Columbus and the Islamic World

How the Age of Discovery affected the Ottoman Empire and beyond.

This essay is free to the public, but if you’re interested in reading more like it, along with nightly news updates on international affairs, analysis of US foreign policy, podcasts, and more, support Foreign Exchanges and subscribe today:

Happy Indigenous Peoples’ Day! As today is the anniversary of Christopher Columbus’s arrival in the “New World,” I thought it appropriate to examine his impact on the Old World—specifically on the part of the Old World controlled by Muslim powers in 1492. I wrote this essay many years ago at my previous website based on notes from various grad school lectures, and have since rewritten and beefed it up a bit with some additional material.

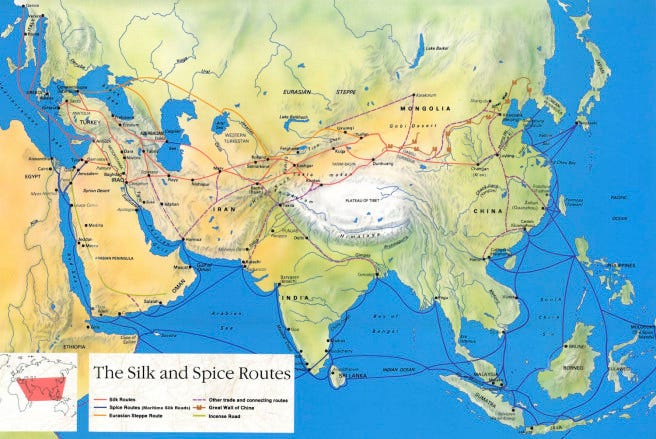

Europeans had been trading with the “Far East” for centuries before the advent of Islam. Ancient Roman luxuries have been found at ancient Chinese sites, for example, and vice versa. Of more importance to Rome than its trade with China was its trade with India, via the Red Sea and Egypt (or, if you’re inclined to believe early Muslim historians, via a massive yet somehow mostly unnoticed international trade hub at Mecca).

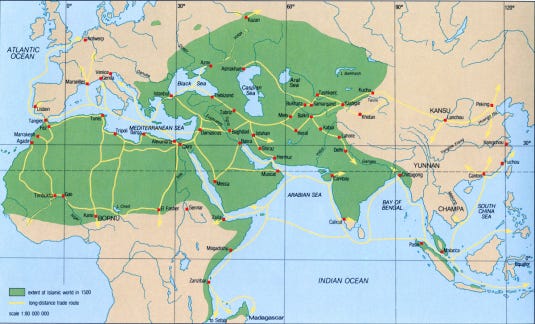

The arrival of Islam, and with it a brand new empire stretching all the way from Iberia to India, didn’t really complicate those trade routes too much. In terms of overland trade the caliphate simply stepped in where the various Persian empires had been, and while the loss of Egypt hurt the Roman (or Byzantine, if you prefer) Empire, there was too much money to be made for the new Arab/Muslim bosses to just shut that Red Sea trade down. This state of affairs continued for centuries, with the caliphate and the Byzantines, and briefly the Latin Crusaders, in a state of almost perpetual war, but usually prepared to keep trade routes open in order to make some scratch. My point is that the commercial relationship between Europe and “the Orient” was already millennia old by the 15th century.

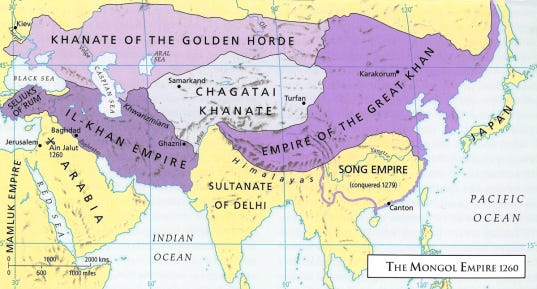

Then along came the Mongols in the 13th century, eliminating the caliphate altogether and creating a network of Mongolian khanates stretching from Eastern Europe to China and Korea. If you count those khanates as one entity (which is problematic given the level of infighting between them, but not completely inaccurate), it was the greatest contiguous land empire (by “contiguous land empire,” I basically mean “leave the British Empire out of this”) the world has ever seen.

