Today in European history: the Battle of Preveza (1538)

The Ottoman navy wins a significant, if anticlimactic, victory over the 1538 Holy League off the coast of Greece.

If you’re interested in history and foreign affairs, Foreign Exchanges is the newsletter for you! Sign up for free today for regular updates on international news and US foreign policy, delivered straight to your email inbox, or subscribe and unlock the full FX experience:

There are a couple of anniversaries we could commemorate today. For example, if you’re a fan of lost causes, on this date in 1995 Yitzhak Rabin and Yasser Arafat signed the Oslo II accord, which was supposed to provide for Palestinian autonomy leading to future (HA!) talks on an independent Palestinian state. Five years later (in 2000), then-Israeli Defense Minister Ariel Sharon did his part to bury Oslo II as deep as he possibly could by “visiting” the Al-Aqsa/Temple Mount area and precipitating the Second Intifada. If the lives and times of Arab strongmen are more your thing, then you probably already know that Egyptian President Gamal Abdel Nasser died on this date in 1970, which sent shockwaves across the Arab world and realigned regional geopolitics in several ways.

But we’re going to ignore those more recent events and go back to 1538 to talk about the (naval) Battle of Preveza, which was the decisive battle in the third of seven Ottoman-Venetian wars (most of which didn’t go well for the Venetians) that took place between the 15th and 18th centuries. This war ran from 1537 to 1540 and initially involved a joint invasion of Habsburg Italy by the Ottomans (from the south) and their new French allies (from the north). The French invasion stalled out, though, and the Ottomans withdrew their forces from Italy but continued the war nevertheless.

Venice was never much of a land power, but it was one of the naval giants of the Mediterranean for quite a long time. It was inevitable that, as the Ottomans began to build up their naval strength in the mid-1400s, they would butt heads with the Venetians, who saw their domination of Mediterranean shipping lanes in almost existential terms. And they did butt heads, in 1463-1479 (when the Ottomans captured the large Greek island of Euboea and most of the Morea, or the Peloponnese region of Greece) and again in 1499-1503 (when the Ottomans consolidated their control over the Morea).

In 1537, the commander of the Ottoman navy (Kapudan-i Derya, or “Captain of the Sea,” also called the Kapudan Pasha), the famous/infamous Hayreddin Barbarossa (d. 1546), captured several Greek islands that had previously been under Venetian control, and the two naval powers headed for a third war. Venice appealed to Pope Paul III (d. 1549), who quickly formed a Holy League composed of Venice, Habsburg Spain, the Papal States, Genoa, and the Knights Hospitaller from Malta, all under the command of Habsburg Emperor Charles V’s best naval commander, the Genoese admiral Andrea Doria (d. 1560). By 1538 they were ready to put an end to the Ottomans’ naval expansion. Or, at least, they must have assumed they were.

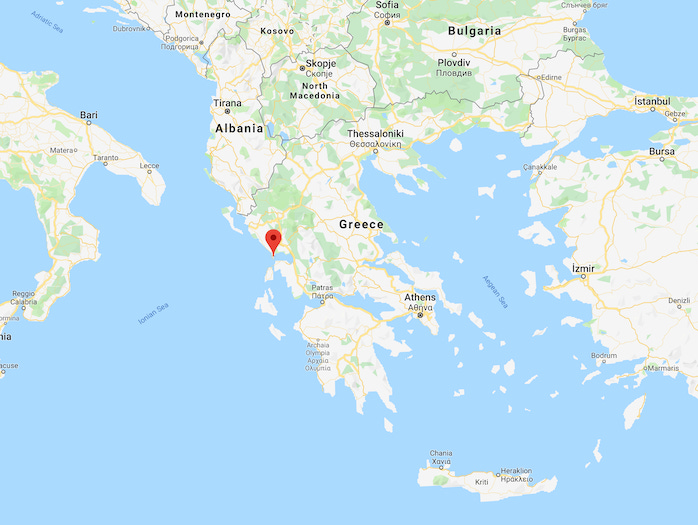

Preveza is located on the west coast of Greece. At the time it was an Ottoman port and was heavily coveted by the Venetians. They did eventually take it from the Ottomans, but not until the 18th century. Uh, spoiler alert I guess.

That’s a pretty strategic location for an Ottoman Empire that wants to project naval strength to the west and for a Venetian Republic that would like to be able to sail its ships through the Adriatic and into the Mediterranean without being harassed. Moreover, the Ottomans always had their eye on the Ionian island of Corfu (just north and a bit west of Preveza). For the Ottomans, Corfu was strategically located both from a naval perspective and from a “we might like to invade Italy again some day” perspective. To wit, the Ottomans had tried and failed to take Corfu in a siege the previous August. If they lost Preveza, their chances of mounting another attempt to take Corfu would be minimal at best.

