Today in European history: the Battle of Mohi (1241)

The Mongols conquer (albeit briefly) Hungary.

If you’re interested in history and foreign affairs, Foreign Exchanges is the newsletter for you! Sign up for free today for regular updates on international news and US foreign policy, delivered straight to your email inbox, or subscribe and unlock the full FX experience:

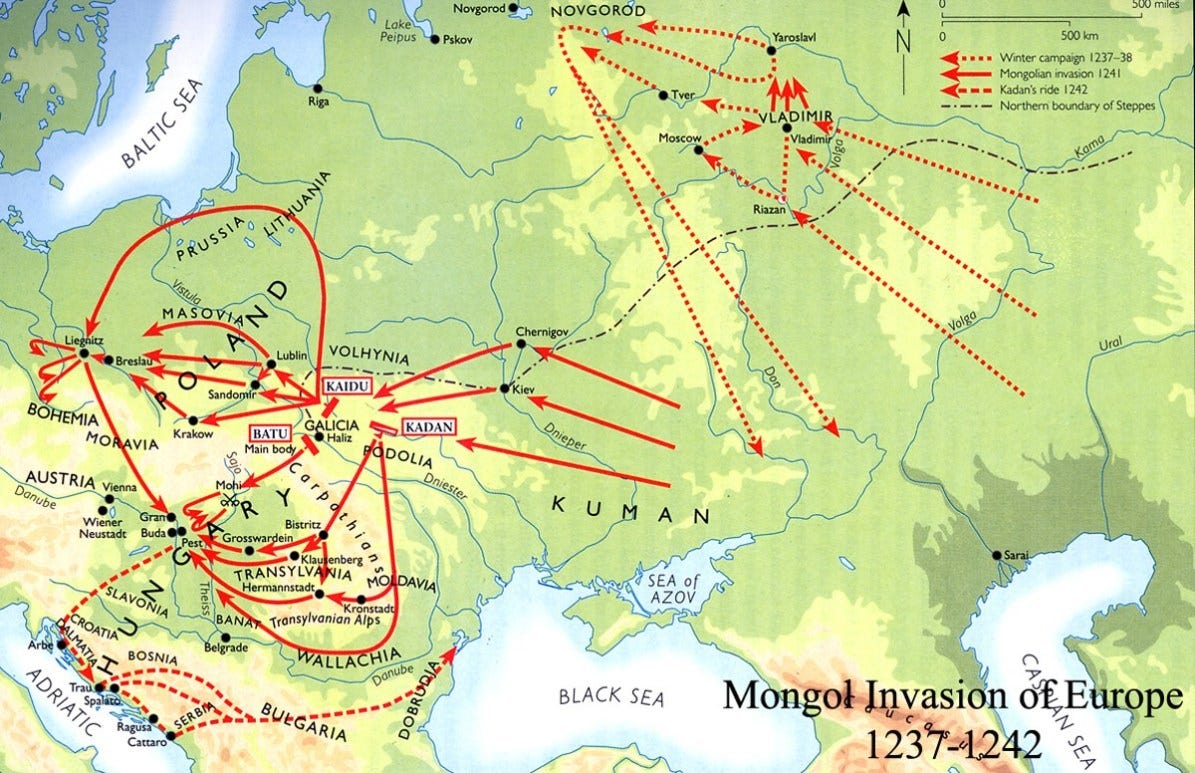

Having already talked about the Battle of Legnica a couple of days ago, we now turn to the Mongols’ other major April 1241 fight, the Battle of Mohi (also referred to as the Battle of the Sajó River) on April 11 (it technically may have begun on April 10, but close enough). If you’ve already read the story of Legnica then you know that this was a Mongol victory—one that arguably meant that, for a brief time at least, the Mongols had conquered Hungary. But their “conquest,” such as it was, lasted less than a year before their forces withdrew east and Hungarian King Béla IV (d. 1270) was able to regain (and begin to rebuild) his kingdom.

The Mongols invaded Hungary ostensibly in pursuit of the Cumans, a people that had once co-controlled, along with the Kipchaks, a khanate in the Eurasian steppe north of the Black and Caspian seas and stretching into Central Asia as we think of “Central Asia” today. The Cuman-Kipchak Confederation, as it’s often known, lasted for a bit over 300 years, from the 10th-13th centuries. They caused grief for the Byzantine Empire, Kievan Rus’, various Persian-speaking kingdoms in Central Asia, and pretty much anybody who happened to wander into their neck of the woods. One of the most important byproducts of the Cuman-Kipchak Confederation was the Mamluk Sultanate, which ruled Egypt and Syria from 1250 until 1517. That dynasty of slave soldiers and ex-slave rulers emerged (at least at first) from peoples who were born in the Kipchak steppe and were sold into slavery in Egypt by merchants operating in the Cuman-Kipchak Confederation.