These khanates (like the Ilkhanate in Persia/Iraq and the Golden Horde on the Russian steppes) rarely got along with one another. But if there was one thing the Mongols loved more than fighting and conquering it was trading and making money, so they made sure that it was mostly smooth going for overland traders on the East-West “silk road” (or roads, since there were actually a few different routes). Having most of Eurasia under Mongolian control actually made traveling far easier, since not only was security pretty tight but merchants could also do helpful things like depositing their hard currency at one end of the empire in exchange for paper banknotes (obviously a lot easier to lug around than coins) that were redeemable wherever the Mongols were in control—which was almost everywhere, except for India.

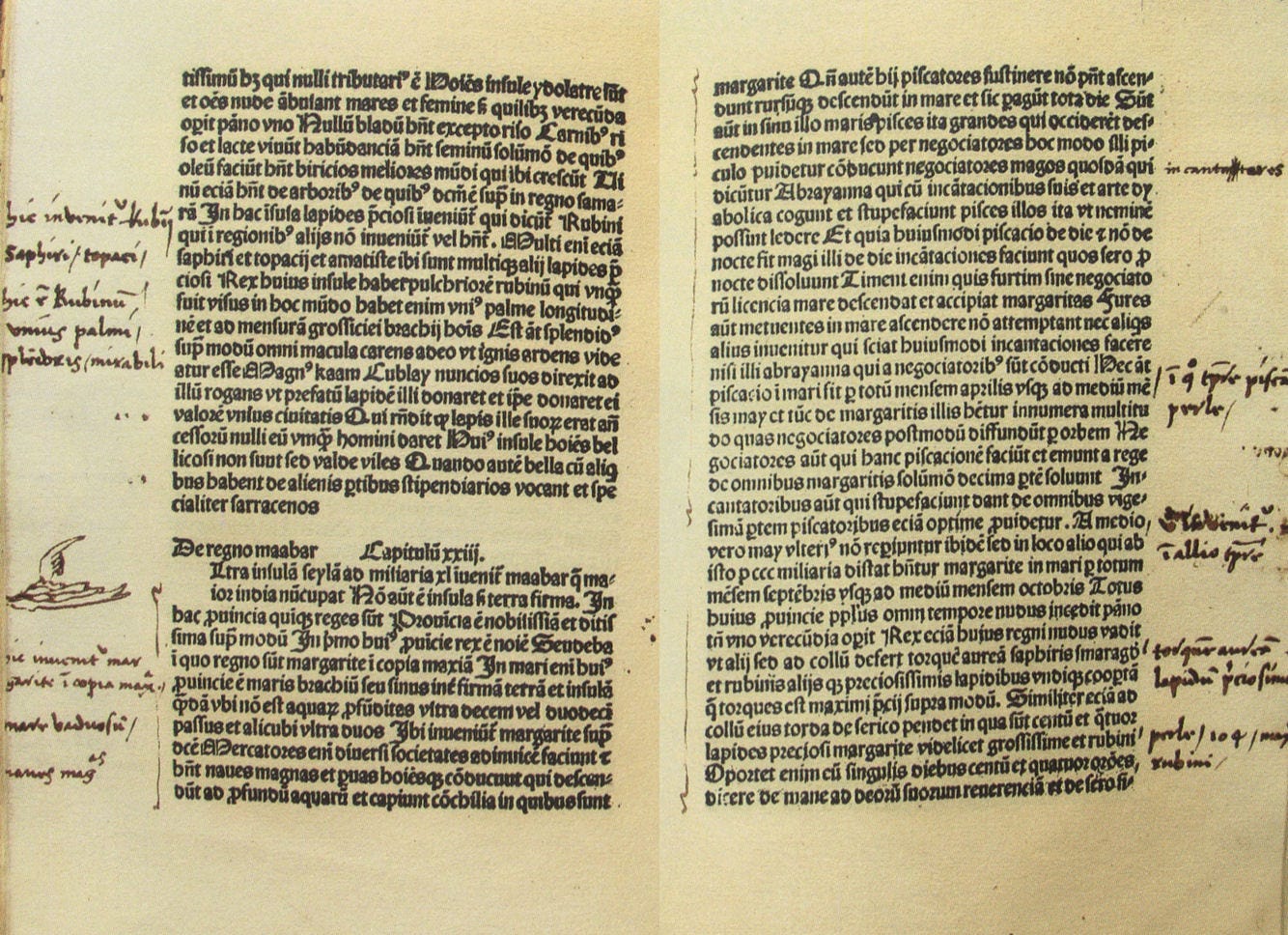

It’s in the Mongol period that we hear of European travelers—missionary-diplomats like William of Rubruck and Giovanni da Pian del Carpine, or merchants like Marco Polo and company—making the overland trek from Christian Europe all the way to Mongolia or China. The Mongols never conquered Egypt, which by this point was under the control of the Mamluk dynasty, but the Mamluks also were keen to keep trade routes to Europe open. In fact, their whole sultanate depended on it—both on the commercial sea routes through the Red Sea to India and on the north-south slave trade. The Arabic word mamluk means “owned,” or when applied to people “slave,” and the Mamluk political hierarchy was perpetuated by the succession of slave soldiers to high office and on to the throne. Those slaves were usually purchased from the Eurasian steppe and/or the Caucasus, mostly via European traders.

As it happens, the Mongols were better at conquering than they were at ruling, and their various khanates in the Middle East and across Eurasia were already breaking apart and collapsing around a century after they’d been established (the Black Death and some unwelcome environmental changes didn’t help). That breakdown brought with it a lot of unwelcome insecurity for traders along the Silk Roads, who were frequently beset by thieves and marauders. The plague contributed to the loss of Eurasian cohesion as well, both for its direct effects and the contributions it made to breaking apart the “Pax Mongolica.” The hope of a unified trans-Eurasian empire was briefly revived by Timur in the late 14th century, when his campaigns reunified the Ilkhanate, extended his empire’s reach into India and Central Asia, decimated the Golden Horde (taking out their competing, more northernly, Silk Road route in the process, probably by design), and crushed (temporarily) the nascent Ottoman Empire that had been harassing what was left of the Byzantine Empire.

