GUEST POST: Australia, Indonesia, and East Timor

I’m very happy to have another guest piece to bring you all today. In this outing, Pat Honan walks us through the Timorese independence movement, from its origins under Portuguese colonialism to the struggle for freedom from Indonesia’s exploitative and often brutal ethnic cleansing campaign, with a special focus on the Australian government’s efforts to steer events in Timor-Leste to its own benefit.

Hosting guest writers is one of the things I hope to continue doing, and with increasing frequency, here at FX. If you would like to pitch something of your own for Foreign Exchanges, contact me at fx.submissions@gmail.com or just click the button:

And if you enjoy these guest posts, which are always free to the public, please support them with a subscription today:

by Pat Honan

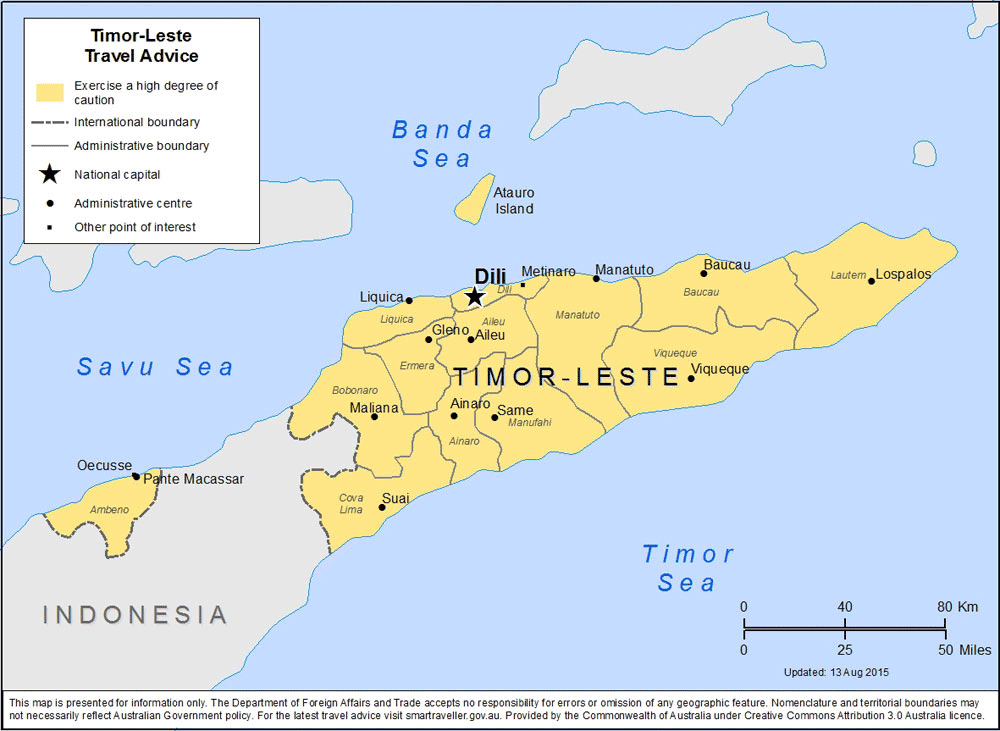

Timor-Leste (aka “East Timor”) is a small country that covers half of the island of Timor. It is located 400 kilometres from Darwin, Australia’s northernmost capital city, and was a former Portuguese colony. A small country in Southeast Asia, Timor-Leste has had fraught and exploitative relationships with its parent nation Portugal as well as its immediate neighbours, Indonesia and Australia, and is in many ways a bold example of the failures of colonialism. This article will deal specifically with the post-Portuguese colonial period of Timorese history.

(Source)

The move towards Timorese independence was triggered by the 1974 Carnation Revolution in Portugal, rather than any successful pressure campaign from within Timor-Leste. Portugal’s colonies were an enormous drain on the national budget and the National Salvation Junta, which governed Portugal after the revolution, needed cash fast. So Portuguese armed forces and colonial bureaucrats were recalled to the homeland and the colonies were effectively abandoned. This caused civil war in Angola and Mozambique and left Timor-Leste in a precarious position. Unlike those African colonies, Timor-Leste was entirely surrounded by a relatively new regional power in Indonesia, which had won its own colonial independence 30 years previously through a deft and ingenious use of Japanese aggression to chase the colonial Dutch out of the archipelago.

Following the Portuguese withdrawal there was an attempt made at forming a unity government between the two major Timorese political parties, the Frente Revolucionária de Timor-Leste Independente (FRETILIN), a left wing revolutionary party, and the União Democrática Timorense (UDT), a right wing independence party consisting mainly of the wealthy, landowning section of Timorese society. This tentative government was “joined” by a third party, the Associacão Integraciacao de Timor Indonesia (APODETI), which—if the name wasn’t a giveaway—sought the integration of Timor-Leste into Indonesia.

