GUEST POST: Bed, Ba’ath, and Beyond, part 1

Saddam’s Shopping Extravaganza

Hello readers! Today I’m very pleased to bring you the second Foreign Exchanges guest post! Arms proliferation researcher Travis Haycraft joins us for the first part of a two-parter (coming next month) on Iraq. Part one looks at the Saddam Hussein-organized build up of the Iraqi military in the 1970s, leading up to the Iran-Iraq War. It’s a story of weapons, money, oil, and all the friends Saddam made along the way.

As always, if you would like to pitch something for Foreign Exchanges, please email me. And if you’ve enjoyed this piece or any of our guest pieces, please subscribe to support more guest writers and to unlock the full Foreign Exchanges experience:

by Travis Haycraft

What do you do when you want to turn your poor, underdeveloped post-colonial state, embroiled in ethnic and political strife, into a respected world power? Do you engage in careful democratic reform, infrastructure development, and popular welfare programs? Or do you ride a tank through the gates of the presidential palace and spend the next twenty years treating the world’s arms companies like an all-you-can-eat buffet?

When Saddam Hussein rode a tank through the gates of the Iraqi Presidential Palace in 1968 and began his rise to the top, Iraq was just such a state. The former British possession had only a small military that was incapable of dealing with unruly Kurdish separatists, let alone reaching the heights Saddam envisioned for it.

What Saddam didn’t lack was ambition. He wanted to humiliate Israel, make Iraq the leader of the Arab world, and weaken Iraq’s then-chief rival, Iran. His ambitions came to fruition in the form of a shopping spree of epic proportions around the world, in order to build the military that would, in 1980, lead the charge across the Iranian border.

Iraq had a long way to go before it was capable of taking on a country as large and rich as Iran, itself the darling of the United States and the number one customer for American weapons. The Iranians had an army a half-million strong to go with the latest in American technology. The Ba’athists had struggled to regain their footing in Iraqi politics after the November 1963 shakeup that drove them out of Abdul Salam Arif’s government. But the 1968 coup brought the party back into power and established Saddam as the number two man in Iraq behind his cousin, Ahmed Hassan al-Bakr.

This new government inherited a weak military, as at the time Iraq had a mere 92,000 troops in its military and spent just $250 million on defense annually. Iraq had just a single armored division, with fewer than five hundred tanks—mostly older Soviet models such as the T-34, T-54, and T-55. Those tanks were supplemented by fewer than one hundred armored personnel carriers. The air force had been built almost entirely after the 1958 military coup that switched Iraq’s military patron from the United Kingdom to the Soviet Union, and as a result consisted mostly of older Soviet jet fighters such as the MiG-21 and Su-7. Furthermore, almost all of Iraq’s military relied on Soviet assistance and training, even for basic equipment maintenance. The Soviets had refused to give the Iraqis any independence in terms of maintaining the weapons they bought, even requiring that engines in need of repair be sent back to the Soviet Union.

Since its independence from Britain, Iraq had been embroiled in a crippling conflict against Kurdish separatists in the north of the country who were supported by the Iranian Pahlavi monarchy, which wielded its oil wealth and political influence to purchase vast quantities of arms from the United States and United Kingdom and which passed along much of its vast arsenal to the Kurdish militias. Iraq’s suppression of the Kurdish rebellion in 1969 and 1970 was incredibly brutal, and the Soviets started to worry about a potential PR disaster. In order to get ahead of any accusations that they were aiding human rights abuses, the Soviets withdrew their military support to Iraq, crippling the Iraqi military and forcing Saddam to sign a four-year ceasefire with the Kurds.

Furthermore, the Arab defeat in the 1973 Arab-Israeli war proved to Saddam that reliance on Soviet-made weapons was unsustainable not only because it gave Moscow too much power over Iraq, but also because the weapons the Soviets were willing to sell were simply inferior to Western arms. The Arab armies, equipped entirely with Soviet technology, had been soundly beaten by Israeli forces armed with American and French technology. If the Iraqi military were to reach the heights Saddam envisioned for it, Iraq had to look to the West for its weapons.

