Today in European history: the Battle of Legnica (1241)

A small Mongolian army under the command of Orda, one of Genghis Khan’s grandsons, defeats a Polish force under the command of Grand Duke Henry II.

If you’re interested in history and foreign affairs, Foreign Exchanges is the newsletter for you! Sign up for free today for regular updates on international news and US foreign policy, delivered straight to your email inbox, or subscribe and unlock the full FX experience:

The double-envelopment, or pincer movement, is such a tried and true military tactic that the guy who literally wrote the book on war, Sun Tzu, discussed it in his book. It involves, as the name suggests, outflanking an enemy on both sides in order to encircle it completely. Sun Tzu actually argued against employing this tactic, because if carried through to completion it leaves the enemy no opportunity to retreat, and he believed that it was better to give your enemy a chance to flee than to force it to fight with its back against the proverbial wall.

That’s not bad reasoning, but with all due respect to Sun Tzu we should note that some of history’s greatest massacres have been visited upon armies that were completely enveloped by their enemies. There are challenges with attempting this kind of tactic, including complexity and the vulnerability of your army’s center, which has to engage the enemy and hold out long enough for the flanks do all their flanking maneuvers, but in several major engagements in which it’s been successfully implemented—Hannibal at Cannae in 216 BCE, the Seljuks at Manzikert in 1071, Daniel Morgan at Cowpens in 1781—the army using the pincer has won with heavy casualties on the other side (the Romans lost well over 50,000 men at Cannae, for example, which seems like a lot nowadays but was massive for a battle in ancient times).

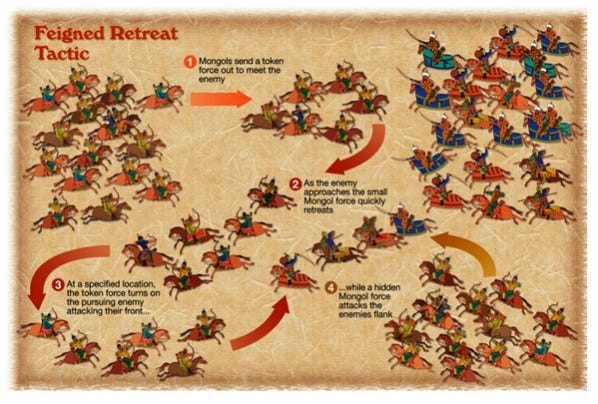

It’s likely that no army has ever made more use (or at least more famous use) of the pincer movement than the Mongolian army, or I guess the several Mongolian armies because there were usually many of them out campaigning at any one time. They used a variant of the pincer movement that (Sun Tzu would approve) generally didn’t envelop the enemy from the rear and thus left them a way out if they could get back the way they’d come. They also, usually, didn’t anchor the fighting with the center of their line while their flanks maneuvered around the enemy position. Instead, the Mongol forces, primarily made up of highly maneuverable mounted archers, would “retreat” at the center in order to get the enemy army, or at least part of it, to chase them and basically envelop itself. This is an incredibly difficult tactic to pull off, mostly because a feigned retreat—which has to look like a chaotic flight to pull off the deception—can turn very easily into a real retreat if you’re not careful. But the Mongols were experts at it.

I note the Battle of Legnica’s anniversary today not because it was a huge or even particularly important battle, but because it gives me a chance to write all that stuff about feigned retreats and pincer movements. Legnica (or Liegnitz for you German speakers out there) was the culmination of the first Mongol “invasion” of Poland, which was less an invasion than it was a diversionary raid. There was a large Mongolian invasion of Europe happening at the time, but it was centered on Hungary, which had recently welcomed a large number of Turkic Cumans who were sick of being defeated by the Mongols in Central Asia and Eastern Europe.

Two large Mongolian armies, one under Genghis Khan’s grandson Batu (d. 1255) and the other under the legendary Mongolian general Subutai (d. 1248), chased the Cumans into Hungary in late-1240/early-1241, while a third, considerably smaller army under another of Genghis Khan’s grandsons, Orda (d. 1251), raided Poland. This third force probably numbered less than 10,000 at the start of its campaign, and would have been smaller than that by the time of Legnica due to casualties suffered along the way.

