Today in European/Middle Eastern history: Frederick Barbarossa drowns (1190) and more

The Third Crusade starts to go sideways, along with a few other noteworthy anniversaries.

If you’re interested in history and foreign affairs, Foreign Exchanges is the newsletter for you! Sign up for free today for regular updates on international news and US foreign policy, delivered straight to your email inbox, or subscribe and unlock the full FX experience:

Some days there are a bunch of little historical anniversaries to commemorate, but none that of themselves seem to warrant their own post. June 10 is one of those days. We’ve got four different anniversaries to note, so let’s take them in chronological order.

1190: Frederick Barbarossa drowns

On June 10, 1190, Holy Roman Emperor Frederick I, or Frederick Barbarossa, shuffled off of this mortal coil at the age of 68 (give or take). To be more specific, he drowned while attempting to cross the Saleph River (now called the Göksu River) near Silifke Castle in southern Anatolia. It’s not clear what exactly happened, but it would appear that Frederick’s horse threw him off while crossing the river. Due either to the weight of his armor or to the weight of his armor plus a sudden heart attack, the emperor drowned in what was actually pretty shallow water. Tragic, right? Anyway I’m not noting this because I’m fond of old Holy Roman Emperors, but because Frederick’s failure to properly ford a river contributed greatly to the much larger failure of the Third Crusade.

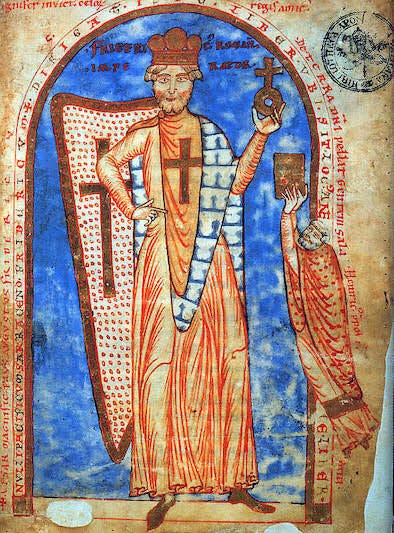

Frederick all dolled up in his ill-fated Crusading costume (Wikimedia Commons)

The Third Crusade was led by Richard the Lionheart (d. 1199), with his English army, and France’s Philip II (d. 1223), with his, you know, French army. But it was supposed to be a three-way affair also involving Frederick and an imperial army whose size remains a bit of a mystery. After he drowned, reports had it that he was leading a massive 100,000 man force to liberate Jerusalem from Saladin. But those accounts were probably inflated to emphasize the tragedy of his death, and it’s far more likely that he was leading an army a fifth or less of that size. Whatever the size of Frederick’s army was while he was still alive, most of it dissolved shortly after his death and only a small remnant eventually made it to the Holy Land under the command of Duke Leopold V of Austria (d. 1194).

A full German army, and maybe Frederick himself, sure would have come in handy in the middle of 1191, when Philip packed up most of his army and abandoned the Crusade to return to France. He was angry that Richard was overshadowing him, angry that Richard had refused to marry Philip’s sister (to whom he had been betrothed for some time), angry that Richard supported Guy of Lusignan’s claim to the Jerusalem throne (Philip backed rival claimant Conrad of Montferrat), and keen to go home and see if he could seize England’s continental possessions while Richard was still in the Middle East. Leopold, who also backed Conrad and was angry at being treated like a junior partner just because he was a duke among kings, left too. Without most of the French and German forces, Richard lacked the manpower to successfully besiege Jerusalem. He decided to turn his attention to Egypt, but his men nearly revolted and demanded to march on Jerusalem as planned. At that point, Richard told his army that he would gladly march with it to certain death before the walls of Jerusalem, but he would not be responsible for leading it to that defeat, and the crusade fizzled out.

Frederick was succeeded by his son, Henry VI (d. 1197), who was crowned emperor by Pope Celestine III in April 1191. It was Henry, along with Leopold, who later imprisoned Richard while the English king was returning from the Holy Land, and ransomed him back to England for a massive sum (a literal king’s ransom, you might say). Had Frederick lived, perhaps he and his army would have stayed in the Holy Land and the Crusaders would have been enough to take Jerusalem. Maybe he would have even been able to mediate the dispute between Richard and Philip. We’ll never know.

1329: The Battle of Pelekanon

The Battle of Pelekanon took place on June 10-11, 1329 between a Byzantine army led by Emperor Andronikos III Palaiologos (d. 1341) and an Ottoman army led by their ruler (Ottoman rulers weren’t using the title “sultan” yet) Orhan I (d. 1362). The Byzantines were attempting to relieve Ottoman sieges of both Nicomedia (modern İzmit) and Nicaea (modern İznik). They were outnumbered by the Ottomans but the Ottoman military at this point was limited to very irregular light cavalry while the Byzantines sported a professional military with knights and the whole shebang. Nevertheless, the Ottomans were able to outmaneuver the Byzantines and defeat them decisively.

Orhan I (Wikimedia Commons)

It sounds weird to say because it wasn’t a particularly large clash and the Byzantine Empire lasted for another ~120 years after Pelekanon, but the battle turns out to have been their last chance to hold the Ottomans off and keep their remaining Anatolian territory. Nicomedia and Nicaea both fell to the Ottomans in the 1330s, and from Pelekanon on the Byzantine-Ottoman conflict played out mostly in Europe.

1805: The First Barbary War ends

June 10, 1805, saw the end of the First Barbary War between the United States and the Barbary States, primarily Tripolitania (northwestern Libya nowadays). The war had started in 1801 over Barbary pirate attacks on US shipping in the Mediterranean. It ended with the US blockading Tripoli, a US-led mercenary army having just captured Derna and threatening to attack Tripoli by land, and with Tripolitanian ruler Yusuf Karamanli (d. 1838) facing rumors of a coup against him. The US agreed to pay ransom for sailors that the Tripolitanians had captured and in return the piracy against US vessels was supposed to cease. It did not, which is why the US fought the Second (and considerably shorter) Barbary War against Algiers in 1815.

1916: The Battle of Mecca begins

Finally, June 10 marks the beginning of the Battle of Mecca, and therefore of the World War I Arab Revolt, in 1916. This was the result of months of correspondence between Sharif Hussein of Mecca (d. 1931) and British High Commissioner for Egypt Henry McMahon (d. 1949) in which McMahon flattered Hussein, whose ego had been bruised by the Ottoman government, and made promises of a post-war, pan-Arab kingdom under Hussein’s rule that Britain had no intention of ever keeping. The battle took almost a month, as even though Hussein’s forces vastly outnumbered the Ottoman garrison the Ottomans were better armed and much better trained. The introduction of British forces from Egypt eventually turned the tide. The battle did considerable damage to Islam’s holiest city, which Hussein blamed on the Ottomans and thereby gained crucial support for his revolt across the Arab world.