The Indonesians watched these developments closely, as they presented an opportunity for further regional consolidation. The Indonesian Army undertook “Operation Komodo," which for the most part entailed funding APODETI’s activities and engaging in covert “pre-invasions” by the Indonesian military to make clear to the international community that, by hook or by crook, Timor-Leste would be integrated into Indonesia. Komodo bore fruit in 1975, when a whisper campaign alleging a planned seizure of government by communists (that old Indonesian enemy) caused the conservative UDT to relocate to Indonesia, where party leaders signed a petition supporting the integration of Timor-Leste into Indonesia. FRETILIN, knowing their days were numbered, rushed to form a single-party interim government without the input of the other major parties, as well as fend off attacks from UDT and Indonesian troops.

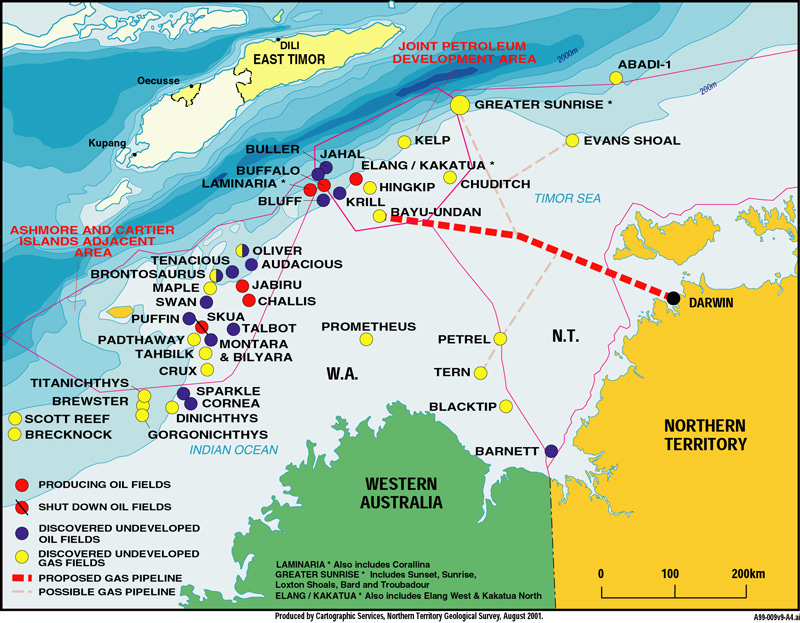

The Australian government was well aware of Indonesia’s intentions at this point and had received notice from the Indonesians of an impending attack on the Timorese village of Balibo. Australia refused to act, blaming the spectre of Vietnam for their quiescence. Realistically their reluctance was likely based on the vast oil and gas resources available in the Timor Gap, over which the Australian-Timorese Maritime border lay. Australia’s habit of using catastrophes in neighboring countries to further its own goals was never more cynical than their response to the invasion of Timor.

Gough Whitlam, Australia’s first Labor Prime minister since 1948, appeared publically to have a unique view of the imminent Indonesian occupation, contrasting Dutch and Portuguese colonial efforts negatively with the Indonesians’ apparent aspirations. While it would not necessarily have been wise for Australia to have involved itself in the Timorese situation militarily against a country as large as Indonesia, diplomatic means of mediation were clearly available. Whitlam instead sought to curry favour with the Indonesians at the expense of the Timorese people. Among the costs of his inaction was the death of 5 Australian journalists in Balibo on 16 October 1975.

Amid the early stages of Indonesia’s incursion, a farcical peace conference took place in Rome, where the Portuguese and Indonesian foreign minsters met to discuss the Timorese situation. No Timorese leaders were invited to these talks, which oddly enough did not lead to a cessation of hostilities. Indonesia invaded officially on December 7, 1975.

J. Patrick Fischer via Wikimedia Commons

The Indonesian army undertook a vast programme of ethnic cleansing following the invasion. This was familiar to observing colonial powers, consisting of massacres, systematic rapes, sexual slavery, forced adoption, the use of human shields, and the dispossession of land. The remaining FRETILIN forces retreated into the mountainous areas in the western part of the country. Australia, now having elected Liberal Prime Minister Malcolm Frazer, did its part and recognised the occupation as legitimate in 1978.

Indonesia had inherited a policy of Transmigrasi (transmigration) from the Dutch colonial authorities. Transmigrasi is essentially a form of gradual ethnic cleansing and ethnic colonization masked as shifting demographics in lightly-populated areas. Immigrants, predominantly of Javanese ethnicity, would be paid and provided land to settle in outer provinces like Irian and Sulawesi, so as to displace the majority ethnic groups in those areas.

