Today in European history: the Siege of Lisbon ends (1147)

An army of would-be English Crusaders takes a detour to the Iberian peninsula and changes the course of Portuguese history.

If you’re interested in history and foreign affairs, Foreign Exchanges is the newsletter for you! Sign up for free today for regular updates on international news and US foreign policy, delivered straight to your email inbox, or subscribe and unlock the full FX experience:

There’s plenty of irony to go around when you’re talking about the Crusades, but it is especially apparent on those occasions when our intrepid armed pilgrims to the Holy Land wound up making their mark somewhere else. Obviously the best example here is the Fourth Crusade, when instead of marching off to once again “liberate” Jerusalem from its Muslim overlords the Crusaders went broke and then hired themselves out as mercenaries to sack the very non-Muslim city of Constantinople on behalf of Venice. The Eighth Crusade isn’t bad for this either, unless “dying of dysentery outside the walls of Tunis” was actually their goal. Then there’s also the Second Crusade, which is a bit less ironic than the others. Sure, it failed miserably in the Middle East, but it actually succeeded wildly in Iberia. Yes, Iberia is a ways off from Jerusalem, but in their defense (and in marked contrast to the Fourth Crusade) at least the city these guys besieged was actually controlled by Muslims.

What makes the Siege of Lisbon interesting is that it brings together for a brief time the two events to which most Western minds still turn when they think about the history of Christian-Islamic relations: the Crusades, obviously, and the Reconquista. Since it’s been a while I suppose I should renew my objection to the term “Reconquista,” which implies that Iberia is somehow Christian by right and had to be “reconquered” from the Muslims who merely squatted there for, uh, over seven centuries. Nevertheless I’ll use it here, as I’ve used it in other entries on the same subject, because that’s the term most people know and I’m not looking to reinvent the wheel here.

The Reconquista does have some things in common with the Crusades, and the Catholic Church treated them as equivalent in many respects. In fact, Pope Paschal II (d. 1118) told Iberian Christians that in lieu of going on Crusade they should stay home and fight the Muslims in their own back yard. Pope Eugene III, who assembled what we now call the Second Crusade after the Zengid Emirate captured the Crusader state of Edessa in 1144, made the equivalence quite explicit and referred to the conflict in Iberia as its own “crusade.” But although the war in Iberia was akin to a Crusade, it was mostly rough weather, rather than religious fervor, that caused a large fleet of at least 160 and probably closer to 200 ships—which had all set sail from England in May 1147 bound for the Holy Land—to stop over in Portugal along the way.

The Crusaders who set out from England seem to have been a fairly motley bunch, without so much as a prince among them. They were led by the Constable of Suffolk, Hervey de Glanvill, who is so nondescript that we’re not even sure when he died, though he participated in some unrest in East Anglia in 1150 so it must have been some time after that. Townsfolk and farmers from all over Europe had assembled in Dover for the expedition, and each community sent its own captain. Those captains were similarly more or less lost to history sometime after their service at Lisbon. When they arrived in the city of Porto in mid-June, seeking some relief from the aforementioned rough weather, these Crusaders were approached by the local bishop, Pedro Pitões, who asked them to meet with King Alfonso of Portugal (d. 1185).

Alfonso had promoted himself from count of Portugal, vassal of the Kingdom of León, to king of an independent Portugal in 1139, following the fairly obscure Battle of Ourique. It took him until 1143 to convince his cousin, King Alfonso VII of León and Castile, to acknowledge his new status. His victory over Alfonso VII at the “Battle” (it was more like a very large, very important tournament) of Valdevez in either 1140 or 1141 helped make his case. But even as late as 1147 he was still working on convincing the Catholic Church that he was a king and not a count, and he figured that a big victory over the Muslims would nudge the pope over to his point of view, while also expanding his kingdom. He’d already defeated the Almoravid Empire at the city of Santarém in March but Lisbon was an even bigger prize.

Speaking of the Almoravids, on the Muslim side of the line the situation in Iberia was in a state of flux, to put it mildly. The Almoravid dynasty, which had ruled much of North Africa and al-Andalus for over a century, was ousted when the nascent Almohad Caliphate conquered Marrakesh in April 1147. The Almohads were the new power in North Africa, but it would be another decade before their hold over the former Almoravid territories there was secure and another decade beyond that before they firmly controlled al-Andalus. So the defenders of Lisbon were pretty much on their own. They were outnumbered, but not by much and only because the Crusaders—after Alfonso offered to: let them loot the city, let them collect ransom for their prisoners, give tracts of land to their leaders as fiefs, and exempt their traders from Portuguese commercial taxes—agreed to help capture the city.

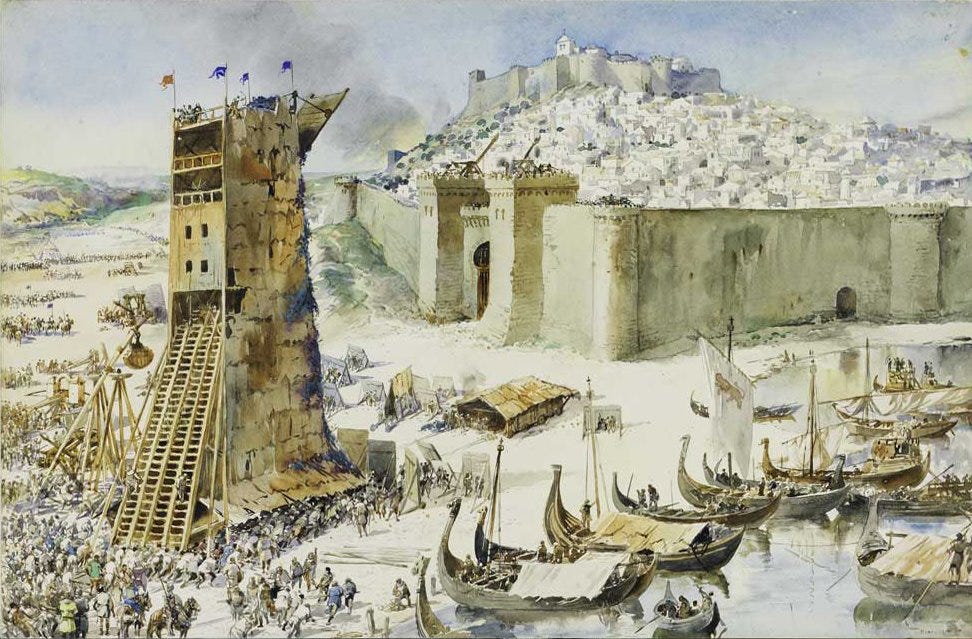

The siege began on July 1 and the Christians entered the by-then starving city victorious on October 25. It seems to have been relatively uneventful, though our modern understanding of these events is hampered somewhat by a lack of sources. Somebody, probably a priest in Hervey’s retinue, did write De expugnatione Lyxbonensi (“On the Conquest of Lisbon”), a Latin account of the siege, though as far as I know the author was more interested in conveying how grand and noble it was to be doing a Crusade than in recounting what actually happened. It does appear that the city surrendered on terms that its residents would be allowed to keep their lives and property, and that those terms were broken almost the instant the very loot-minded Crusaders got inside the walls.

In the wake of Lisbon’s conquest, many of the Crusaders chose to settle in the city while some others seem to have gone off to participate on other fronts of the Reconquista. Still others may have resumed their trip to the Holy Land but this is not well attested. And yet others, like Hervey de Glanvill, seem eventually to have made their way home. Lisbon, because of its favorable location compared with the northern city of Porto, became the capital of the Kingdom of Portugal in 1255 and has remained the Portuguese capital to the present day.