In late March 1241, Orda learned that the High Duke of Poland, Henry II (d. 1241, spoiler alert), had gathered an army at Legnica and was waiting for the arrival of a second, much larger force, under the command of Wenceslaus I of Bohemia (d. 1253). Orda decided to strike Henry before the two armies could link up, at which point they would’ve vastly outnumbered the Mongols. The rest of the story you should already have figured out by now. The Mongols engaged Henry’s army, feigned a retreat, Henry chased them, and they closed the trap. Nearly Henry’s entire army seems to have been killed, including Henry himself (he was apparently captured and beheaded, which is curiously mundane considering the inventive ways we’re told that the Mongols usually executed captured royal enemies).

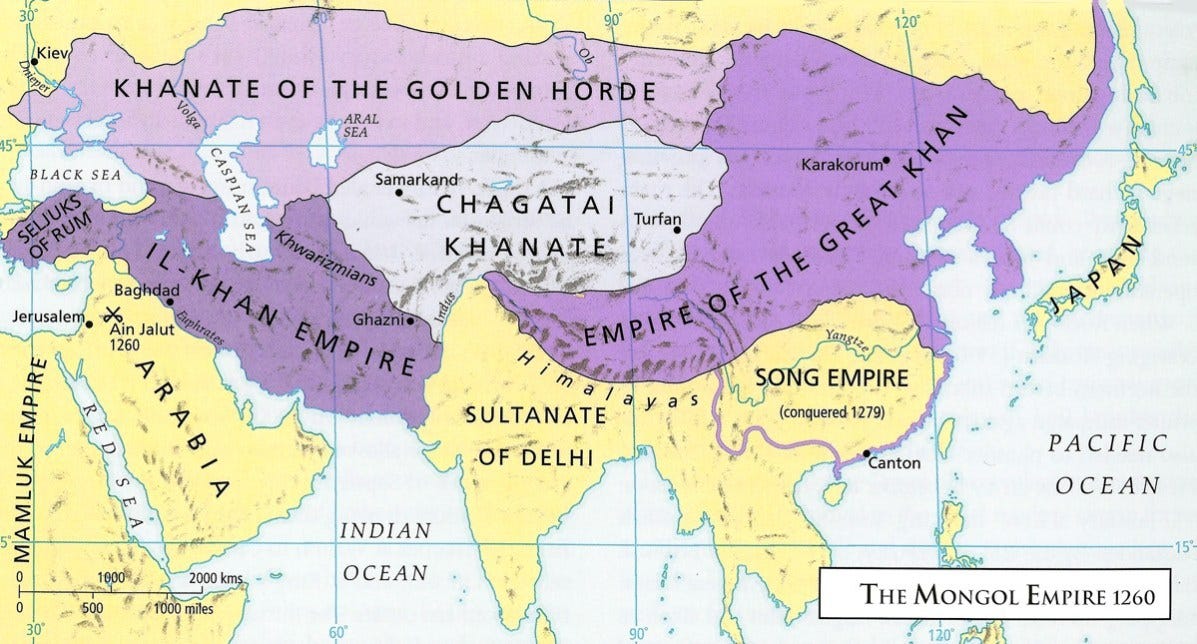

Orda, still concerned about facing a Bohemian army that on its own outnumbered his small force, opted to leave Poland after the battle. He headed south to join Batu and Subutai, and by the time he met up with them they’d already defeated the Hungarian army at Mohi on April 11. Despite this string of victories, Legnica and Mohi marked the end of this particular Mongol incursion into Europe. The Great Khan, Ögedei, died in 1241, and Batu took a significant part of his army back east in order to participate in the succession process and make sure his interests were protected. Because of Mongolian dynastic politics, which we have no reason to talk about here, he didn’t return west for over a decade, at which point “the Mongol Empire” was really four separate empires with only nominal allegiance to a single Great Khan in the east. Batu and his family, who were descendants of Genghis Khan’s eldest son (well, it’s debatable whether he actually was Genghis Khan’s biological son, but whatever) Jochi, ruled the “Golden Horde” Khanate, shown below:

The Mongols were also, in hindsight, reaching their geographical limits. Batu’s 1240-1241 invasion of Europe stalled because Batu had to return east for the succession, but his army was running out of able-bodied soldiers, was starting to see revolts break out in parts of Eastern Europe that it had previously conquered, and was without adequate pasture for its massive herd of horses in the central European climate. On top of that, eastern and central European rulers began to adopt a different approach to Mongol invasions: withdrawing, along with most of their food and other supplies, into their many castles. The Mongols were capable at siege warfare but it could be time consuming, and the lack of readily available supplies made it difficult to sustain a lengthy siege. We don’t know how far Batu planned on going during this invasion, but it seems clear that his withdrawal in 1241 helped keep a decent sized chunk of Europe out of Mongolian hands.