The Ottoman fleet was outmanned and outgunned, as it had fewer ships than the Holy League and some of its ships were galliots (also known as “half galleys”) while the major Christian ships were full galleys and even some larger galleons—Venice was the first naval power to experiment with the larger, sail-powered ship class that ultimately came to dominate naval warfare. The Christians also had a whole lot of smaller barques. Barbarossa had a well-deserved reputation as a great naval warrior (Charles supposedly tried to bribe him to switch allegiances at one point, only to have Barbarossa decapitate the man sent to make the offer), but Andrea Doria was no slouch either, having become famous as the commander of the once-mighty Genoese navy (we’ll revisit this point shortly).

One of the keys of Preveza’s naval engagement turned out, ironically, to be control of the land around the area where the battle was fought. The Holy League attempted to capture Preveza’s fortress but was unsuccessful. Barbarossa, meanwhile, put troops ashore at Actium, which is better known to fans of Roman history as the site of Marc Antony’s crushing defeat at the hands of Octavian and Agrippa in 31 BCE. Actium also happens to be very close (“within cannon range” close) to Preveza. After their Preveza setback, the Christians weren’t willing to risk another landing to dislodge the Ottomans from Actium, but this meant that the Christian fleet had to avoid getting within range of Ottoman shore guns, and since the wind could inadvertently blow the Christian ships toward the coast, this meant that they had to anchor near the island of Lefkada to the south.

Andrea Doria figured that Barbarossa wouldn’t give up his favorable spot near Actium to chase the larger Christian fleet south. So he must have been surprised when, as he was working on a plan to draw Barbarossa out on the morning of September 28, he was informed that, no, Barbarossa had chased him south. Not only was Doria caught off guard, he was also handcuffed by the lack of wind, which made it hard for the smaller-sailed Christian barques to move around and thus left them at the mercy of the Ottoman ships. Doria tried to get the Ottomans to engage with his larger ships out at sea, but Barbarossa mostly refused to take the bait. The Ottomans sank several Christian ships and captured many more, and didn’t lose a single vessel (although several Ottoman galleys that had taken the bait and and attacked the Venetian flagship, a galleon, were badly damaged).

Now here’s where things take a peculiar turn. The next morning, when the winds allowed, Andrea Doria took his fleet and…fled. There’s no obvious explanation for this decision. The Christian fleet had taken some losses, yes, but it still outnumbered the Ottomans and still had a big advantage in its larger, sturdier, more heavily armed ships (most of which, apart from that one Venetian galleon, hadn’t really gotten into the fight the day before). Virtually everybody else in the fleet (the Venetians, the Papal fleet, the Knights Hospitaller) wanted to stay and fight. But Andrea Doria wouldn’t hear of it, and if he and the Spanish and Genoese ships were leaving, the remaining fleet would lose its commander and its numbers edge and pretty much had to go too. So the battle came to a relatively anticlimactic end.

Why did Andrea Doria check out so quickly? Well, I think we can identify two reasons. First, he wasn’t just the commander of the Habsburg and Genoese fleets—because of the way navies were organized back then, he actually owned a lot of their ships. He was fine sending Venetian and Maltese vessels out to get bombarded, but he doesn’t seem to have been as willing to risk his own property in the fight. That’s probably got something to do with our second reason, which is that Andrea Doria kind of hated the Venetians. Venice and Genoa were rivals for Mediterranean supremacy through the 1400s, until Genoa finally lost their contest, and its autonomy to boot, and became a satellite of the Habsburg Empire. In hindsight, he was probably the wrong choice to command a fleet that was assembled to protect Venetian commercial interests in the eastern Mediterranean, since he personally couldn’t have cared less about Venice or its commerce. I’ve even seen suggestions that Andrea Doria had arranged his sudden retreat with Barbarossa before the battle, but I don’t think there’s hard evidence to support that theory.

With the Holy League’s fleet off the board, there was little that Venice could do to regain the initiative. The Ottoman victory at the Siege of Castelnuovo (modern day Herceg Novi, in Montenegro), brought the war to a decisive end. When it was over, the Ottomans had taken most of Venice’s remaining holdings in the Greek islands and its last settlements in the Morea. One thing that eluded the Ottomans, however, was Corfu. That island was so well-fortified that the Ottomans were never able to capture it, and it only fell out of Venetian control during the Napoleonic period, when it went first to France and then to Britain, which in turn bequeathed it to Greece along with the other Ionian islands in 1864.