Anyway, we don’t need to go into much detail about the Confederation because by this point it was pretty well kaput, destroyed by the Mongol expansion. The Cumans themselves fled west, where they joined an anti-Mongol alliance in the early 1220s but accepted a Mongolian bribe to abandon it. The Mongols then promptly attacked them anyway after they’d dispatched the rest of the alliance. The Cumans joined up with the Rus’ to face the Mongols at the Kalka River in 1223, where it’s said that their innovative tactical decision to run away before the battle got started was instrumental to the decisive Mongolian victory. They basically kept on fleeing all the way into Hungary, and the Mongols saw the Hungarians’ decision to shelter them as a cause—or, maybe, a convenient justification—to invade.

The Mongol invasion of Hungary was jointly commanded by a Mongolian prince named Batu (d. 1255), who was considered Genghis Khan’s grandson despite questions about his ancestry, and Subutai (d. 1248), whose career as a general stacks up to just about anyone’s in history. The Mongols often did a joint command thing where a young royal would be sent out alongside a seasoned general, with the general in actual command and the royal there more to gain experience. Such was the case here.

They were opposed by an army commanded by the aforementioned Béla IV. This was supposed to be a Hungarian-Cuman army, but things didn’t quite work out that way. The Hungarian people were not too keen on the Cumans, apparently, and particularly resented the favoritism that their relatively new (he took the throne in 1235) king showed them. With a Mongol invasion seeming imminent and the Cumans looking like the cause of it, in 1239 some Hungarian noble arranged the murder of the Cuman khan, Köten, in the city of Pest. After this the Cumans decided to split and headed south, pillaging the Hungarian countryside as they went in vengeance for their dead khan. So they were out of the picture. Frederick II, Duke of Austria (d. 1246), brought an army to Béla’s aid at Pest, but that proved to be kind of a mixed blessing as we’ll see in a moment.

Here’s what happened: the Mongols sent a detachment of men toward Pest to do some raiding, hoping to draw Béla and his army out of the city to give chase. Béla didn’t fall for this, at first, but his better instincts were overridden by concerns over, well, perceptions about his manliness, to be frank. While Béla and his army holed up in the city, Frederick led his men out to victory against a small Mongolian raiding party, then (kind of hilariously, in retrospect) declared victory and went back to Austria. As Frederick had some claims on Hungarian territory in the west, the Hungarian king felt he had no choice but to sally forth from the city and fight the Mongols in the open field, lest he be seen as a coward in comparison with his Austrian rival.

This proved to be a catastrophic mistake, because the Mongols had other ideas. Instead of standing toe-to-toe with the Hungarian army, they opted to go back to their favorite tactic, the feigned retreat. They were hoping to sucker the Hungarians into chasing them, and Béla—compounding his initial mistake—obliged. He chased them all the way to the River Sajó, in face, where the main Mongol army was encamped. Now, here’s the part where I give you the usual futile attempt at estimating numbers, which is harder than usual in this case because the estimates are all over the map. Most sources put the Mongols somewhere in the 20,000-30,000 range but there are a few that go higher. Some sources put the Hungarians as low as 15,000 men but others say the Hungarians outnumbered the Mongols. I’m going to say these were probably similar-sized armies with the Mongols possibly even having a small edge in numbers.

Béla now got cautious again, and decided to set up a fortification along the western bank of the river instead of crossing over to continue the chase. This decision had mixed results. The Mongols wanted the Hungarians to cross the river and were likely planning to attack them as they did, which could have been a bloodbath. But instead, Béla’s decision locked his army in place and allowed the Mongols to dictate the movements and terms of the ensuing battle. The result was, well, a bloodbath. Subutai made the decision to divide his forces, leaving most of the army under Batu to try to cross the Sajó Bridge and attack the Hungarians head-on, while he took a detachment downstream to cross the river covertly and surprise them. It worked, albeit at fairly considerable cost to Batu’s men.