Timur, like any good Mongolian conqueror, liked to make money, so he restored trade routes and promised safe travel to merchants on his territory. Unfortunately for the merchants, Timur died on his way to conquer China in 1405, and while his son and successor, Shahrukh, was a better Muslim than Timur had been, he wasn’t nearly as good a conqueror. The empire Timur (re)built started losing territory very soon after he died, and really began to fall apart when Shahrukh died in 1447.

The biggest beneficiary of Timur’s death was the aforementioned Ottoman Empire. The Ottomans were thrown into an interregnum/civil war after losing the Battle of Ankara to Timur, but once that was over they quickly rebuilt their former strength and then some. The empire grew to absorb most of Anatolia and the Balkans, and finally ended the Roman/Byzantine Empire in 1453 when its army captured Constantinople. The Ottomans, who now controlled the western terminus of the Silk Road (we’re basically down to one Silk Road at this point, since Timur put an end to the northern route), were pretty fond of money as well, so they weren’t really a threat to close down trade with Europe. However, they had also just conquered the most important city in Christendom and were a clear threat to march right into the heart of Europe.

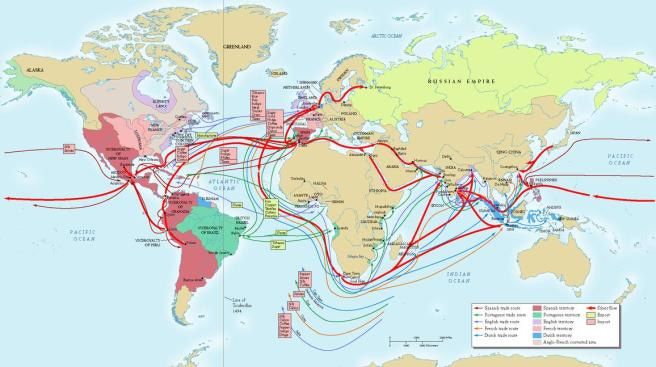

The Ottomans also became serious naval player in the eastern Mediterranean, something no Islamic entity—Arab, Mongolian, or otherwise—had ever done before. This meant that European merchants (Venetians, primarily) no longer necessarily controlled maritime shipping lanes. Venice was the dominant European player in the eastern Mediterranean, which meant that European merchants looking to trade with lands to the east usually had to contract with Venetian shippers on relatively unfavorable terms. Meanwhile, Muslim Iberia was in the process of falling (or reverting, if you prefer) to the Christians, creating new Christian kingdoms at the far edge of the Mediterranean who were very well-placed to consider, say, sailing around Africa to open trade routes to the East that didn’t cross any Muslim territory. The fact that the new Iberian kingdoms were all competing with one another only raised the stakes in that game. Their exploratory voyages had started even before the Ottomans took Constantinople, with Portugal exploring the African coast in the 14th century in order to bypass the Trans-Saharan trade routes and access West Africa’s abundant gold and slave wealth directly.

