although we should note that Iran-zamin is substantially bigger than modern Iran). And, yes, it does treat Zoroastrianism sympathetically, but I don’t think you could conclude from reading it that Ferdowsi was a crypto-Zoroastrian or anything like that (his introduction includes a section written in praise of Muhammad and Ali, for example, which doesn’t exactly mesh with Zoroastrian orthodoxy).

Again, Ferdowsi wasn’t the first to write in modern Persian, but the Shahnameh helped to fix modern Persian in the form we know today, in part because the text was copied over and over again by various Iranian dynasties that followed. Many manuscripts have survived, at least in partial form, and they are among the most highly-prized examples of Persian book arts and miniature painting that still exist. Later Iranian rulers commissioned copies of the text as personal treasures, as dynastic heirlooms, and as propaganda pieces about the majestic history of the Iranian people (these would be given as “gifts” to rulers of neighboring kingdoms). So, like I said earlier, its importance goes far beyond the literary. I wouldn’t put it on the level of a defining religious text like the Torah, the Gospels, or the Quran, but it’s not far off from that. It can definitely be placed next to works like the Aeneid, Beowulf, or Homer’s epics in terms of its societal importance.

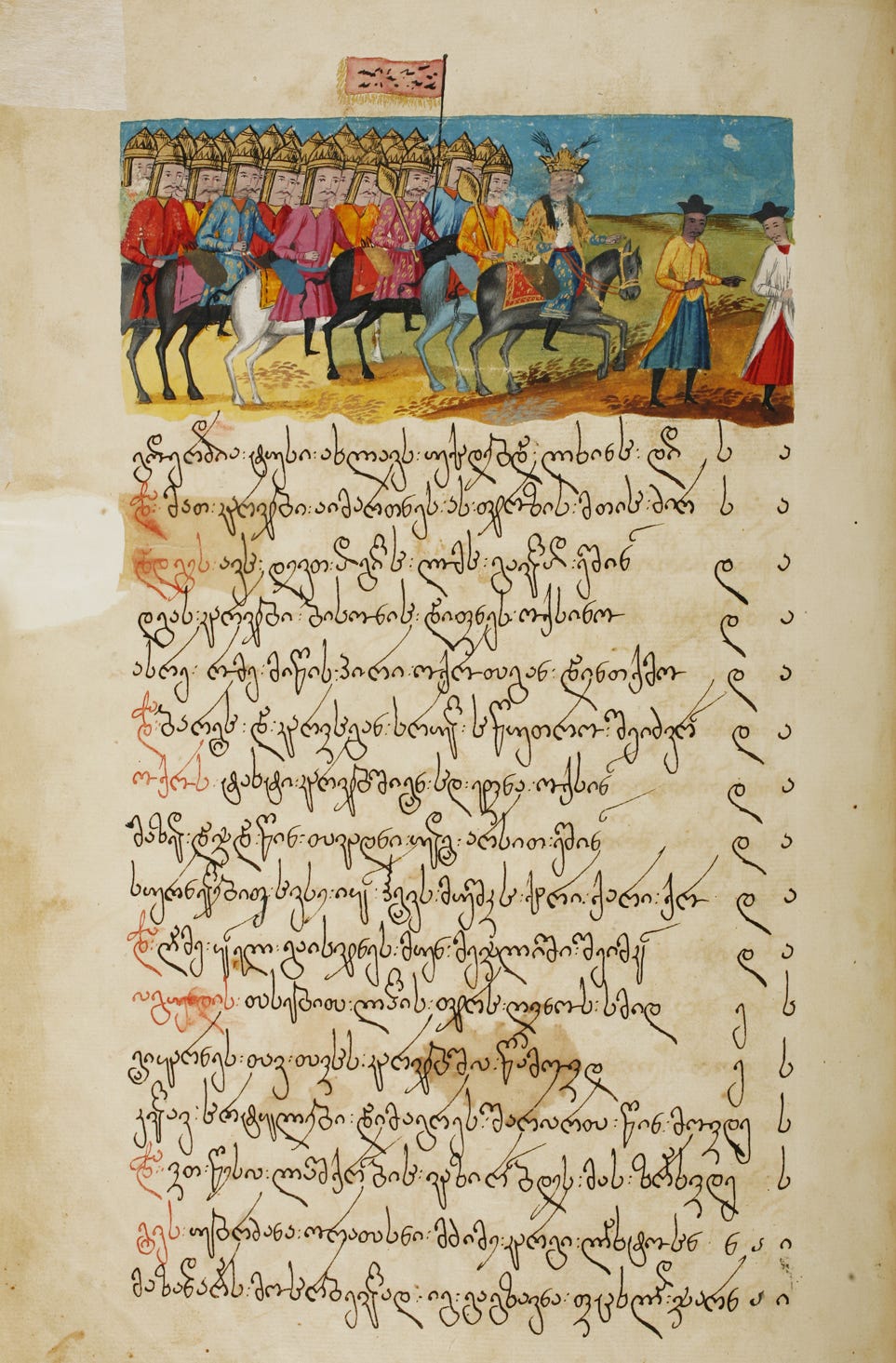

The Shahnameh’s influence stretched beyond Iranian civilization, and there are artifacts of it that can be found in many other traditions—particularly in Georgia (see above), where the epic’s stories embedded themselves in Georgian literature. The “Turanians,” which the poem depicts as Iran’s traditional enemies (and agents of Ahriman, the Zoroastrian equivalent of Lucifer) are often identified as ancient Turks, and Turkic groups in Central Asia have at times self-identified as descendants of the Turanians.

It’s likely that the “real” Turanians, to the extent they can be called “real” and not mythical, were nomadic and (probably) non-Zoroastrian Iranian peoples, not Turks. They inhabited parts of Central Asia that later were conquered by Turkic peoples, at which point identities became conflated. But the “Turanian=Turkic” link makes for a nice story, anyway, and it’s stuck around for centuries (“Turanism,” or “pan-Turanism,” is a modern political movement that calls for unity among all peoples with roots—real or imagined—in Central Asia). For English speakers, there’s a great translation of the work by Dick Davis that you can pick up pretty much anywhere, and if you enjoy mythology at all, even if you have no interest in the Middle East or Iran, I’d highly recommend checking it out.