Today in European history: the (third) Siege of Algeciras ends (1344)

The Kingdom of Castile captures one of the most important seaports on the Iberian peninsula.

If you’re interested in history and foreign affairs, Foreign Exchanges is the newsletter for you! Sign up for free today for regular updates on international news and US foreign policy, delivered straight to your email inbox, or subscribe and unlock the full FX experience:

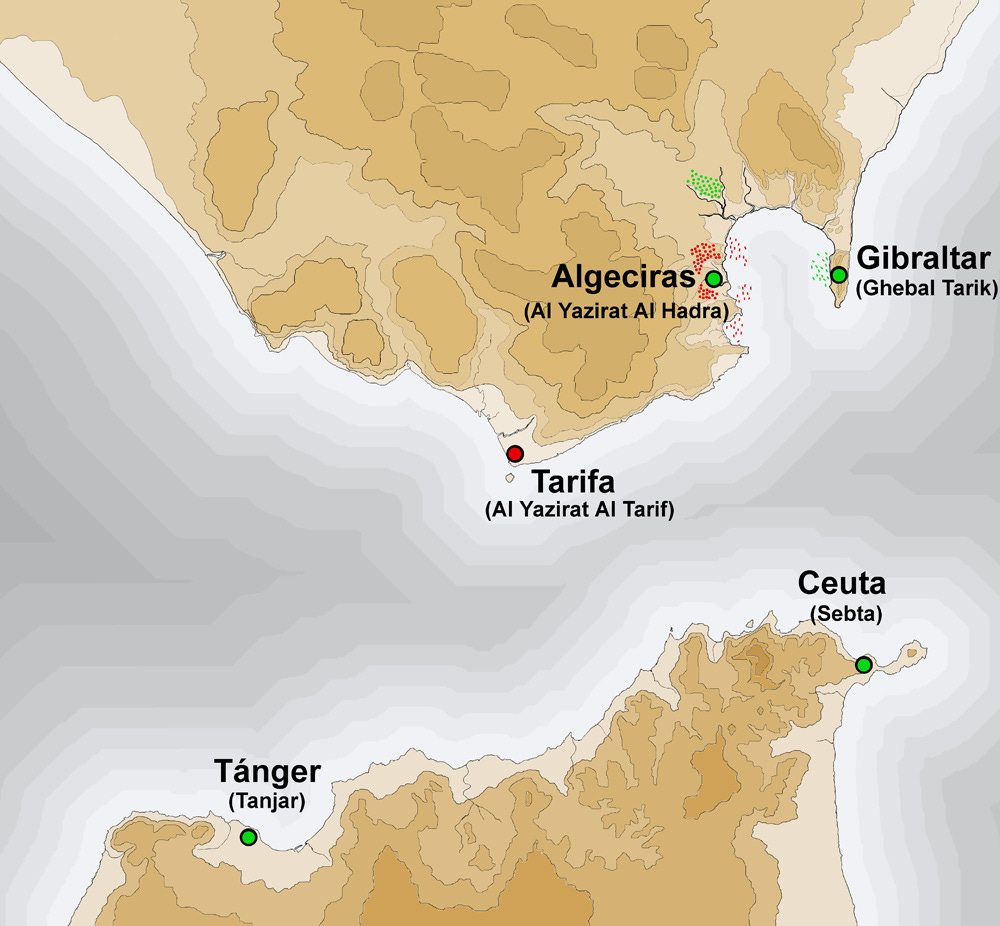

Modern Algeciras is the main city on the Bay of Gibraltar and one of the busiest commercial ports in Europe. It’s pretty old, too, having been founded by Berber-Arab invaders all the way back in 711. “Algeciras” is a European corruption of the city’s original name, al-Jazirah al-Khadra (“the green island”). And, if we’re being totally comprehensive, those Muslims only rebuilt a city that had previously been a major Roman port before it was destroyed by Germanic invaders. Today we’ll be discussing that key port city’s conquest by the forces of the Kingdom of Castile.

They say the three rules of real estate are “location, location, location,” and I suppose that’s as true when you’re looking for a city to conquer as it is when you’re looking to buy a house. Algeciras was in an incredibly important location that made it a hub both for commerce and for the transit of human beings (often heavily armed human beings) from North Africa into southern Iberia—or al-Andalus, as it was known at the time. So for the various Christian dominions participating in the so-called Reconquista, capturing Algeciras was a major goal. That’s why this 1342-1344 episode was the last of three Christian sieges of the city undertaken in the 13th and 14th centuries. The first, in 1278, ended when a relief army from Morocco broke through a Castilian naval blockade and then drove off the Christian besiegers, and the second, in 1309-1310, ended when disease ravaged the Castilian camp and forced then-King Ferdinand IV (d. 1312) to withdraw.