The year 1492 is notable not only for Columbus’s voyage, but for being the year when the last Muslim kingdom in Iberia (Granada) fell to the armies of Ferdinand and Isabella, whose marriage had united the kingdoms of Aragon and Castile and laid the foundation for modern Spain. The Ottomans were still ascending, having crushed the Aqqoyunlu confederation in 1473 (which had made diplomatic overtures to Venice about attacking the Ottomans jointly), and wouldn’t be seriously challenged until the rise of the Safavid Dynasty in Iran in 1501 (and even that challenge was one they would effectively put down by 1514).

By 1517, the Ottomans had defeated and absorbed the Mamluk Sultanate, gaining control of the Red Sea trade route in addition to the Silk Road—this only added urgency to the European search for alternatives. With the “around Africa” route increasingly the purview of Portuguese sailors, who would get to India that way by the end of the 15th century, the Spanish monarchs were naturally intrigued by the idea that someone could sail across the ocean to the west and wind up in China, bypassing both the Ottomans and the Portuguese. This route hadn’t been tried before because most learned people—correctly, as it happens—thought that the world was far too large for such a journey to be possible.

Enter Columbus. If you’re still laboring under the idea that Columbus boldly challenged the prevailing contemporary wisdom that the world was flat and ultimately proved himself right, you should know that this pleasant tale is completely fictional. Europeans had understood that the Earth was spheroid since ancient times. Columbus did challenge prevailing wisdom, in that he was convinced that the world was far smaller than was generally believed. He proposed that making a western trip to the “Far East” was well within the range of contemporary sailing vessels. He was completely wrong, and prevailing wisdom about the size of the planet was surprisingly close to correct. Had the Americas not been in the way, Columbus and his crew would almost certainly have starved to death before they got anywhere near East Asia.

Of course, in 1492 I suppose there was enough uncertainty about the size of the Earth that a guy like Columbus could get a hearing at court—one court, at least. Whether he was an especially persuasive pitch-man or was the kind of guy a wealthy ruler would have been willing to pay to go away for a very long time, his appeal got the proto-Spanish monarchy’s attention. With the Muslims finally removed from the peninsula, Ferdinand and Isabella (mostly Isabella) decided to embrace Columbus’s math in order to best Portugal’s commercial strength. And possibly also because they wanted him to go away. Based on some of the historical accounts of Columbus’s later behavior, I don’t think we can discount that as a motive.

The Ottomans felt the effects of the discovery of the Americas, at least to some degree. For most of the 16th century and into the 17th century Europe was hit by something called the “price revolution,” which was essentially a massive (by 16th century standards) inflationary trend. Historians used to believe that it was the influx of large amounts of silver (especially) and gold from the Americas that devalued currencies all over Europe and caused this inflation, but nowadays scholars believe it was more complicated than that. It’s suggested that the bigger culprit was that Europe’s population finally started expanding again—after remaining stagnant for decades following the Black Death—and also rapidly began to urbanize. I’m not an economist, so I can’t give you a detailed explanation here, but the upshot as I understand it is that all these new people and all that urbanization increased the demand and/or velocity of money, and that’s what started the inflationary trend. At any rate, I think most of those scholars still agree that the influx of American silver contributed to the price revolution, even if it wasn’t the main cause.

The Ottomans suffered a severe economic downturn in this period. A steady stream of imperial surpluses became a steady stream of imperial deficits starting around the late 16th century. Turkish historian Şevket Pamuk’s research estimates that prices in Istanbul rose around 500% between the end of the 15th century and the start of the 18th. The main Ottoman silver coin, the akçe, went through a major debasement in around 1585, which (according to Pamuk) was the main driver of the inflationary trend, but he notes that this debasement was itself brought on in part by the economic strain of the price revolution. The fact that European trade with India no longer relied on either of the two routes the Ottomans controlled probably contributed as well.