Indonesian authorities applied this policy with gusto to Timor-Leste, importing Balinese and Javanese to the island to pick up the pieces following the devastating invasion. Transmigration was one of those all-around Bad Ideas that colonial powers formulate at arm’s length. While understandably detrimental to the natives of the settled islands, the Transmigrants themselves often left were worse off than before. Inadequate land preparation and planning left the Transmigrant settler farmers without income and often without food. Aside from the glaringly obvious human rights concerns, the cost of the policy itself was enormous with the costs of Transmigration taking priority over more relevant and important regional development projects in the outer islands.

The Timor-Leste conflict stagnated in the 1980s, and international recognition of the atrocities happening there slowly gained pace through the efforts of individual Timorese activists—in particular Jose Ramos Horta and Carlos Filipe Ximenes Belo, who eventually won the Nobel Peace Prize. The 1990s saw an uptick in rebel activity and the Santa Cruz massacre gained worldwide attention due to the presence of foreign media. Xanana Gusmão, then FRETILIN leader, was arrested and sentenced to life in prison, an action ignored by the international community at large that was nevertheless a galvanising force for the remaining FRETILIN faithful. During this time, Australian Prime Minsters Bob Hawke and Paul Keating ignored the ongoing massacres, with Keating dismissing one massacre as an “aberration” not to be taken as indicative of the situation at large.

(Source)

Following the death of Indonesian president and dictator Suharto in 1998, the Australian government found the inspiration to oppose the Timorese occupation. Specifically, it found that inspiration in the Timor Gap, the sea lane between the island of Timor and Australia, which just happened to contain the Greater Sunrise and Bayu-Undan gas and oil fields. Previously the Australians had secured a deal with the Indonesians allowing access to these resources. But a new, independent country would mean new maritime borders, which could potentially mean greater access to these lucrative fields for Australia. Prime Minister John Howard demanded that the Indonesians hold an independence referendum in Timor-Leste. Portuguese and Indonesian officials again held peace talks to discuss the issue, again with no Timorese representation. The Indonesians surprisingly complied with Australia’s demands, and the referendum saw independence win overwhelmingly. Pro-Indonesian militias immediately began inciting violence in the capital Dili, and United Nations election observers were forced to withdraw from the country.

After some wrangling by Australia, the United States, and the UN, the Indonesian government withdrew its forces and allowed an international peacekeeping force into the country ostensibly to deal with pro-Indonesia rebel groups. In 2002, this force handed control of the country to the new East Timorese government, under the leadership of Xanana Gusmão as president. Australia began negotiations immediately with the new government over the two countries’ maritime border in the Timor Gap. The Timorese had a dimmer view of Australian exploitation than did the Indonesians, and made clear that they were looking to cease most, if not all, Australian activity in the area. Importantly, the Australian government had withdrawn from the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea just 2 months prior to Timor-Leste’s independence, allowing it to avoid a binding vote at The Hague to mediate the dispute. Then-Australian Foreign Minister Alexander Downer led the negotiations for Canberra, which seemed to consist of Downer patronising the Timorese Government at large.

These negotiations hit a snag when it was revealed, by a whistle-blower known as “Witness K,” that Australia had bugged the Timorese government cabinet room, undertaken by the Australian spy agency ASIS. This action (unsurprisingly) led to a suspension of negotiations until 2018, when the border treaty was eventually finalised. The agreement followed UNCLOS guidelines in setting the boundary at the midway point between the two nations, rather than at the edge of Australia’s continental shelf (and therefore closer to East Timor), as Canberra had sought. The deal left East Timor in control of roughly 70 percent of the Timor Gap’s largest oil and gas field, Greater Sunrise, which it plans to begin exploiting in the next few years. Meanwhile, the trial of “Witness K” continues—the Australian government commenced legal action against that individual in 2018.

The specifics of why exactly colonialism is bad can often be nebulous or rooted in ideological concepts such as nativism, sectarianism or nationalism, but Timor-Leste is proof of the failings of colonialism on a practical human level. Indonesia as a newly independent country repeated the failures of the Dutch by attempting to complete the subjugation of their part of the archipelago. The Portuguese illustrated the callousness that former colonial masters show to their abandoned former subjects. And the Australians’ hypocritical and cynical exploitation of the invasion, occupation, and then independence of Timor-Leste showed the harm that middle powers enable larger global powers to carry out. Regardless of the intent, these actions towards and in response to colonial efforts were and continue to be to the sole detriment of the Timorese people.

Pat Honan has previously written for Challenge Magazine, works as a union official with United Voice, and lives in Darwin, Australia.

If Pat could write something up on the state of Australian politics/climate to follow up that Matt Brady podcast in the next couple months, that would be awesome. Local expertise adds a great element to the breadth that Derek provides daily.

Great write up. Learned about this from Radio War Nerd, but this article was not only very concise, but also did a great job showing the motivations of the Australians.