For this third bite at the apple, Castilian King Alfonso XI (d. 1350) wanted outside assistance. And he got it, obtaining considerable support from the Republic of Genoa (or at least from Genoese mercenaries), from Portugal, and from Aragon, in addition to knights from around Europe who had taken up the cause of the Reconquista as a Crusade. In the period since the previous siege, the Marinid rulers of Morocco had taken Algeciras from the Emirate of Granada and made it the nexus of a planned attempt to invade Iberia and reconquer the parts of al-Andalus that had already been lost to the Christians. Consequently, the Castilians were able to make the case that an attack on Algeciras wasn’t just an act of conquest, it was a defense of Christian Europe. Alfonso had already gotten a glimpse of the Marinids’ intentions, and of Algeciras’ importance, during his successful defense of Tarifa in 1340. During that operation, Marinid reinforcements from Morocco landed in Algeciras and might have made the difference in the siege if the Marinid ruler, Abu al-Hasan Ali b. Uthman (d. 1350) hadn’t proven to be, in technical military terms, a dolt.

Alfonso also decided to plan ahead. In particular, he needed to prevent the Marinids from sending supplies and potentially another relief army from Morocco, which meant he needed ships. So he started building some, and he arranged for more from his allies. These began interdicting shipments of goods from North Africa while Alfonso continued to build up his land army. When that force was ready, in late July 1342, Alfonso led it to Algeciras. They besieged it in early August. Initially things did not go well for the Castilians. Most of the Aragonese navy had to bow out of the blockade due to an impending war with the Kingdom of Majorca, which if you’re wondering ended in 1349 with that kingdom subjugated to Aragon, then Spain, for the rest of its nominal existence. Rainy weather bogged Alfonso’s besieging army down and allowed Algerciras’ defenders to engage in their favored hit and run tactic, which involved quick raids on the enemy line in hopes that the Castilians, looking to retaliate, would come close enough to the city that they’d leave themselves vulnerable to archers manning the walls. The rain also caused shortages of food and increased the prevalence of disease in the Christian camp, which was ironic since the plan had been to starve the city into submission. Hunger started to look like a greater threat to the attackers than to the defenders.

Slowly but surely, however, the Castilians made progress, digging covered trenches and erecting defensive walls to protect them as they built their siege engines. And by early 1343 fresh soldiers began arriving to replace those who had been killed or for various reasons were no longer able to fight. The Castilians were constantly facing the threat that Algeciras would be reinforced, either from Morocco or by the nearby Emirate of Granada, whose Nasrid emirs weren’t always particularly friendly with the Marinids but certainly had more sympathy for them than for the Christians. Yes, the city and the bay were blockaded, which lessened the chances of a relief army getting through, but the Aragonese, Portuguese, and Genoese ships that maintained the blockade were constantly coming and going depending on the needs of their own home principalities (and, with respect to the Genoese, depending on whether Alfonso could keep paying them). So in addition to covering the land approaches to and from Algeciras, the Castilians tried to speed things along with the copious use of artillery—specifically, trebuchets launching heavy stone balls. The city’s defenders returned fire using bombards, or early cannon, and this siege actually marks the first time that gunpowder weapons were used in Iberia (and one of the first times they were used anywhere in Europe).

As it turns out, both Morocco and Granada came to Algeciras’ aid. In October 1343, a very large (perhaps around 50,000 men) relief army embarked from Morocco to come to the city’s aid. The blockade held, albeit only after Alfonso agreed to make a hefty overdue payment to the Genoese, but the Moroccan army was still able to land at nearby Gibraltar. It met up with a Granadan army and marched toward Algeciras. Some kind of battle was inevitable, and the Castilians redoubled their artillery fire to try to bring the siege to an end. They were able to breach the walls in early December, but couldn’t exploit the breach and wound up facing the combined relief army in what’s known as the Battle of the River Palmones on December 12. This wound up being not much of a battle, to be honest. The Castilians were able to overwhelm the Marinid-Granadan army as it crossed the river and rout it.

At that point the siege became a race against time. The Marinids and Nasrids could still reform their army and attack again, but given how disorganized their retreat had been that would take a while. They tried diplomacy instead, but Alfonso was set on capturing Algeciras and rejected negotiations. The people inside Algeciras were starving, but small supply ships from Gibraltar were getting through the blockade, bringing just enough food to keep the defense going. So in January 1344 Alfonso ordered the creation of a boom across the sea approach to the city, consisting of ropes stretched across the bay, supported by empty barrels turned into makeshift buoys. By early March it became impossible for even those small ships from Gibraltar to get into Algeciras, and the defenders were forced to surrender in lieu of starving to death.

The capture of Algeciras was of considerable importance to the Christians, but largely insofar as it denied the Marinids their most important European port. The Castilians didn’t actually hold the city very long; a fourth Siege of Algeciras, this time conducted by Muslims against Christian defenders, took place in 1369. Castile at the time was mired in civil war, and so Granada, under Sultan Muhammad V (d. 1391), was able to take the city. The Castilians regrouped, however, and Muhammad opted to destroy the city in 1379, when it became clear that he wouldn’t be able to defend it. Algeciras remained defunct until 1704, when it was rebuilt by people fleeing the British conquest of Gibraltar during the War of Spanish Succession.