Where the traditional view was that the Ottomans were uniquely hard hit in the 16th and 17th centuries, contemporary scholars argue instead that their downturn was more or less in keeping with the trend in Europe and maybe with a trend that swept the whole world. There’s a term for this, thanks to Eric Hobsbawm: “The General Crisis (of the 17th Century).” It’s far from a historical consensus, but the argument goes that for a host of reasons unrelated to New World precious metals, governments and societies across Eurasia hit a proverbial brick wall. Europe was wracked by wars and civil wars involving, for example, England, France, the Holy Roman Empire, the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, and the Spanish Empire (the “Thirty Years’ War” encompasses a lot of this, though not all of it). Japan was wracked with agricultural struggles and several peasant uprisings. The Ming Dynasty collapsed in China.

Among historians who agree with the General Crisis theory, one of the most common explanations involves a period of global cooling that reversed the post-Black Death population growth and actually caused (especially when you couple it with all of those wars) a substantial population decline. That population growth, if you recall from above, had contributed to the runaway inflation of the price revolution, and the sense you get here is of a lot of shocks happening one on top of the other until systems start to break down under the strain.

There were other causes for the Ottoman economic crisis, specifically wars with the Safavids and Habsburgs, a major slowdown in the empire’s pace of territorial expansion, and a change in land management from productive hereditary land grants (which encouraged landlords to manage their grants for long-term productivity) to destructive tax-farming (which encouraged bidders to extract as much money as they could, as quickly as they could, from a parcel of land before it was taken away from them). Pamuk’s work incorporates these other factors and shows that the impact of the new American silver on the Ottoman economy was more limited than previously believed. He’s also shown that the by the early 18th century the Ottoman economy was probably back on solid ground, though whether it ever completely recovered from the shock remains a matter of some conjecture.

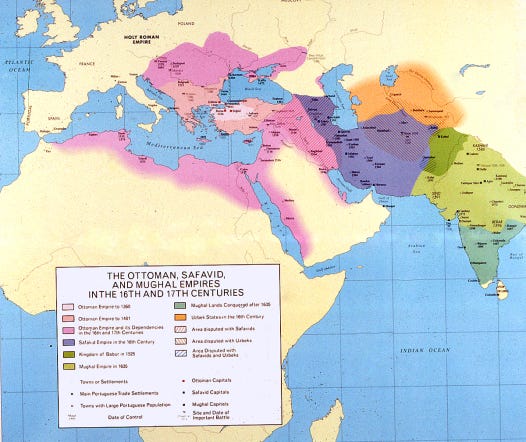

In case you’re interested, elsewhere in the Islamic world in this period things weren’t quite so difficult. The 16th-18th century period is known as the age of the “gunpowder empires” because the Islamic world was dominated by three large imperial units—the Ottomans, the Safavids in “Greater Iran” (Iran plus some of the Caucasus plus most of Afghanistan plus occasionally Iraq), and the Mughals in modern (northern) India and Pakistan—whose militaries were all organized to one extent or another around, you guessed it, gunpowder weapons.

The Mughal economy thrived in this period (and in general for much of that dynasty’s lifespan), owing mostly to the fact that India, along with China, was one of the two great eastern terminal points for European trade. It’s estimated that India’s economic output at this time accounted for slightly over a fifth of the world’s total economic output (by comparison, the US and China each top out at around 16% of total global GDP nowadays), and because its goods were so highly prized in foreign markets it tended to accumulate precious metals/specie rather than having to spend it, so it wasn’t affected by price shocks the way the Ottomans were. If anything, the arrival of Europeans in the Indian Ocean via the African route only increased the demand for and trade in Indian goods, and the arrival of New World silver increased Europe’s ability to pay for them, all good things for India’s economy.

The Mughals also benefited in the 16th-17th century from a series of capable rulers, from Akbar (r. 1556-1605) to Jahangir (r. 1605-1627) to Shah Jahan (r. 1627-1658). Though whether their effectiveness helped strengthen the empire or the empire’s strength is the reason we think of them as “effective” today is one of those chicken-and-egg questions that probably can’t be resolved.