The Hungarians struck first by taking control of the Sajó Bridge on the night of April 10, before the Mongols could cross it. This forced Batu to divide his forces again, sending a small group upstream to cross the river and come up behind the Hungarians defending the bridge. At dawn, the Mongols attacked and were eventually able to take the bridge and begin their assault on the main Hungarian fortification. The Hungarians seem to have been completely blindsided by this, and this could be because they still thought they were facing the small Mongol raiding party they’d chased away from Pest and didn’t yet understand that they’d been led into a trap. But they were able to inflict heavy losses on Batu’s army, until Subutai finally arrived and drove the Hungarians back into their makeshift fort.

This is where the decision to build the fort really turned out to be a mistake. If the rattled Hungarians had just retreated at this point, they probably could’ve gotten back to Pest with their army mostly intact. The Mongols were spent and Subutai hadn’t been able to surround the Hungarian army as he’d planned upon arrival. But because they’d just built this new nice defensive fortification, they holed up in preparation for a Mongolian attack. They had no supplies to withstand a siege, though, so the Mongols simply shifted gears and decided to wait the Hungarians out. After a few hours and a few failed attempts to break the Mongol siege, the desperate Hungarians finally decided to run after all. Luckily, they found a gap in the Mongol line right where they needed it to be. What a break!

You’ve probably already figured out where this is going. Of course that gap in the line wasn’t lucky at all. The Mongols, who’d now had the time to properly encircle the Hungarian position and plan their next moves, left it there hoping to trick the Hungarians into fleeing through it. When the Hungarians politely obliged, Mongolian horse archers rode them down and slaughtered them almost at will. Béla somehow managed to get away, but the vast majority of his army wasn’t so fortunate.

The engagement at Mohi is interesting, I think, because it illustrates a couple of things about the Mongols. First, I would argue that it shows that, when they weren’t able to force a fight on their own terms, the Mongols could be vulnerable. Batu’s army seems to have taken a heck of a beating, bad enough that he was purportedly ready to retreat for real until Subutai showed up. Second, it shows that even when the Mongols were vulnerable they were still, especially under the command of someone like Subutai, a military juggernaut, capable of adapting quickly and exploiting potential enemy mistakes.

Mohi was as decisive an inconsequential battle as you’ll ever see. Decisive because, afterward, the Mongols were for a time the unchallenged rulers of Hungary. They occupied virtually the entire country, captured and razed the city of Pest, killed maybe a quarter of the population, and drove most of the rest into the hills and other relatively inaccessible areas. Béla appealed to Pope Gregory IX (d. August 1241) for help. Gregory called for a crusade against the Mongols and…was met with the sound of crickets, thanks to his long-running feud with the Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II (d. 1250, and not to be confused with Duke Frederick II from earlier in our story). Luckily for Béla, as it turns out the Mongols weren’t sticking around. In early 1242, they withdrew from Hungary, which is why this battle was ultimately inconsequential.

As I mentioned in discussing Legnica, the Great Khan Ögedei died in 1241, and as a royal Batu had to take much of his army east to make sure he didn’t get screwed in the upcoming succession process. He didn’t go all the way back to Mongolia, but he did park himself and his army at the Volga River with the intention of defending what he saw as his dominion against any Mongolian reorganization plans. That may be part of the reason for the withdrawal.

However, there are other reason to think the Mongols had hit at least the temporary end of the line as far as their invasion was concerned. The Mongol position in Hungary was vulnerable for several reasons, including the losses they’d taken during the campaign and the lack of enough adequate pastureland to accommodate a large occupying army and all of its horses (Mongolian armies usually took at least 3 horses for every rider). Furthermore, the Mongols always liked to know something about where they were going before they got there and it’s likely they’d reached the extent of their knowledge with respect to central Europe. And they were only just starting to encounter heavy European-style fortifications, which necessitated an adjustment in siege tactics. All of these things would have argued for a retreat and regrouping no matter what happened back east. It’s also possible that the Batu-Subutai expedition had never intended to permanently occupy Hungary, but merely to weaken it for a future conquest. In that case, the Mongol withdrawal would have been planned and only subsequent events prevented the grand strategy from being implemented.

Whatever the reasons for this withdrawal, the Mongols wouldn’t be back for decades. Intra-dynastic rivalries, at times escalating to civil war, weakened Mongolian cohesion and put expansion plans on hold for a while. During that time, Béla reasserted control over his kingdom and went on a castle-building spree. He likely reasoned that he would be unable to beat an invading Mongol army in the open field, but that he could starve it by hoarding the country’s food in heavily fortified castles and force it to waste time besieging those castles. And he was right, though he didn’t live to see it. The second Mongolian attempt to invade Hungary didn’t happen until 1285, and it failed miserably, in part because the Mongols were unable to feed themselves and unable to capture any of those castles.