Saddam believed that the best place to start was France. Although Iraq had a poorly equipped military and little in the way of industry, it did have vast amounts of oil. As Bakr’s second-in command, Saddam used every lever at his disposal to consolidate his own power. He assumed control over much of Iraq’s oil industry in 1972 and decided to leverage those resources to rebuild the Iraqi military—which would then, presumably, be loyal to him. Saddam made his first pilgrimage to Paris in 1972, meeting French President Georges Pompidou. He made a small purchase of a few Alouette helicopters and Panhard armored cars—nothing that would change the balance of power against either the Kurdish militias or Iran, but enough to whet both the Iraqi and French appetites for each other’s goods. This first meeting with the French seemed to indicate to Saddam that his ambitions could be realized, with the proper application of money.

In March of 1975, French experts from Avions Marcel Dassault-Bréguet Aviation, the manufacturer of the coveted Mirage fighter jet; Snecma, the manufacturer of the Mirage’s jet engine; and the Government export agency Office Générale de l’Aire arrived in Baghdad and joined with diplomats from the French embassy. The French team told the Iraqis they could indeed sell them the Mirage 3 jet that the Israelis had famously used to great success in 1973 and, in fact, could do better. Dassault had recently released a newer, better fighter jet called the Mirage F1 that was categorically superior to the Mirage 3. More importantly than the jets, however, France was offering the technology and skills to maintain and repair the weapons they sold to Iraq—something the Soviets had never done.

While French agents were working on the Mirage deal in Baghdad, Saddam flew to Paris to meet new French Prime Minister Jacques Chirac to request a massive, immediate arms delivery to aid in Iraq’s suppression of yet another Kurdish rebellion. Chirac refused the immediate request but did agree to future sales. Saddam secured contracts to purchase dozens of weapons systems and technologies, including Exocet anti-ship missiles, Milan and HOT anti-tank missiles, Martel and ARMAT anti-radar missiles, Magic air-to-air missiles, Alouette, Gazelle, and Super-Puma helicopters, self-propelled howitzers, radars, military electronics, and much more. Chirac even agreed to help construct a nuclear reactor complex in western Iraq to be called Tammuz I/II and agreed to train Iraqis in the maintenance, repair, and manufacture of many of the weapons they would be receiving.

In June 1977, the Mirage fighter jet sale was finalized, and Iraq bought thirty-six aircraft for $1.8 billion. Also included in the deal were 110 AMX-10P light tanks, anti-tank guided missiles, and fourteen Super Frelon helicopters designed to launch Exocet anti-ship missiles. France also agreed not only to maintain and repair Soviet-made equipment but also to train Iraqis to do it themselves.

While these weapons would not start arriving en masse for several years, Iraq’s shift away from Soviet dependency and willingness to buy from new countries was key to Saddam’s armament plan.

The flow of foreign experts into Iraq increased exponentially. Other developing countries were beginning to offer arms on the international market, often at far lower prices than their superpower competitors. Yugoslavia, Egypt, China, and Brazil began receiving Iraqi oil and cash in exchange for weapons. Brazil in particular was vital in developing Iraq’s military industrial complex. The Brazilian manufacturing company Engesa began selling weapons to Iraq in 1976 with a huge $836 million deal that included 150 Cascavel armored cars, 150 Urutu Scout Cars, and 2000 other trucks. Brazilian scientists and engineers soon became ubiquitous in Iraq.

As billions of dollars of Iraqi money began flowing to France, Brazil, and elsewhere, the Soviet Union quickly realized that not only was Saddam no longer beholden to Soviet interests but also that the Soviet Union was losing the opportunity to get their hands on Iraqi cash, which was now flowing freely. The allure of Iraq’s money was too great for the Soviets to ignore. Thus, in 1976, Soviet envoys in Baghdad ended their arms embargo and signed a multi-billion dollar deal for the MiG-23 fighter jet, the most modern the Soviets had to offer, as well as missiles, artillery, tanks, and, most importantly, the training of Iraqi pilots and mechanics.