The Safavids were comparatively poorer than either the Mughals or the Ottomans, and had only one truly important product to offer the world market: silk, the production of which may have come to Iran from China via our friends the Mongols. The Safavids actually had a very productive run from the late 1500s through the early 1600s, partly because of European exploration and Ottoman struggles. The arrival of European traders in India via the passage around Africa meant that the Safavids no longer needed to rely on overland trade to Europe via the Ottomans, with whom they were frequently at war. Instead, they could ship their silk via the Mughals, with whom they had generally good relations until the mid-17th century, to European traders in India. At the same time, Ottoman economic weakness forced the empire to give the overland Safavid silk trade (usually conducted by Armenian merchants) fair treatment even when the Ottomans and Safavids were at war.

Like the Mughals, the Safavids also benefited from strong political leadership in this period, in the person of Shah Abbas I (r. 1588-1629), the dynasty’s only truly great monarch—though the same chicken-and-egg question we asked of the Mughals applies to him as well. Once he died, the drop off was precipitous, and not only did relations with the Mughals decline, but as the 17th century wore on European merchants grew tired of dealing with the Safavids and began to fill their silk needs elsewhere.

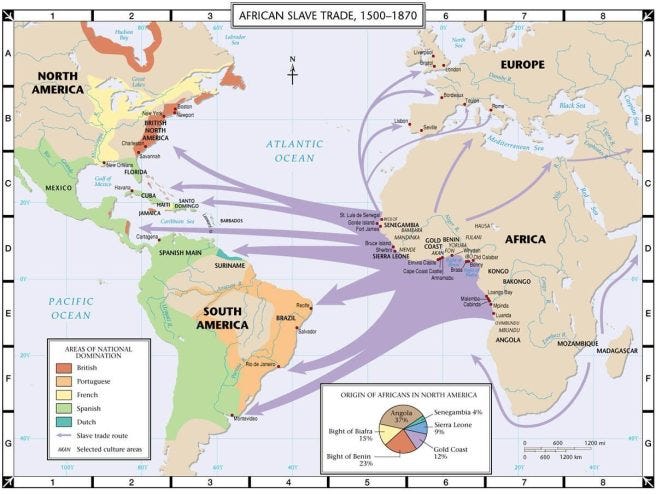

One final word, and it’s about the slave trade.

It’s easy to lose sight of this when you’re talking in benign terms about “trade routes” and economics and inflation, but so much of this economic system was underpinned by the trade in human beings that it’s irresponsible not to at least point that out. The slave trade was as much a north-south trade as east-west, with Circassian and Central Asian slaves finding their way south to Mamluk and later Ottoman Egypt, while African slaves were traded across the Sahara to North African principalities and beyond, in addition to being taken to the Americas. The transatlantic slave trade is really beyond our purview here, but the trans-saharan trade, and the slave trade in the Balkans, Caucasus, and Central Asia, is crucial.

The gunpowder empires depended on enslavement, with the Ottomans conscripting sons from Christian families in the Balkans to serve at court and in the army/Janissary Corps, and the Safavids taking slave soldiers from Christian kingdoms in the Caucasus (in an effort to mimic the Janissaries). The Mughals likewise enslaved non-Muslim Indians (mostly Hindus, obviously), selling some abroad, and also traded for slave soldiers from Central Asia.

The Ottomans also dealt in African slaves, though usually for more menial farming and household duties. African eunuchs in the imperial palace could rise to positions of great influence at court—the Kızlar Agha (“chief of the girls”), who ran the palace harem and was frequently one of the two or three most powerful people in the Ottoman court, was usually African. This is why you’ll sometimes see that position described as the “chief black eunuch.” Yes, there was a “chief white eunuch,” the Kapı Agha, who oversaw the gate between the inner and outer Ottoman courts and thus controlled outside access to the sultan. This was a very powerful position, but later in Ottoman history—when the harem became the most influential part of the palace—it was eclipsed by the Kızlar Agha. In general, however, African slaves were treated worse in the empire than European slaves. Slaves in some of these systems could expect eventual manumission and even a pathway to high office, and in that sense had an experience that could be quite a bit different from slaves in the Americas. But those factors shouldn’t detract from the general ugliness of the system.