Today in European history: the Siege of Vienna ends (1529)

The Ottomans reach what would prove to be their territorial limit in central Europe.

If you’re interested in history and foreign affairs, Foreign Exchanges is the newsletter for you! Sign up for free today for regular updates on international news and US foreign policy, delivered straight to your email inbox, or subscribe and unlock the full FX experience:

The city of Vienna has kind of an odd but prominent place in Ottoman history. It was never part of the empire, but two Ottoman attempts to conquer it bookend the period of the empire’s greatest territorial reach and military power. The second of those attempts, the 1683 Battle of Vienna, serves as the empire’s high water mark, after which it began shedding territory. Today is the anniversary of the end of the 1529 Siege of Vienna, the first time the Ottomans tried to capture the city. While it, too, failed, its failure didn’t signal a decline in Ottoman power so much as it defined the empire’s territorial limits and led to a period of relative stasis in eastern and central Europe. It was also the first major battle of the centuries-long rivalry between the Ottomans and the Habsburgs, a rivalry that defined much of European history.

Although Vienna is of course in Austria, the campaign that led to the siege actually focused on Hungary. At the Battle of Mohács in 1526, the Ottomans defeated the Hungarian army under King Louis II, and Louis was killed. This put southern Hungary in Ottoman hands, but also left the throne of the rest of Hungary empty, as Louis had no children. Into that vacuum stepped Ferdinand I (d. 1564), the Habsburg Archduke of Austria and the brother of Holy Roman Emperor Charles V (Ferdinand would later become Holy Roman Emperor himself, but we’re not worried about that here). Ferdinand was married to Louis’ sister, and through that relationship he staked his claim to the throne. He was challenged on this point by a Transylvanian noble named John Zápolya, whose claim was supported by the Ottomans and who established what was known as “Ottoman Hungary,” a partition that survived until the Ottomans were forced to give it up in the 1699 Treaty of Karlowitz (which ended the war that included that 1683 Battle of Vienna, just to bring everything full circle).

Over the course of 1527 and 1528, Ferdinand pressed his Hungarian claims in a campaign that was fairly successful, driving Zápolya out of several cities including Buda. In 1529, Ottoman Sultan Suleyman I (AKA Suleyman the Lawgiver or Suleyman the Magnificent—he was a very popular guy) decided to put an end to this nonsense and impose Ottoman control over all of Hungary. He was also engaged in a developing alliance with Francis I of France, who loathed his fellow Catholic Habsburgs so much that he was willing to extend a hand of friendship to the Muslim Ottomans. Francis had asked Suleyman to do him a solid and attack the Habsburgs on their eastern flank, something the Ottoman ruler probably would have been doing anyway. The Ottomans formed an army that may have been as large as 125,000 men (some sources go as high as 300,000, but that seems unlikely). This army, setting out in May, rolled back Ferdinand’s gains so easily that Suleyman then decided to strike at the archduke’s own capital, Vienna. The Ottomans specialized in heavy artillery and siege warfare, so they were fully prepared to breach Vienna’s walls and take the city.

You can imagine that most of the rest of Europe (outside of France, presumably) was pretty nervous about what was unfolding here. Vienna was the westernmost major city on the Danube; if the Ottomans took it, the door to central Europe was wide open for them. From there, they could move north to pick off the various German states, south over the Alps toward Rome, west into France and Spain, or even back east into Poland and Russia (which they could theoretically have attacked from two directions at that point). Whatever grand plans Suleyman may have had were undone not so much by force of arms as by the weather.