The 1976 deal made it clear that Iraq’s former dependence on the Soviets was long gone. The new diversity of Iraq’s vendors and Baghdad’s willingness to spend freely meant that the Iraqis could take the upper hand in negotiations with the Soviets. In 1978, they signed a $3 billion arms deal, the largest to that point in Iraqi history, which included 138 MiG-23 fighters, SCUD-B ballistic missiles, Il-76 transport planes, Mi-8 transport helicopters, SA-7 anti-aircraft missile systems, MiG-25 reconnaissance jets, and more. Despite this substantial deal, the Soviet share of Iraqi arms purchases had dropped from 95 percent at the beginning of the 1970s down to 63 percent by 1979.

Saddam also managed to score a small number of civilian helicopters from the American Bell helicopter manufacturer, as well as ship engines from General Electric—another American company—intended to power Italian-made frigates for the navy Saddam was planning to build. These sales were initially blocked by the State Department, but pressure from President Carter’s administration greased the wheels, allowing the sales to eventually go through.

Iraqi defense expenditures increased from $734 million in 1972 to $5.1 billion in 1979. Iraqi arms vendors came to include Brazil, China, Czechoslovakia, East Germany, West Germany, Egypt, France, the United Kingdom, Hungary, Italy, Jordan, Libya, Poland, Romania, Spain, Switzerland, and the United States. And by 1980, though much of Iraq’s equipment—such as the T-54/55 tanks and MiG-21 jets—remained older Soviet equipment from the 1950s and 1960s, billions of dollars of new equipment was either in place or on order.

In addition, Iraq had nineteen state-run ordnance factories that produced, under license, a wide variety of small arms, heavy weapons, and ammunition. While none of these weapons systems were particularly complex or advanced, they formed the backbone of the Iraqi military, granting Iraq a degree of logistical independence it had never had before.

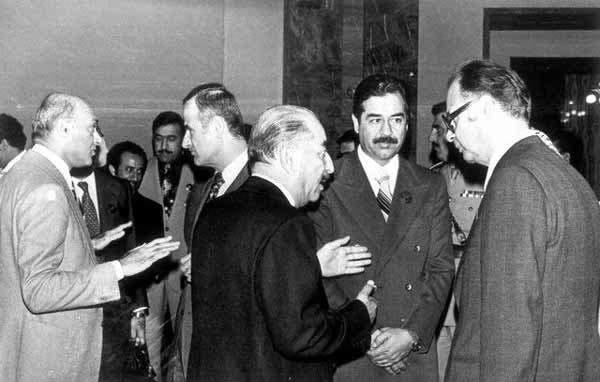

Saddam Hussein (second from right) at a 1978 Arab Summit in Baghdad (Wikimedia Commons)

It was this independence that gave Saddam and his cadre the false bravado to begin planning a war with Iran in the chaos following the 1979 Islamic Revolution, which paralyzed the Iranian military. Saddam, who forced out Bakr and assumed the Iraqi presidency himself that same year, ordered his military leadership to put together a war plan. Iraqi forces would advance a short distance into Iran—10 or 20 kilometers—forcing Iran to counter with their Revolutionary Militia forces stationed around distant Tehran. This would leave Tehran exposed, allowing for a counter-revolution under Iraqi guidance to take power. In the ensuing chaos, Iraq could seize the oil-rich province of Khuzestan, which lay along Iraq’s southern border. The war was expected to last no more than eight weeks. Thus, ten years after Saddam Hussein set out to rebuild the Iraqi military and with tensions between the two countries at an all-time high, Iraq invaded Iran on September 22, 1980.

(To be continued…)

Travis Haycraft graduated from the College of William & Mary with a degree in Middle Eastern Studies. His research interests include arms proliferation in the Middle East, with a particular focus on tanks and tank warfare. Travis is originally from New Orleans and currently works in Erbil, Iraq.