The Balkans were drenched in rain in the spring of 1529, which created enormous (and, as it turned out, insurmountable) problems for the Ottoman army. Specifically, it couldn’t move its heaviest and most siege-worthy guns through the mud, so it had to simply abandon them along the way. The camels that the Ottomans had brought along as pack animals died in droves in the inhospitable climate. And the Ottoman soldiers themselves suffered from illness and from the general sour disposition that would hit anybody who gets tired of marching around in the mud and being rained on all day long. The slowness of the Ottoman march also allowed Vienna’s garrison, under the command of the 70 year old Nicholas, Count of Salm (who had been hired by Ferdinand to come and lead the defense), to make substantial defensive improvements and to stockpile supplies to withstand a siege, despite being at a considerable numerical disadvantage (they had somewhere in the neighborhood of 20,000 defenders). Nicholas, by the way, would die of injuries sustained during the siege, but he certainly fulfilled whatever arrangement he had with Ferdinand.

The Ottomans laid siege to Vienna beginning on September 27, but where the army that had set out in May might have been a real threat to take the city, the army that arrived before its walls in late September really was not. With his best artillery rotting in the mud along his line of march, Suleyman tried sending sappers to dig under the walls and mine them, but the Austrian defenders were able to dispose of the mines and eventually to close off the Ottoman tunnels. The Ottomans began running short on supplies and the Janissaries (who were really tired of being sick and getting rained on) started to complain that things were going nowhere and it was time to head home. Suleyman decided to order one all-out assault on the city, but with the walls still intact there was no chance that it would succeed. Stymied, the emperor elected to retreat and try again at a later time. He did try again, in 1532, but the campaign never reached Vienna—it turned around when word came that Charles V was already leading a large relief army toward the city. As we now know, that “later time” didn’t really come until over 150 years later, and it went very badly for the Ottomans.

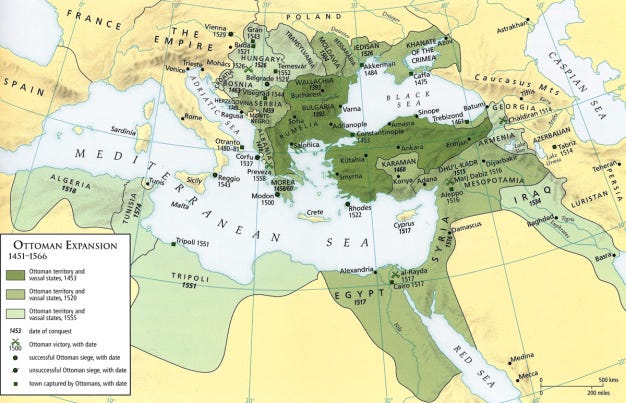

The Siege of Vienna was a setback for the Ottomans insofar as it halted their advance into central Europe, but it didn’t really do any lasting damage to the empire. In fact, the overall campaign really succeeded, since it did accomplish its initial goal of driving Ferdinand out of Ottoman-controlled Hungary. The Ottoman inability to take Vienna could reasonably be chalked up to a fluke of weather. There is a common narrative that says that this siege was the beginning of Ottoman decline, but it doesn’t hold up very well because there’s really no evidence of any “decline” for quite some time afterward. The empire remained wealthy and militarily dominant (both in Europe and in the Middle East) for decades to come. In fact, it continued to expand—just not any deeper into mainland Europe. Between this siege and the Ottomans’ second attempt in 1683, the empire had brought under its control almost all of North Africa, all of modern Iraq, much of the eastern coast of the Arabian Peninsula, and the island of Crete.

However, with the benefit of hindsight we can say that the successful defense of Vienna may well have saved Christian Europe. If the Ottomans had been able to take Vienna and turn it into their new regional base of operations, their territorial limits would have been completely redefined. Vienna stopped the Ottoman advance and gave the Habsburgs and other European principalities time to build the kind of military capacity that would eventually begin to not just ward the Ottomans off, but to really roll back their previous gains. It also caused the Ottomans to refocus their attention on controlling the Mediterranean, which proved to be harder than it looked. A history where the Ottomans captured Vienna would very likely have been a much different history than the one we actually experienced, and we can chalk it all up to the city’s defenders and, even more, to a rainier-than-usual Balkan spring.